On the 20th anniversary of the Rwandan genocide, University of Minnesota students and faculty are exploring ways to avoid future tragedies.

The Humphrey School of Public Affairs, in addition to the University’s Human Rights Program and Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, hosted a conference last week in honor of the genocide’s anniversary. Researchers shared their new ideas, and international leaders discussed the importance of knowing the root of the catastrophe.

“I think the more students have an understanding of and appreciation of those issues, the better equipped they’ll be to deal with them,” said Humphrey School Dean Eric Schwartz.

Research on genocide prevention is relatively new, but knowing more could help prevent them.

“The more that we understand about the causes of the genocide in Rwanda, the more we’ll be able to prevent other genocides,” said Barbara Frey, who directs the University’s Human Rights Program.

While there’s existing research that focuses on prevention measures and the aftermath of the tragedies, there’s still a need for consolidating the studies and finding predictable patterns.

“Through research, we can learn more about why [genocide] happens and then be better ready to respond to it,” sociology Ph.D. candidate Hollie Nyseth Brehm said.

Nyseth is studying the causes of genocide for her dissertation. Until this point, Brehm said, many previous scholars didn’t study the warning signs of genocide.

In her research, Brehm said she found that international leaders often disagree on how they should intervene, which complicates the issue and delays peace.

For example, Brehm said some leaders use military power, while others prefer enacting economic sanctions.

The Rwandan genocide began on April 6, 1994, when tension between Hutu and Tutsi groups peaked. It lasted until mid-July, when the Tutsi rebel group, the Rwandan Patriotic Front, overthrew the Hutu regime.

Nearly 14 percent of the country’s population died during the genocide.

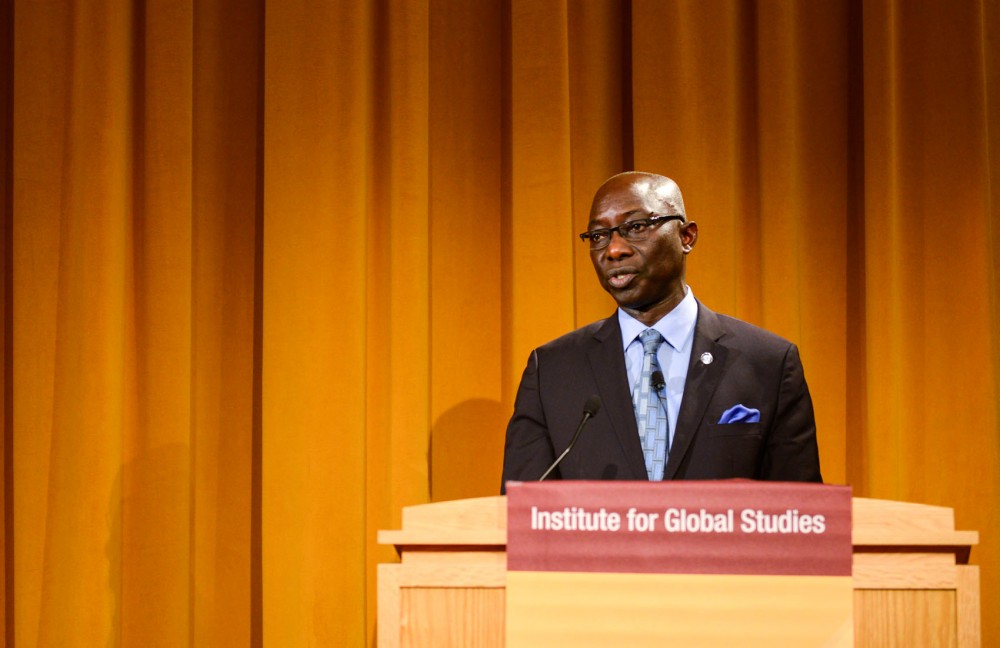

Adama Dieng, who is the special adviser on the prevention of genocide for the United Nations, spoke at the conference Wednesday. He said it’s important to understand the root of why the tragedy occurred, citing long-term discrimination and hate-speech.

“To have close to a million people murdered within 100 days, we have to be sure we remember what happened,” said Gregory Gordon, director for the Center for Human Rights and Genocide Studies at the University of North Dakota. Gordon was a panelist at the event.

The three-day conference also included elementary through college educator training, in which teachers learned from University faculty members about how to create effective lessons about genocide.

Learning about Rwanda can help students understand other complex situations that involve human rights violations, Schwartz said.

Frey echoed him, saying the conference sparked discussion on how to overcome human rights violations in the present.

Now Rwanda is arguably a safe state, Frey said, noting criticism surrounding its authoritarian government and the general consensus that learning from the past will help prevent future genocides.

It takes a shared effort worldwide to prevent a genocide, Gordon said, which stems from awareness and education on the issue.

“If anything good can come from that in terms of lessons learned, then that’s the only silver lining that there could be,” Gordon said.