From electronics to tableware, plastic is everywhere and varies by shape and size.

Despite plastic-made products’ differences, most share a common origin as fossil fuels drilled out of the ground.

Now, equipped with a recently awarded federal grant, University of Minnesota researchers are working to even the playing field between traditional plastics and more environmentally friendly alternatives.

The University’s Center for Sustainable Polymers received the five-year, $20 million grant from the National Science Foundation last month to research disposable, non-toxic plastics created from renewable resources.

CSP director Marc Hillmyer said the center will provide initial research that will make sustainable plastics more competitive on the market alongside their petrochemical cousins.

“We are working more on the front end of this effort,” he said. “We are laying the basic research foundations to allow technologies to ultimately be translated in the marketplace.”

Normally petroleum products, such as oil and natural gas, are refined into large molecular building blocks called polymers, from which plastics are then processed, Hillmyer said.

CSP researchers instead want to source the same chemicals from plant-based materials, like sugars, carbohydrates and vegetable oils, Hillmyer said.

But new plastics, he said, must also match the quality of current ones at a comparable cost in order to succeed.

Department of Chemistry Chair and CSP researcher William Tolman envisions a cyclical future for sustainable plastics.

“You start with plants, and you take some plant-based feedstock, convert it into some kind of plastic [and] use it for something like a yogurt container,” Tolman said. “At the end of its life cycle, it gets tossed into a composting pile and gets converted back.”

Hillmyer said researchers eventually hope to convert waste biomass into plastics — though he said that development is a ways off.

In the meantime, some petroleum-based plastics can pollute the environment for generations, Tolman said.

“Once they’re done being used, they basically don’t degrade for 10,000 years,” he said. “We’re trying to develop replacements and new types of polymers that are derived from renewable resources and ultimately are also biodegradable.”

Kathleen Schuler, a program director from statewide nonprofit Conservation Minnesota, said her group’s efforts to promote non-toxic products aligns with the center’s mission.

“Plastics are a huge problem,” she said. “Moving away from petrochemicals reduces the impact on the climate, and that’s one of the principles of green chemistry.”

‘High-risk, high-reward’ research

Beyond informing the public about green chemistry, CSP also gives students a chance to work in an environment where discoveries are building toward future breakthroughs.

“Students can understand and see how the fundamental science they’re doing can have a real impact on environmental stewardship, sustainability and real applications,” Tolman said.

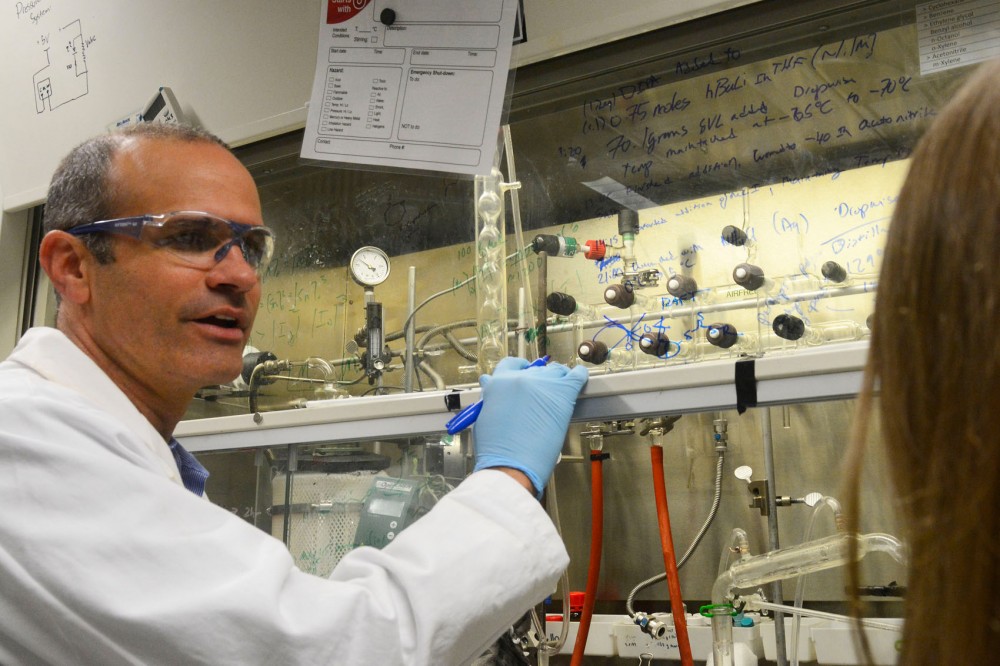

Upwards of two dozen University graduate students and postdoctoral researchers will toil away at the center this year, focusing on topics like feedstock conversion and hybrid materials, Hillmyer said.

“It’s just a good opportunity to work on high-risk projects we might not normally get funding for,” said Debbie Schneiderman, a materials chemistry doctoral student. “High risk, high reward, hopefully.”

Schneiderman added that plastics need to become more renewable, and she said CSP director Hillmyer has the energy to guide the center’s research in that direction.

Despite the increased national funding, research at the center remains highly competitive, Hillmyer said.

“All the senior investigators in the center vie for these funds by writing proposals. … We use those proposals to rank the ideas we want to support,” Hillmyer said. “There are more ideas coming from the Center for Sustainable Polymers than we can fund.”

Currently, more than 40 projects are already up and running at the center, he said.

“Basic research is a long-term endeavor,” Hillmyer said. “At the end, we hope to have generated the knowledge that is needed to take this field to the nextlevel.”

Garnering support around the nation

Under the CSP’s umbrella, scientists from the University are joined by partners from Cornell University, the University of California-Berkeley and more than 30 companies nationwide.

But when it launched in 2009, the University had to help get the center off the ground using start-up money.

In 2011, the University attracted an initial three-year $1.5 million grant from the NSF, which acted as a trial run for additional backing, Hillmyer said.

Last year, CSP competed in a vigorous review process to receive a second stage of funding, said Katharine Covert, a program director from the NSF’s chemistry division.

Researchers flew to Washington, D.C., to pitch their cases, and a panel of 15 national and international experts reviewed proposals from a number of candidate centers, she said.

Ultimately, CSP came out on top.

“We made a happy phone call to Minnesota,” Covert said, adding that the center’s commitment to forging ties with industry gave it an edge. “They are going to be leaders in the field.”

The grant establishes CSP as one of eight Centers for Chemical Innovation, all of which Covert oversees, to perform groundbreaking research with the NSF’s support.

“In all of our programs, we start with funding great science,” Covert said. “It’s great chemistry with great societal impact.”