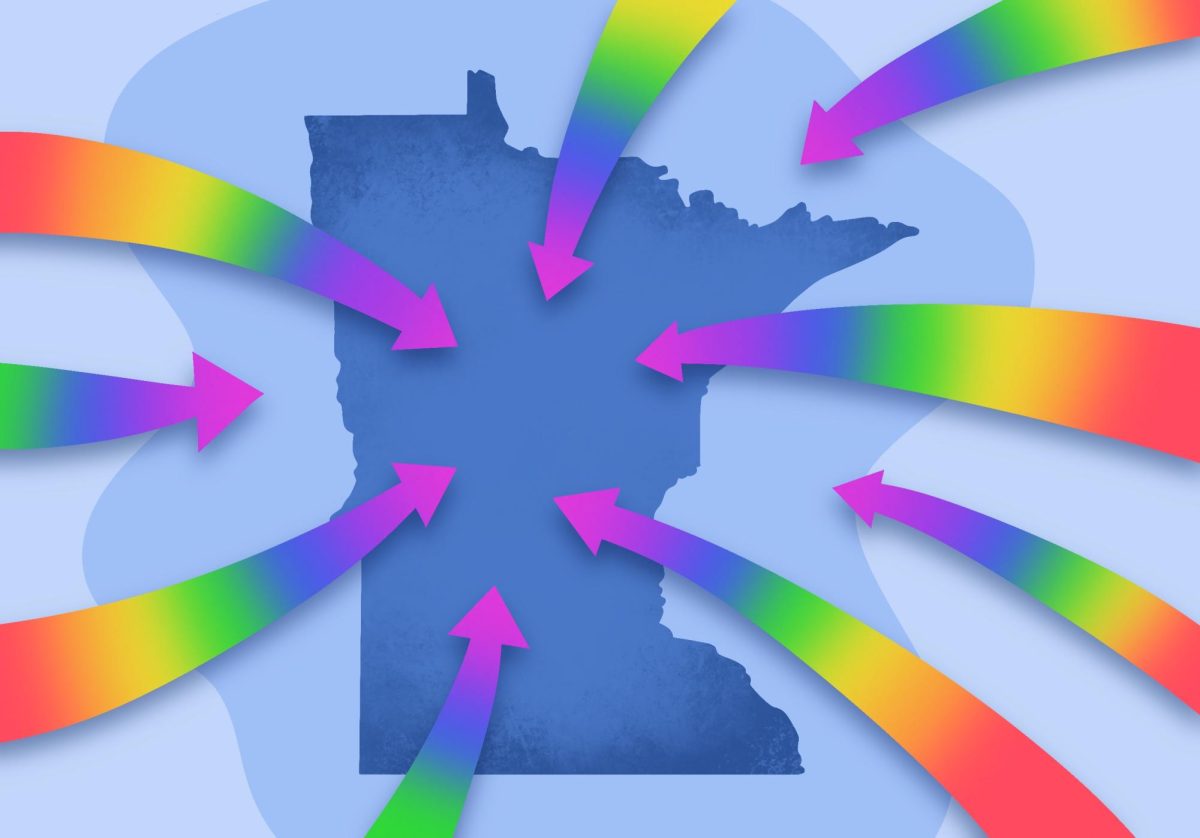

A University of Minnesota research program is looking to increase discussion about the opioid epidemic in underrepresented communities throughout Minnesota.

The program aims to reduce stigma around the opioid crisis, especially in communities of color, according to the research report. After communities participated in opioid surveys, researchers then presented their data back to the communities. Now they’re aiming to collect 10,000 more survey responses from additional communities in Minnesota.

“We’re doing [this] because we think that it’s degrading to have stigma around opioids and that further disadvantages people in communities of color who are hoping to address and overcome the challenges of opioids,” said Karen Monsen, a researcher and professor at the University’s School of Nursing.

Researchers want to instead focus on the strengths in these communities, she said.

The program began with outreach to 13 different communities around Minnesota to try to get a sense of what was happening, Monsen said.

From presentations to focus groups, they found a common theme — adverse feelings toward opioid use.

Communities have seen the dangers of opioids, and they’re looking for alternative solutions, Monsen said.

Different communities heard about the program and wanted to be involved, said Robin Austin, a researcher and assistant professor in the University’s School of Nursing.

“A lot of times we were there just to listen,” she said.

Community partners from Hue-MAN Partnership, Parents in Community Action, the Hawthorne Neighborhood Council and Minnesota Head Start Association connected communities to the research program.

“Knowing the history of how other epidemics have been described for our communities, we decided we needed to have our own narrative,” said Clarence Jones, the community engagement liaison for Hue-MAN.

For many communities of color, opioid issues are often considered normal, he said. They don’t realize they’re apart of the epidemic.

“In our community we don’t talk about opioids, we talk about heroin and OxyContin,” Jones said.

The MyStrengths MyHealth application involved in this program was created to keep the terminology simple and accessible to the general public, Monsen said.

“This was prevalent on both sides. The medical field didn’t describe it for us, and we didn’t describe it like that,” Jones said.

Many people are impacted by the epidemic and they don’t even know, he said.

“People go to the doctor, they get these pills and pretty soon they become addicted,” Jones said. “…So when they can’t get those pills, then they go to other drugs.”

Another problem they’re trying to change is the history of distrust between the University and communities of color, he said.

University researchers were good partners on this project and involved communities in every aspect of it like they should, Jones said.

“What we realized is that the conversation about opioids wasn’t being had in our community because we weren’t being included in the conversation,” said Samuel Simmons, a member of Hue-MAN. “How do you have a conversation with a community that hasn’t been included?”

Communities of color often remembered the mistreatment and lack of compassion they received during the crack epidemic, he said.

“There were times where professionals would say, ‘Why do they keep bringing that up?’” Simmons said. “Because it still has an effect on the community to this day.”

However, these surveys are helping start conversations, he said.

“We can talk about disparities, which we often do, but sometimes that disparity is actually even made larger for the lack of conversation. A lack of being a part of the conversation. And a lack of effort on the part of the individuals who have the information,” Simmons said.

Communities are learning what to look for, he said.

“Building on a relationship we already had with the University made it easier,” Simmons said.