Three weeks after the birth of her first child, Austin Calhoun returned to work, shut her office door and cried.

Three weeks after the birth of her first child, Austin Calhoun returned to work, shut her office door and cried.

Calhoun took the two weeks paid parental leave guaranteed to her as a University of Minnesota academic employee, plus a week of vacation when her wife gave birth to their son.

“Any parent will tell you that’s not enough time to support your partner in this complicated … stressful, anxiety-inducing, wonderful time,” Calhoun, chief of staff in the Office of Medical Education, said.

On Friday, the University Academic Professionals and Administrators Senate unanimously passed a resolution requesting the University provide equal amounts of paid leave to adoptive and birth parents. This push is the most recent effort from several University groups that have been encouraging reform of the school’s leave policies.

Organizations representing University employees, faculty and graduate students have been working to fix various aspects of parental leave policies, from perceived inequities to giving new parents the option to take a temporary leave.

The efforts come amid an increased focus on parental leave. At the University of Michigan, graduate students are working for a new leave agreement, and at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, faculty members and employees have requested improved policies, even after the recent implementation of a modified duties policy.

Seeking parental equity

After unanimously approving a resolution pushing the University to give all parents at least six weeks paid leave after the birth or adoption of a new child last week, the P&A Senate is awaiting a formal response from University administrators.

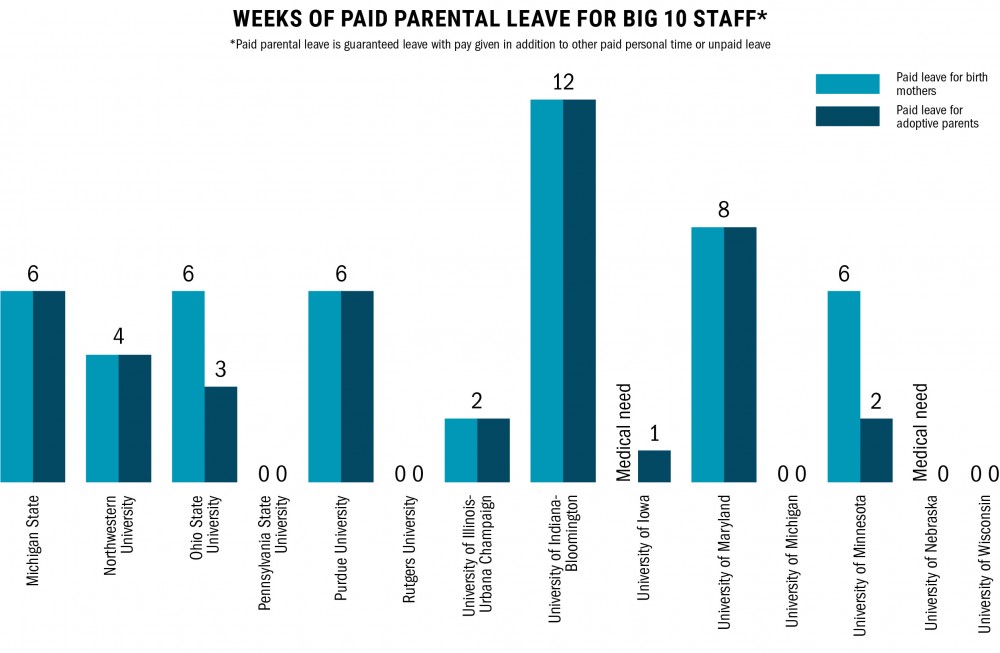

Under the current policy, adoptive parents are allowed two weeks paid and four weeks unpaid leave. Female employees who give birth receive six weeks paid leave.

Besides Ohio State University, the University of Iowa, the University of Nebraska and Minnesota , all other Big Ten schools offer birth and adoptive parents the same amount of paid leave.

The Parental Equity Resolution outlines several P&A concerns about the discrepancy in paid time off for birth and non-birth parents. It states that adoptive parents often need more than two weeks to bring a child home, adding that same-sex couples are disadvantaged by the policy.

It also says licensed daycare centers rarely accept kids younger than six weeks old.

The University’s Office of Human Resources, which is responsible for the parental leave policy, declined to comment. A University spokesman also didn’t make an administrator available for an interview.

According to a 2013 report from the Williams Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Law, same-sex couples are four times more likely to raise adopted children than heterosexual couples.

This puts same-sex couples at a disadvantage under the current policy, said Ian Ringgenberg, a P&A senator who helped write the resolution.

P&A Senator Steven Shore and his wife are waiting to be matched with a child to adopt. Once a match is found, they will travel to meet the birth mother and fill out paperwork, which normally takes two weeks, Shore said.

“There’s my two weeks [paid leave] right there, waiting for paperwork and not really bonding with the baby,” he said.

Calhoun, a P&A Consultative Committee member, has taken leave both as a non-gestational parent and as a birth mom. She took two weeks paid leave plus a week of vacation in 2013 when her wife gave birth to their first son and six weeks paid leave when she gave birth to twins in 2015.

The policy doesn’t allow sufficient time off, she said. A parent shouldn’t be denied leave just because they aren’t physically recovering from birth, Calhoun said.

“Our current policy really makes assumptions about what … family structure looks like,” Ringgenberg said. “The idea of parental leave isn’t [just] to recover physically from giving birth. It’s to bond with the family.”

The P&A Consultative Committee is also mulling another parental leave resolution passed in January 2016. The proposal has been shelved by the P&A Senate for now, Riggenberg said.

This resolution requests the University administration “investigate the possibility of increasing paid parental leave,” citing a number of large Minnesota corporations like 3M and Wells Fargo that offer more than six weeks paid leave.

“We’re trying to be pretty realistic in dealing with the most egregious circumstances right now,” he said.

Graduate students are also mobilizing to reform the same parental leave policy. Last October, the University’s Council of Graduate Students passed a resolution requesting equal amounts of leave for employees of all genders.

Currently, the policy says females may take six weeks paid leave while males are eligible for two weeks leave.

Modified duties

Three years ago, the Women’s Faculty Cabinet began drafting a policy to give tenured and tenure-track faculty time to care for a new child and continue professional activities by temporarily reducing their teaching responsibilities.

The policy was approved by the provosts and about to be implemented when University faculty filed to unionize in early 2016. As a result, a status quo order was put in place, meaning faculty working conditions can’t be changed until the vote takes place, said Jeannine Cavender-Bares, WFC senior co-chair.

However, deans and department heads have always had the discretion to grant modified duties for parents who ask because there aren’t rules prohibiting it, but a lack of official policy means managers are free to deny these requests, she said.

“It’s super frustrating because what’s happened is different colleges are implementing it,” Cavender-Bares said. “It’s not uniform. Some deans don’t see any need for it and others really see the value.”

The WFC is working to increase awareness of this option, as many faculty members, department heads and deans aren’t aware of it. In March, the Women’s Faculty Cabinet presented the unofficial policy to a University governance committee.

Additionally, the group will host a dean’s panel in May that will include discussion of the proposal and parental leave, Cavender-Bares said.

“[New parenthood] is a make-or-break point for a lot of academics. That is a bottleneck point where academics fall through the cracks,” she said, adding that many faculty members hit professional roadblocks, like not achieving tenure, when they become parents.

In fall 2016, veterinary medicine assistant professor Meggan Craft took a modified duties semester following the birth of her child. She said the arrangement eased the transition from leave to full-time work.

The exhaustion of being a new parent probably would have negatively impacted Craft’s teaching and research if she hadn’t been granted the temporary teaching release, she said.

“It allowed me to just focus on advising my grad students and my postdocs and my research … while dealing with the demands of parenting,” she said.

In the Big Ten, other faculty have also taken family policy into their own hands. At the University of Wisconsin in 2013, female faculty members developed a policy allowing them to use paid sick hours to take temporary leaves from teaching to care for a new child because the school doesn’t offer any paid parental leave, said UW English professor Christa Olson, who used the policy to take teaching leaves after both her children were born.

However, this policy is not university-wide, Olson said, and it’s not an adequate substitute for paid leave.

“It’s better than nothing … [but] there are many things that are wrong with it,” she said.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated which employees are eligible for paid. All University employees are eligible.