For more than 30 years, a University of Minnesota neuroscience professor Eric Newman has worked to combat misunderstandings around brain cell function.

Now, Newman’s research on the cells and blood flow could lead to new treatments for diabetes.

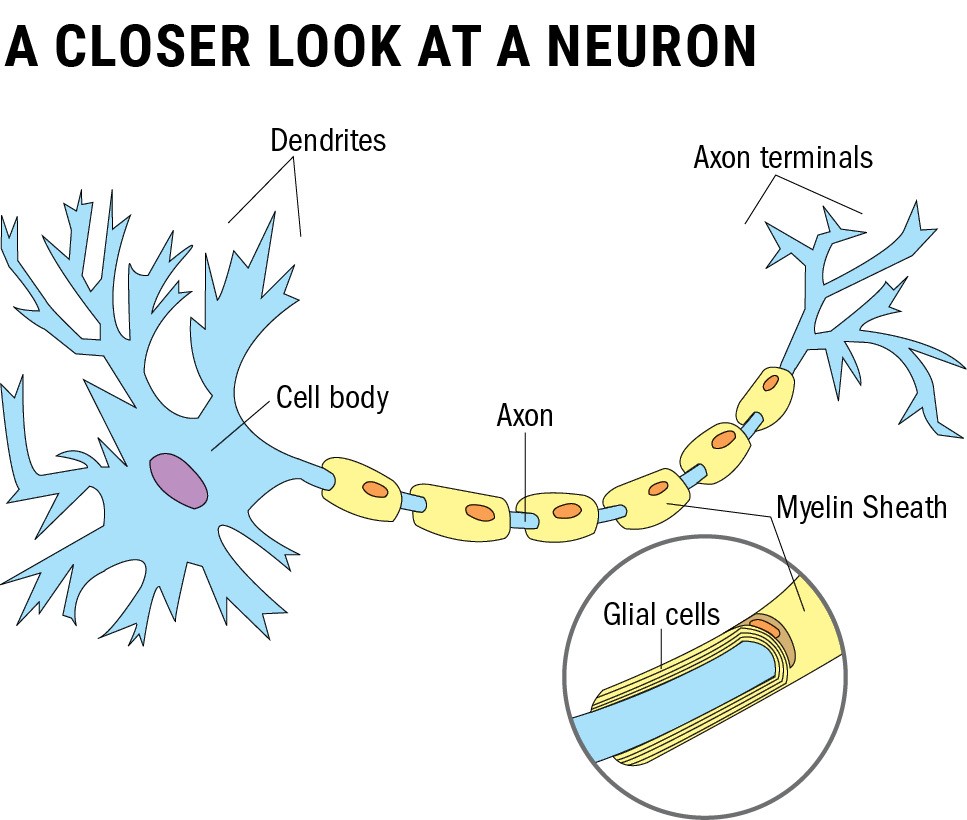

Glial cells have long been considered the “glue” that keeps the central nervous system together. Newman studies blood flow to see whether these cells have an active role regulating signals within the brain.

Hismost recent study showed how glial cells regulate blood flow in the retinas of mice.

“We thought glial cells were named from the German root meaning ‘glue,’” said University neuroscience professor Robert Miller, adding that scientists now understand that glial cells help clean up extra chemicals released by neurons.

Joanna Kur — a senior researcher in Newman’s lab — said the team studies blood flow in the retina by looking at the eyes of rats and mice under a microscope. They sometimes dye the cells or add poisoning agents to distinguish the specific glial cell they want to examine.

While glial cells were previously thought to balance nutrients for neurons to perform correctly in the brain, Newman’s research shows they also send signals across regions of the brain via small blood vessels.

He said this finding could lead to better ways to improve blood flow in the brain and prevent or lessen the impact of strokes. Other work by the lab could improve treatment of some diabetes cases.

“Glial cells, 20 or 30 years ago, were thought to be simple support cells,” Newman said.

While glial cells keep their ‘housekeeper’ role, he said more neuroscientists are recognizing the added abilities shown in his research. The number of peers who agree with Newman has slowly grown since the late 1980s.

Sidney Kuo, a post-doctoral researcher in Newman’s lab, said the findings on glial cells aren’t earth shattering or surprising based on his nearly 12 years of neuroscience experience.

Kuo said experts have known that glial cells may play a wider role for some time, but the lab is still working to cement that understanding.

Now, Newman and other researchers in the lab are working on a clinical trial of a new drug for blood flow in patients with Type 1 Diabetes.

Kur said the researchers hope the drug would inhibit an enzyme in the retina not regulated by glial cells, which can otherwise lead to impaired vision in diabetics.

But finding patients willing to participate in the study, Newman said, has proved difficult. He hopes to recruit 60 patients — half with diabetes and half without in order to continue his research.