The sight and smell of an old book is distinct. Its pages, now yellowed, are crisp and fragile.

At one point, it may have been someone’s favorite book — the past obvious in its dog-eared pages. Or it could have sat on a shelf merely for decoration.

Whatever its past life, you never know when that book might be worth hundreds.

Rare booksellers and collectors have created a culture where the copy-specific story of a book is what gives it value, not just what is written in the pages.

“It is ultimately a treasure hunt,” said Kristen Eide-Tollefson, founding partner at the Book House in Dinkytown. “It’s a matter of accumulating enough experience and general knowledge to be able to recognize when something is not just old, but important. Or not just rare, but meaningful.”

Eide-Tollefson and Book House co-owner Matt Hawbaker see themselves as the middlemen of the rare book world. They make house calls to dig through books in attics or help clean out a professor’s office in order to keep their own collection growing.

The rare book room at the shop houses prominent works, such as the complete first-edition of Voltaire’s writings and books signed by Richard Dawkins.

The room is small and in this, you can feel how important these copies are.

Of course, beloved collections also vary in size.

Rob Rulon-Miller is a member of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America and sells books out of his home in St. Paul. Here, almost every wall has disappeared behind shelves filled with books available for sale.

“I like selling a $50 book because someone is going to get it [and] appreciate it,” Rulon-Miller said. “God knows what that might spur them on to do as far as books go in the future.”

Rulon-Miller has been collecting and selling books for 50 years, handling about one million books by his estimate. What motivates him to keep seeking, researching and discovering is what these old books represent.

“It’s the story of human history,” Rulon-Miller said. “Even before printing, before Gutenberg, there are manuscripts that go back four or five hundred years. It’s the account of who we are, and we’re all enriched by knowing about them.”

Whether it houses the history of who shot President James Garfield or has simply been passed down through a family, value can be found in every book.

“If a first-edition of some novel is important, why isn’t a first edition of an important philosophy book just as valid in terms of value and scarcity? Everybody’s got different interests,” Hawbaker said.

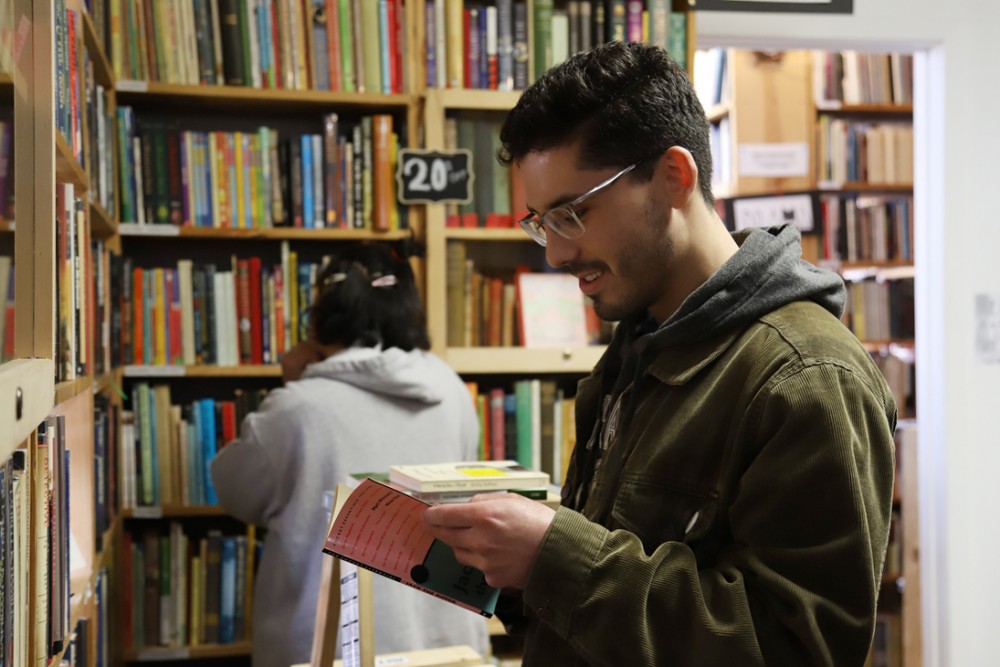

This seemingly niche interest begins with a common feeling, though.

“I think people are still pretty reluctant to get rid of books,” Hawbaker said. “Maybe it’s a generational thing, but I still see people my age and younger that are like, ‘this looks like it could be something.’”

Hawbaker admits that the book may not be worth a lot of money. Still, it can inform us about the past in an intimate way and inform those in the future about our own interests.

“Some of the stuff that I like to get my hands on are books where only one hundred copies were printed,” said Kevin Sell, the local collector behind the Instagram account @rarebooksleuth. “A lot of these things are being lost so it’s almost like an act of cultural preservation.”

In the same way that we look to the past to learn about our present, rare book collectors and sellers protect what they find now for future generations to study.

“We’ve always encouraged people to collect what they love,” Eide-Tollefson said. “Not to collect books just because they’re valuable, but to collect books because they’re meaningful to them as well.”

Formal training through Rare Book School and the Antiquarian Book Seminars are available for experienced and amateur collectors alike.

The will to continue the endeavor just comes with finding joy in the practice.

“We’re lucky to be able to do it,” Rulon-Miller said. “It takes a lot of dedication, but I can’t imagine doing anything else.”