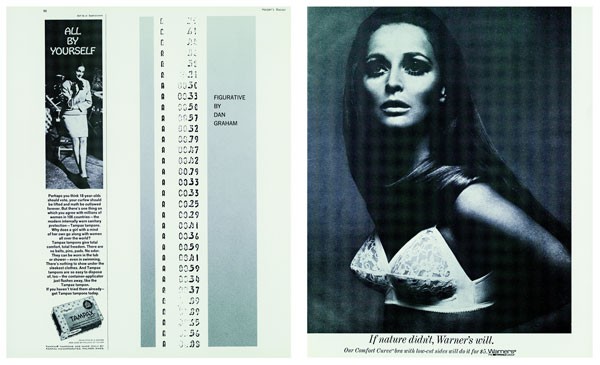

âÄúDan Graham: BeyondâÄù WHERE: Walker Art Center, 1750 Hennepin Ave. WHEN: Oct. 31 âÄì Jan. 24 âÄúBeyond,âÄù American artist Dan GrahamâÄôs touring retrospective, initially feels like a circus fun-house. The first room of the gallery is a mish-mash of looped videos, while pavilion models constructed from semi-reflective glass are scattered throughout the exhibition. Several stand-alone rooms protrude from the walls, waiting to excite children and intellectuals alike. At any moment, it feels like the floor will begin to move underfoot. There isnâÄôt a single medium that contemporary conceptualist Dan Graham hasnâÄôt worked in, and he often crosses boundaries, melding a sculpture into a video, incorporating graffiti into a work of brilliant architecture or turning an examination of tract housing into a aesthetic slideshow. âÄúDan Graham is one of those rare artists who has been consistently relevant and important âĦ since art was sort of turned upside down in 1960,âÄù said Chrissie Iles, the Anne and Joel Ehrankranz curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art. GrahamâÄôs most recognizable works are what he refers to as âÄúpavilions,âÄù sculptures of varying size made from the same semi-reflective glass used for skyscraper windows or those one-way mirrors that shows like âÄúLaw & OrderâÄù have made a symbol of the investigative process. The works function as a commentary on what Graham calls âÄúthe beginning of surveillance.âÄù âÄúThese are fun houses for children but also photo opportunities for parents,âÄù Graham said. âÄúThese anamorphic distortions of your body [have] a lot of Baroque feeling.âÄù This Baroque feeling becomes more apparent in the room featuring his installation works. In one room, a pair of video cameras and mirrors sits opposite each other, forming a virtual infinite extension space back into the gallery wall. As with all of GrahamâÄôs work, audience participation is a must. The full depth of the work is not realized until a group of people enter and interact with their own images. âÄúThese are environments; you activate them âĦâÄù said Bennett Simpson, associate curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Since the audienceâÄôs very actions are incorporated into the work, âÄúYou become very self-conscious of where your body is.âÄù Another room features two separate chambers, sectioned off by a soundproof glass wall. At one end of the chamber is a wall-sized mirror. Since the observation begins when the doors to the piece are closed, the audience will immediately feel both on display and as though they are watching something akin to a G-rated peep show. Much of GrahamâÄôs other works function in similar ways. His experimental films feature Graham speaking to a group of high school students. He begins by simply describing each of his subtle movements, such as the detailing of a shifting of his weight from right foot to left or bending of the elbow. Walking through the gallery, Graham points out his influences: The Rolling Stones , The BeatlesâÄô âÄúNowhere Man, âÄù Esquire Magazine and GrahamâÄôs personal hero, Dean Martin . Beyond themes of surveillance and different manifestations of the gaze is a fascination with pop culture, most specifically, rock music. His love of rock âÄònâÄô roll is outlined in an hour-long video-essay called âÄúRock My Religion.âÄù The film points out parallels between the song and dance religious movement âÄúThe ShakersâÄù and punk. The work is peppered with footage of Patti Smith, Sonic Youth and Ann Lee, the founder of The Shakers movement. GrahamâÄôs infiltration of popular culture didnâÄôt stop at music, though. One of his more prominent works of art was featured in the March 1968 issue of HarperâÄôs Bazaar. âÄúFigurativeâÄù is a collage of receipts, with the totals cut from the bottom. It functions as an exposition on desire; the constant yearning for consumption. The then-editor-in-chief of HarperâÄôs Bazaar understood this meaning and set the thin strip of numbers in the advertising section, between advertisements for a push-up bra and Tampax. Through constant evolution and changing of mediums, GrahamâÄôs work has taken on a form of sentience. Since âÄúBeyondâÄù features works that function mainly as mediums for reflection and audience incorporation, they fade into the background and become secondary to the experience of the exhibition as a room of wonder.

PHOTO COURTESY THE WALKER ART CENTER

The many angles of Dan Graham

“Dan Graham: Beyond” puts childhood fun and hardcore punk rock back into art.

by John Sand

Published November 4, 2009

0

More to Discover