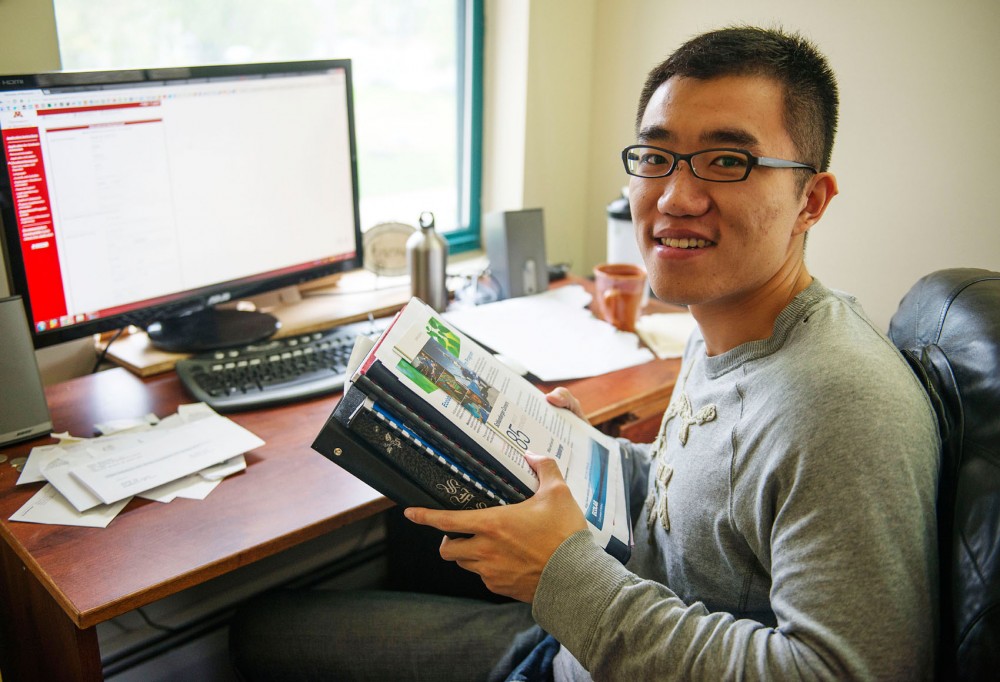

Haonan Sun was in a dilemma after graduating from the University of Minnesota in December.

The mechanical engineering student needed to find a job within three months after graduation or attend graduate school. Otherwise, Sun would have to go home to China.

“It was very stressful,” said Sun, who found a job at a medical device testing company. “Even if you haven’t decided what you want to do, you have to jump into the next phase right after you graduate.”

With limited jobs and work visas available, many international students either have to attend graduate school or go back to their home countries.

In 2012, more than 1,500 international students received degrees from the University, a more than 500-student increase from 2008.

Dong-Sung Kim, an economics junior from South Korea, said many of his friends had to go back to his home country after graduation because they couldn’t get jobs.

Kim said he’s working to build his career before graduation through internships and jobs so he has a better chance of getting a job when he finishes school.

“I don’t want to go back right away to Korea,” Kim said.

Newly graduated international students can get jobs under Optional Practical Training, a federal program that allows them to work in the country for an additional year.

Sun and other international students with science, technology, engineering or mathematics degrees can extend their OPT to 29 months.

“It’s very competitive to find a job,” Sun said. “And after that, you need luck to get a work visa.”

After their OPT ends, foreign degree-holders have to apply for H1-B work visas, which allow foreigners to legally work in the country, said Barbara Kappler, director of University’s International Student and Scholar Services.

“When they’re done being students, they can only use a limited number of options,” Kappler said.

The 85,000 available H-1B visas in the country this year ran out within five days, said Mark Schneider, an ISSS associate director for employment-based visas. Almost 39,000 requests were denied this year.

Schneider said applications for H-1B visas can cost companies $825 each, and many of them don’t know how to handle H-1Bs, which can cost companies more than $2,000 in attorney fees.

“That can be expensive and prohibitive for some employers,” Schneider said.

Because of the complicated and costly process of hiring degree-holding foreigners, Schneider said many companies decide to hire American applicants with the same degree.

A current U.S. Senate immigration bill would increase the number of available H-1B visas to 110,000, said Schneider, who works on H-1B visas for incoming employees. If the bill doesn’t pass, he said he hopes the cap increase could move forward in another piece of legislation.

Schneider was in Washington, D.C., in March to advocate for more H-1B visas and fewer barriers for international students when they enter the working world.

“You get ’em here, you educate them and then they have nowhere to get a job,” Schneider said. “There are lots of barriers.”

Many universities and companies have also been pushing for a higher cap on H-1B visas so employers can have more hiring options and students have more job opportunities, Schneider said.

Sun said he considered himself lucky to find his new job, which he starts in June.

Most of the jobs Sun applied for turned him down when he said he would need sponsorship to get a work visa in the future.

“We need to welcome students, graduates and highly skilled laborers into the United States,” Schneider said, “because that’s the future of the economy and our country.”