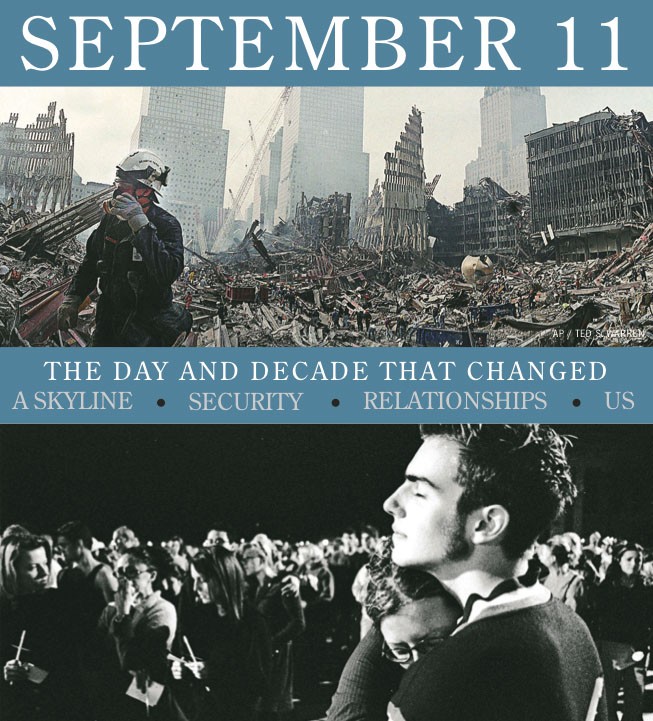

On that Tuesday 10 years ago, campus life halted as students crowded screens to watch horrifying events unfold.

Now a new generation mills through campus.

For students now, the attacks have sat in the shadows of our minds since that Tuesday in grade school. Maybe a teacher walked in and explained what happened, which sounded at first like an accident. Or maybe that afternoon mom or dad explained the tragedy in simpler terms.

WeâÄôve come of age in a new kind of world âÄî where America looks at certain people longer or differently.

That day on campus was the start of it. Some say a community known for open minds became closed, and all say it changed.

WeâÄôve weathered a recession, watched revolutions rage in the Middle East and argued if we should intervene. As a nation, and as a campus, we have new leaders.

But now is a time to go back to the ground zero of our minds.

Anger, confusion, concern.

What happened?

Rumors spread, TV sets switched on. They got another plane. ThereâÄôs another hijacking.

WhatâÄôs next?

Phones rang, schedules changed, eyes welled.

Still, 10 years and two wars later, we ask:

Why?

A tangled day

Students walked toward Northrop Mall, seeking answers on that Tuesday.

Where should we go? Are we in danger?

Morning classes became forums for discussing what had happened and watching the news.

The University of Minnesota canceled all classes after noon âÄî the first time it had done so in 10 years.

Then-University President Mark Yudof showed up on the mall, comforting students.

The Sept. 12 issue of the Minnesota Daily was full of reactions: An engineering professor analyzed the planesâÄô force that led to the collapse of the World Trade Center. A management professor touched on how the world economies would recover. In that issue and those that followed, students reacted with quotes in stories and with letters to the editor that called for unity and compassion, analysis and answers.

Yudof, who now heads the University of California system, wrote a letter to students in the Daily, published along with resources for counseling, blood donations and information on missing people.

Before signing off by requesting prayers for those who knew victims, Yudof asked of University community members: âÄúPlease take a moment to call your families and other loved ones to let them know you are all right.âÄù

Vigils and prayers filled campus in the next days.

Amelious Whyte, a Brooklyn native and now chief of staff in the Office of Student Affairs, remembered one moment on the mall when a minister led a reading of the LordâÄôs Prayer.

âÄúThey get to the part where it says, you know, âÄòForgive those who trespass against us,âÄôâÄù he said. âÄúI couldnâÄôt say that.âÄù

As much as confusion reigned over campus, some assumptions were made, said Taqee Khaled, a student at the time.

âÄúIt was actually, I would say, an early assumption of âĦ what type of group was responsible,âÄù he said, âÄúand I knew what that would be.âÄù

Unity excludes Muslims

In the shock and haze of hearing of the second, third and fourth prongs of the attacks, students met on the mall.

âÄúPeople just found people that they knew and just kind of wanted to be around other people because they just didnâÄôt know what was happening or how to process it,âÄù Khaled said.

But as the shock faded and facts came to light, some students vented their anger and focused their blame.

The worst case was a student who ripped off a Muslim womanâÄôs hijab and spit on it.

But beyond that, there was little physical harassment of Muslims on campus. More prominent were changes in behavior, appearances.

Those changes were far-reaching âÄî everything from off-hand remarks to haircuts.

âÄúIâÄôm gonna be honest âÄî the first day or two âĦ there was a lot of backlash,âÄù said Wissam Balshe, who was president of the Arab Student Association at the time.

BalsheâÄôs phone number was listed with the student group. His voice mail box filled with nearly a dozen fuming voice messages that Tuesday.

Many of his Arab friends dyed their hair or shaved their beards, which were sometimes worn to emulate IslamâÄôs Prophet Muhammad.

Women stopped wearing hijabs because they were fed up with sideways looks and angry words.

That Tuesday on the mall, Yudof approached Khaled.

âÄúThe University is with you,âÄù he remembered Yudof saying. âÄúDonâÄôt worry about anything.âÄù

âÄúIt was a pretty brilliant moment,âÄù Khaled said.

Ten years later, University President Eric Kaler wrote in an email to the Daily that he hopes such stereotyping has vanished from campus.

âÄúIt is too easy to stereotype,âÄù he wrote. âÄúWe should as a community and as individuals be too smart for that to

happen.âÄù

Some of BalsheâÄôs group members disappeared âÄî they went back to their home country or dropped out of school. Some stayed home the first few days after that Tuesday to avoid the worst of the mistreatment.

Some non-Muslim friends just werenâÄôt friends anymore.

Before that Tuesday, BalsheâÄôs group was politically loud on campus, with pro-Palestine events, for example.

After that Tuesday, the group dithered. Some didnâÄôt want to be as open about their roots, he said.

âÄúThey just didnâÄôt want to be seen as Arab anymore.âÄù

Centralizing safety

Calls to University police jumped, and were often to report sights that would go unseen before the attacks.

âÄúEverybody in the campus community was âĦ tense, as was, you know, the nation, and not sure about what might happen next,âÄù said Deputy Chief Chuck Miner, a patrol sergeant at the time.

He said the tension took a couple of months to dissipate.

Some of the uptick was related to what Balshe experienced as a Muslim. Callers would report, for example, an Arab person taking pictures of buildings, Miner said.

Others told of white powder on a drinking fountain.

If a small plane flew over a gathering, someone might have called it in, just in case.

That TuesdayâÄôs effects on campus security have shaped todayâÄôs public safety, from extra bag inspections at football games to a Joint Terrorism Task Force liaison in University police.

âÄúCertainly things on campus began to change from that night forward,âÄù Miner said.

Tucked into one floor of an office building next to TCF Bank Stadium, a sweeping unit has eyes all over campus. The Department of Central Security is just how it sounds âÄî a centralized office for all University security matters.

Centralizing security responsibilities didnâÄôt overhaul the public safety system âÄî it was a new model of efficiency, assistant director Steve Jorgenson said.

Security cameras, card access and administration were once scattered among other University departments. Now itâÄôs all under the central security umbrella.

âÄòPeople are resilientâÄô

After Sept. 11, family stood out more to Jerry Rinehart, the UniversityâÄôs vice provost for student affairs.

âÄúI saw a lot of people and heard of other people making some major life changes after that,âÄù like switching from jobs to hobbies, Rinehart said, âÄúbecause so many had lost so much so quickly.âÄù

It wasnâÄôt an unusual reaction, as one study showed that the tragedy made many Minnesotans more appreciative of life or family.

A study co-authored by a University professor showed that most of 188 students surveyed three months after that Tuesday saw positive changes. The changes ranged from those that Rinehart noted âÄî 41 percent reported better relationships with family âÄî to a better appreciation of life and of the good in people.

Half reported that the biggest overall effect was positive.

The negative changes were, the study showed, more intangible: less faith in the safety, fairness and justice of the world.

âÄúWe have this idea about trauma: that itâÄôs just devastating and people just never get over it,âÄù co-author Patricia Frazier said.

But, she and the survey results say, people are resilient.

Even after the most tragic events like Sept. 11, Frazier said, âÄúyou go on.âÄù