A handful of students banded together to save Dinkytown’s character, producing a documentary about its history and soliciting donations.

“The faces and names change in Dinkytown, but the heritage remains …” they wrote in an editorial. “Now is the time to start preserving this heritage.”

That was 40 years ago.

Today, students are still fighting to save what they think makes Dinkytown special.

“It’s the only place that students have,” University sophomore Rebecca Orrison said. “One of the really cool things about coming to the U is having Dinkytown.”

For more than a century, the four-block area has shifted and transformed to meet the University of Minnesota’s needs.

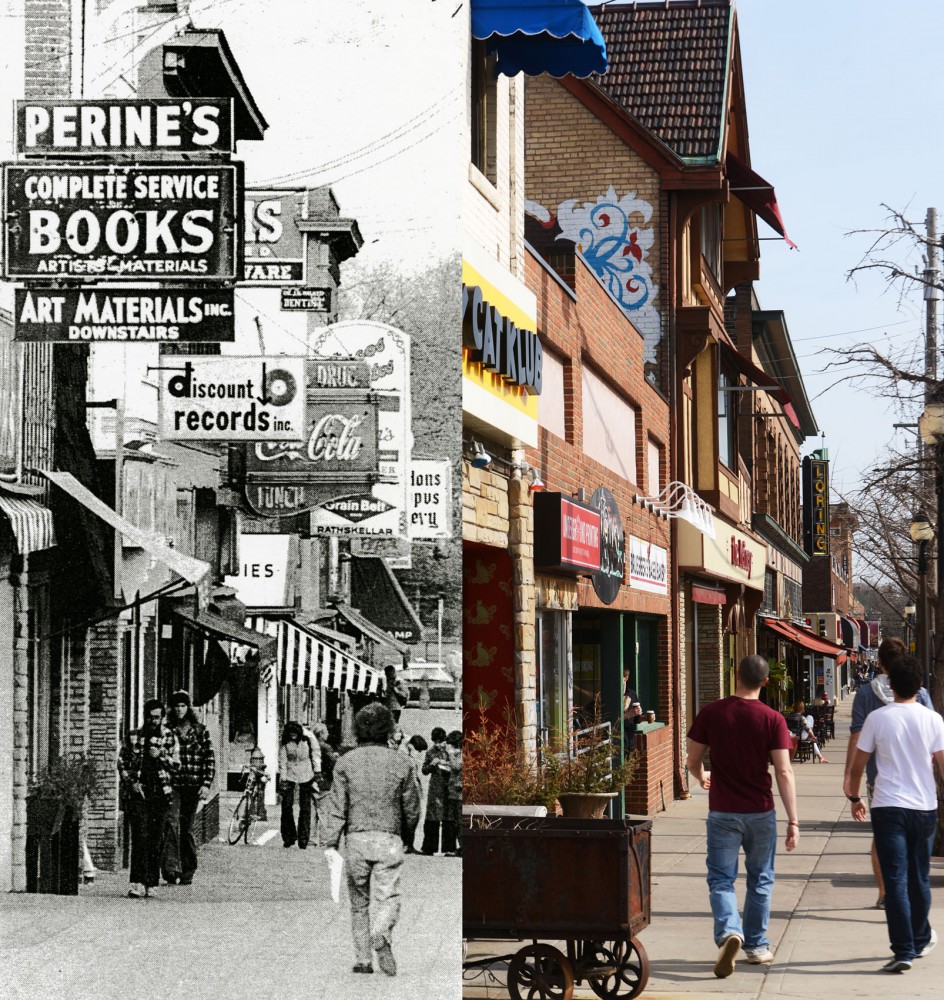

The Dinkytown of yesteryear, where the campus trolley ran, Bob Dylan began his musical career and businesses like Bridgeman’s Ice cream and Meyer’s Grocery became mainstays, is not so different from today’s. Dinkytown is, and always has been, a reflection of what students need and want at the time.

Whether it’s adding more bars and chain restaurants or new student housing, Dinkytown is constantly evolving — but it’s a trend that continues to stir controversy.

‘You can’t buy a pair of socks now’

Dinkytown today is an entertainment district and foodie destination — more than half of its storefronts are restaurants and bars.

But 50 years ago, service-driven businesses, like hardware stores and dry cleaning were dominant in Dinkytown.

Retail, service and food were equally represented 20 years ago.

Then the city lifted an area liquor ban — put in place to prevent drinking close to campus — and bars emerged.

Today, the transformation from self-sufficient village to entertainment district is complete.

Loring Pasta Bar was then Gray’s Campus Drug; Espresso Royale has taken the place of 115-year-old Simms Hardware and Perine’s Bookstore bookended the Dinkytown stretch of 14th Avenue that now serves Annie’s malts.

In the ’80s, “a person could basically walk into Dinkytown and get everything you’d need, just like it was a small town,” said Jim Picard, owner of Fast Eddie’s shoe repair.

Today, retail has diminished and restaurants rule the business landscape, partly because of students’ increased mobility.

In the past, students depended on nearby Dinkytown for groceries and school supplies, but as they began bringing cars to school, students ventured off campus to shop.

Not everyone is lamenting this change — some students are happy with Dinkytown as a food hub.

Retail, especially clothing, has decreased. Dinkytown has been home to stores like Al Johnson menswear, thrift shop Everyday People and family owned jewelry stores and gift shops.

Today shopping options are limited, Picard said.

“If you wanted to buy, for instance, a pair of socks, you could,” he said. Now, that’s not possible, “unless you want some with a picture of Goldy on it.”

Individual businesses today, especially unique restaurants, are the destination for customers — a trend that has eroded the cohesion of the area, said Mary Rose Ciatti, who’s been a server at Al’s Breakfast for 25 years.

When Steve Bergerson, who was part of student organizers in the 1970s, attended the University, a liquor ban meant the area was more active during the day. The granting of liquor licenses in recent years has “changed the texture of Dinkytown,” he said.

In 1999, Irv Hershkovitz’s Fowl Play was the only bar in Dinkytown with a hard liquor license; today, there are three bars and Hershkovitz’s Dinkytown Wine and Spirits.

Before there were bars, students had to go downtown for nightlife, so having late-night businesses closer to campus has been positive for students, said Marcy-Holmes Neighborhood Association President Doug Carlson.

But the dominance of restaurants and bars bothers Hershkovitz.

“I just hate to see Dinkytown be only bars and restaurants,” he said, “it needs these other things.”

Commercializing Dinkytown

Dinkytown has also shifted away from local small businesses toward larger chain stores.

The resulting tension boiled over in 1970 when students and residents protested the construction of fast-food franchise Red Barn at the site now housing the Dinkytown post office.

That spring, 300 demonstrators faced off with 100 police officers and sheriff’s deputies.

After protesters were forcefully removed and the site was demolished, students — including Ciatti — moved in and created the “People’s Park,” planting flowers and setting up swings.

Faced with so much opposition, Red Barn representatives gave up plans for a Dinkytown branch.

Today, that sort of resentment remains among long-time Dinkytowners and students.

Ciatti said she began to see major changes in the ’80s, when larger chains drove out historic Dinkytown establishments like Mama D’s Italian restaurant and Gordon’s Campus Bakery.

“All of the restaurants that are big now are chains, and they’re driving everything else away,” architecture sophomore Jessica Vetrano said as she stood on 14th Avenue.

Environmental science sophomore Orrison said she felt Dinkytown was doing its best to hold on to long-time local businesses.

“It’s really hard to go anywhere and not find chain stores,” she said. “I think Dinkytown has done a better job at resisting that national trend.”

Chain stores can simply afford the price of a Dinkytown location, Ciatti said.

“People come in and buy the buildings and raise the rents,” she said. “The so-called mom and pops and one-of-a-kinds had to leave because they couldn’t afford it — it’s just really sad.”

The assumption that the proximity to students automatically brings profits is partly why some businesses in Dinkytown fail, Hershkovitz said.

“Everyone — and I mean national tenants, mom-and-pop tenants, everyone — thinks because you have 53,000 students across the street, all you have to do is open your doors and you’ll be successful,” he said. “That just isn’t true.”

Four businesses along 14th Avenue now sit empty from recent closings.

Student housing booms

In recent months, the University Technology Enterprise Center was torn down after 90 years of serving as a high school and office space.

Halfway through demolition, the massive building stood mangled and gutted, a carcass of its former self. The site is now a plot of dirt.

In fall of 2014, a 317-unit apartment complex will sit in its place.

Along with other proposed projects, the UTEC project is ushering in a new era for Dinkytown by addressing the most recent student need: student housing close to campus.

Across the street, a proposed Opus Group apartment building, if approved by the city, would provide 140 more units in Dinkytown as well as retail space. The Book House, House of Hanson and the Podium would be torn down.

The UTEC apartment complex is currently finalizing rental agreements with a grocery store for its ground-floor retail space.

The projects follow a campus trend — in the next two years, more than 1,500 student housing units are slated to open on the University’s East Bank.

Fast Eddie’s owner Picard said such expansive projects would destroy Dinkytown’s unique physical character, which today is defined by its hodgepodge of smaller properties and architecture.

Businesses across the street from Fast Eddie’s, like Mesa Pizza and Hideaway, sit in a patchwork of individual buildings.

On the other hand, the block along 15th Avenue that includes CVS Pharmacy and Chilly Billy’s is dominated by 125-unit luxury apartment complex Sydney Hall.

The overall landscape of Dinkytown, Picard said, is “made sort of plain” by giant buildings that house both residents and businesses.

Mixed-use buildings are common in most business districts in Minneapolis, said Carlson, president of the MHNA, but Dinkytown may still need limits on development.

“The last thing we want to have happen is to … have each block be completely occupied by mixed-use developments that are right up to the sidewalk and straight up five or six floors,” he said.

Carlson and others say they believe the apartment project replacing House of Hanson in particular will encroach on the heart of Dinkytown.

Nearby apartments like 412 Lofts, the Chateau, Sydney Hall and the UTEC project are located closer to the periphery of the district.

For Ciatti, who grew up near the area, the separation of business from residential properties is essential to Dinkytown’s character.

“It pisses me off,” she said. “It’s OK to put in housing around us, but when you move into the business district … that is so wrong. It’s the beginning of the end.”

Enhancing or encroaching?

At night, Dinkytown draws people of all kinds, with the low-key Kitty Cat Klub and the rowdy trio of Library Bar and Grill, Burrito Loco and Blarney Pub and Grill.

“It produces an interesting mix,” graduate student Sam Beddow said. With new apartments, he said he fears Dinkytown will lose its diversity.

As with any major changes, the new projects came with contention and added fuel to an ongoing debate on what parts of Dinkytown shouldn’t change.

New developments are long overdue, said Hershkovitz, and the area needs a face-lift.

Some of the buildings are dilapidated, and the neighborhood has survived several fires that destroyed entire businesses.

“There’s only a couple of buildings left that have character — the rest are just not very nice,” Hershkovitz said. “[Dinkytown] needs new businesses and buildings that don’t look like they’re about to fall over.”

Some students are concerned for the loss of local businesses in the wake of new development.

“It’s kind of a shame that they’re getting rid of all the small businesses around here and building all these big apartments,” electrical engineering junior Eric Kallevig said. “There’s kind of enough, don’t you think?”

The Opus project especially has received pushback from the community, spurring a “Save Dinkytown” group that’s protesting the development and its possible zoning changes.

“There’s nothing that looks like this project,” said Orrison, a University student and member of the group. “[Dinkytown is] this really cool patchwork quilt of pastel colors, and they’re going to take out one of the spots and put in a neon green one.”

In order to preserve Dinkytown’s character, Carlson said the Dinkytown Business Association should pursue a conservation district status and continue working with the city to create a small-area plan with guidelines for developers.

Retrofitting and renovating older buildings, like Loring Pasta Bar and Varsity Theater have done, is another way to continue development without sacrificing character.

“These old buildings,” Picard said, “as beautiful as they are historically, they either have to be restored or saved or something else moves on.”

Dinkytown looks back, moves forward

Painted, then faded and worn over the years, names of former businesses remain on the sides of Dinkytown buildings like the height markings of a growing child on a wall.

One hundred and thirty years ago, with a stable, feed store, blacksmith shop and railway depot, Dinkytown developed. It sat outside a handful of buildings that at the time comprised the University of Minnesota.

Many say Dinkytown will continue to be a special place for students, an off-campus campus and middle ground between the University and the city.

But although it’s always evolving to meet student needs, Dinkytown’s tradition as a University institution will remain.

“As long as the University is around, Dinkytown will be around,” Picard said. “It’s going to be different, but it’ll always be here.”