Finding an executive-level administrator to fill an open position at a university comes at a cost.

Some officials say schools lack means to conduct large-scale searches to find the perfect fit, which can take months and lag on for even longer if candidates don’t accept an offer.

So nationwide, colleges turn to companies to track down and vet candidates, in order to expedite what can otherwise be a long and tedious process. By mining a deep network of contacts, a search firm can target a handful of potential hires in a sliver of time.

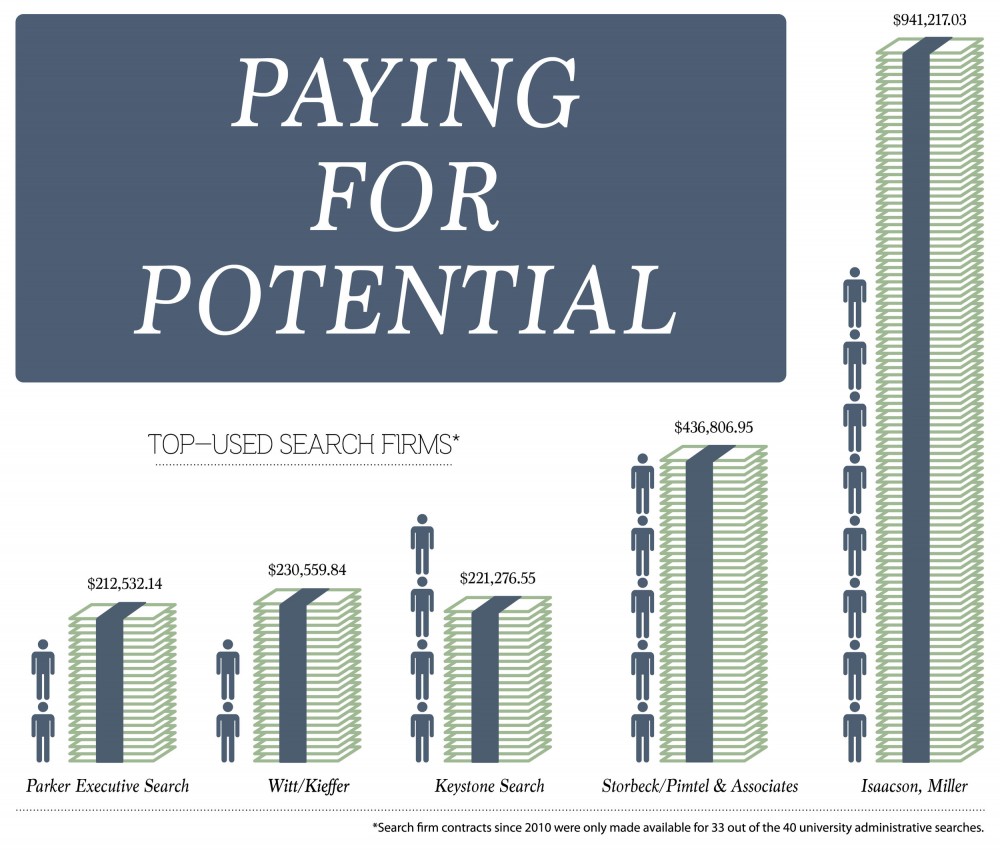

But some consider search firms — which typically charge one-third of the candidate’s estimated salary, or the median of about $98,000 at the University of Minnesota — too expensive.

The University came under heavy media scrutiny for their use of search firms in hiring both former athletics director Norwood Teague, who resigned last summer after admitting to sexually harassing two female coworkers, and Chief Information Officer Scott Studham, who stepped down one month later.

Public records requests showed Teague and Studham had complaints lodged against them prior to their arrival at the University.

But search firms tend not to request that information during the vetting process.

Instead of digging deep into candidates’ pasts, firms typically ask potential hires to disclose any previous complaints against them, said Kurt Rakos, a co-founder and partner at Skywater Search Partners, a Minnesota recruitment firm. If the candidates disclose nothing, he said, the firms take their word for it.

Despite criticism from the public as well as state and University officials, President Eric Kaler announced last month the school will use a search firm to find its next athletics director. His announcement came two months after he said the University was leaning toward conducting its own search.

The benefits of using a search firm, like providing a wide and diverse pool of candidates, outweigh the costs, Kaler said.

Selecting a match

Each of the 14 Big Ten colleges goes through a search firm when looking to fill a top administrative position, which calls for a monthslong process of profiling, interviewing and negotiating with candidates.

Using a firm is common practice among educational institutions because it can eliminate a school’s bias from the hiring equation, said Sen. Greg Clausen, DFL-Apple Valley.

Though most universities use search firms for similar reasons, deciding which firm to hire varies school to school.

For example, the University of Maryland fills different levels of administrative positions using firms, which are chosen based on specialization in the open position’s field, said Assistant Vice President for Human Resources Jewel Washington.

Like the University of Minnesota, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln mainly uses search firms to fill higher-level administrative positions and doesn’t necessarily prioritize specialty firms, spokesperson Steve Smith said.

A search firm will first discuss with the school about desired candidate traits and the position’s history and then build a job description to pitch to potential hires, Rakos said.

Typically, search firms seek out candidates who aren’t looking to leave their current positions, Rakos said, so hiring companies must carefully frame the opening.

Often, search firms sift through a database of candidates, many of whom they have already interacted with, said Carlson School of Management Work and Organizations Professor John Kammeyer-Mueller.

Higher salaries and promotions can win over unsure candidates, who typically ask that the process remain confidential to keep their current employers out of the loop, Rakos said.

The University of Illinois opted to search for a new athletics director itself, Kaler said, which put candidates’ current employment at risk after it sent emails to their work addresses. He said using a search firm would help the University of Minnesota avoid similar missteps.

A series of interviews and criminal background checks help to initially vet the applicant.

Without a search firm, a university’s leader could push to hire a candidate with personal connections instead of considering others, Kammeyer-Mueller said.

If there’s a hiccup within the chosen candidate’s first year of employment — for example, they leave or are fired — the search firm will begin another headhunt at no cost, he said.

Despite initial estimates for total cost, the final price remains unknown until the search process is complete, said Katie Stuckert, director of human resources for the University of Minnesota provost office.

The final cost usually doesn’t match original projections — and sometimes exceeds them — but typically falls within about $5,300 of the estimate.

Cost also varies based on the position being filled. Finding Medical School Dean and Vice President of Health Sciences Brooks Jackson cost the school nearly $260,000, whereas the search for University of Minnesota Police Chief Matt Clark cost about $30,000.

Weighing the pros and cons

Kaler’s decision to externalize the search for a new athletics director divided regents and legislators.

University of Minnesota regents voiced their support or concern regarding the move during a Feb. 12 Board of Regents meeting.

Though search firm fees are high, Regent Richard Beeson said, they can broaden the University of Minnesota’s search for candidates to a national degree.

Regent Thomas Anderson said the school needed to be “all in” with its efforts by conducting its own search alongside a firm’s.

The University of Minnesota plans to do just that, Kaler said.

“I think the past searches where we have used search firms have, by and large, been successful,” Kaler said.

Still, Anderson said he’s noticed criticism from Minnesotans, including some from his hometown of Alexandria, Minn.

“I go back home, and people complain about what the University [of Minnesota] spends,” he said.

And the cost isn’t worth it to Regent Darrin Rosha, who said he thinks hiring an out-of-state athletics director without ties to the state is a cause for concern.

That disconnect, he said, could lead the athletics director to use the University of Minnesota as a launching pad to polish his or her resume before moving somewhere else.

Rosha said there are enough potential local and state candidates — like Interim Athletics Director Beth Goetz, who announced last month she hopes to continue as athletics director permanently — to forgo the use of a search firm.

“Even if you do wind up with somebody who’s favored, they’re validated by the search and have stood up against the best available candidates from across the country,” Kaler said.

Rep. Gene Pelowski, DFL-Winona, pointed to troubles in the Minnesota State Colleges and Universities’ system — where use of search firms mirrors the University of Minnesota’s, but college presidents have a track record of not sticking around. In 2013 and 2014, Pelowski said, only a few MnSCU administrators were hired internally.

“I’m not sure if there are any priorities anymore in higher ed except to get the best salary and find wherever it is the next place you want to go to get a better salary,” he said.

Rosha added that good donor, community and fan relations are required for the job, and he questioned whether a search firm has the ability to quantify those skills.

Without that support, he said, an athletics director would struggle to recruit coaches and fill arenas.

Critics said that the search firm should have found a 2012 settlement of $125,000 between VCU and a women’s basketball coach over a Title IX gender discrimination complaint she filed against Teague.

But an external legal review found the prior complaint would have likely been missed, whether a search firm was used to hire Teague or not.

“The search process was not the reason that we got a guy that turned out to behave very badly,” Kaler said at a Feb. 11 Board of Regents committee meeting.

Lawmakers have raised concerns in the past over high turnover among search firm hires, said Rep. Gene Pelowski, DFL-Winona.

Though he said he doubts higher educational institutions will ditch search firms, lawmakers can’t legally control the schools’ decisions, either.

“You have that old adage of, ‘If everyone else jumps off the bridge, why shouldn’t you?’” Pelowski said. “Apparently, we’ve had enough jumping off the bridge this year that people should know it’s a long way down.”