Pam Davies spent a year waiting for a new liver as she grew sicker every day. Eventually, she got two-thirds of what she wanted.

Davies, a business and life coach, underwent a split liver transplant in 2013 at the University of Minnesota.

The procedure takes one donated liver and splits it into two differently sized lobes, saving the lives of two patients.

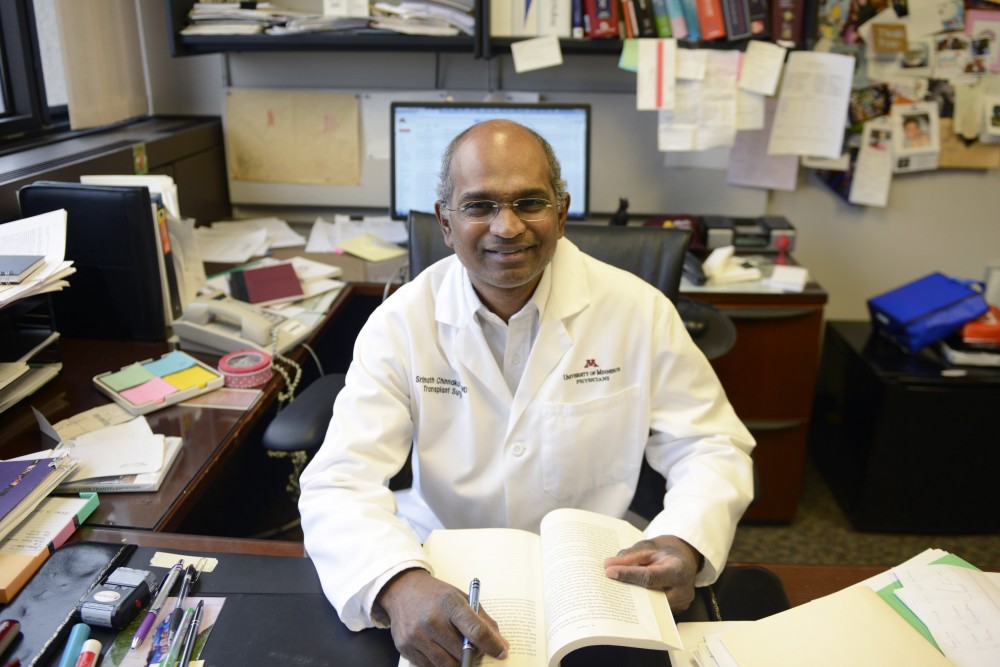

Srinath Chinnakotla, the University’s surgical director of the liver transplant program, performed the split liver transplant on Davies; the technique was developed almost 25 years ago, and Chinnakotla says more doctors should adopt it.

Chinnakotla said patients have to be smaller in stature for the split liver transplant to work, and many children receive the smaller liver portions.

“The number of livers available in the country to split are close to 2,000,” Chinnakotla said. “Less than 200 are being split every year.”

After spending years working long hours and traveling constantly for most of her life, Davies said she neglected self-care and was constantly busy.

She said she was diagnosed with a thyroid condition in her late 20s but kept pursuing her career. The thyroid disease caused Davies to develop a metabolic disorder which eventually resulted in a diagnosis of non-alcohol-related fatty liver disease in 2011.

“You’re ending up with fatty deposits in your liver,” she said. “I had no idea that was going on.”

Davies said she woke up one morning to find her skin turned yellow and was diagnosed at the University’s hospital system. She said doctors told her the liver disease could kill her in one year if she didn’t receive a new organ.

After gaining weight due to the disease over the previous year, Davies found she was too sick to even be on the liver transplant list.

With the help of a hepatology team at the University, Davies said she lost 100 pounds over the course of seven months.

“My job suddenly became getting on the transplant list and trying to stay alive,” she said. “I spent a whole year on the transplant list and was still getting sicker.”

In 2013, Davies said Chinnakotla and his team told her they had a liver available, but that the transplant was going to be different than typical transplants. She agreed to the surgery and left the hospital six days after it was completed.

“It is such an amazing situation that they were able to save two people,” she said. “I was so small, that they were able to take two-thirds [of the liver] and give that to me.”

She said she had never heard about this type of surgery before it was performed on her by Chinnakotla.

Chinnakotla said many doctors initially assumed the split-liver transplant would result in more patient deaths.

He said studies done in the last five years show that patient survival after a split liver transplant is no different than whole liver transplants, though bile duct complications are 10 percent higher.

Chinnakotla said bile duct complications are easily treatable and don’t compare to the possibility of saving two lives with one organ.

Not all livers can be split, and the donor has to be under 40 years of age.

Besides a lack of experienced surgeons, Chinnakotla said the research policies that help allocate livers to patients don’t favor splitting the organ. Many doctors don’t want to take the risk of splitting the liver if they could safely use the entire thing.

Chinnakotla said in 2015, 10 percent of child patients and 20 percent of adult patients waiting for a liver died on the waiting list.

About 7,000 livers were donated last year.

“In a conservative estimate, if we think 25 percent of them are splittable, we have about 500 donors that can be split,” he said. “But in general, we are only doing 100 splits a year.”

In his entire career, Chinnakotla has completed over 20 split-liver transplants, five of them at the University. The University of California-Los Angeles also performs a majority of the split procedures in the United States.

“Splitting a liver needs some expertise,” he said.

Susanne Hollister, a liver transplant social worker, helps patients like Davies psychologically work through the transplantation process and said she reviews whether patients are healthy enough to receive the new organ.

“Part of the difficulty … is waiting,” Hollister said. “They don’t know when a transplant is going to occur. There needs to be a donor available.”

She said the evaluation process and the recovery for patients receiving a split liver is the same as if they were receiving a full liver.

“Obviously we don’t have enough organs for everybody,” she said of people on the waiting list.

Hollister added that the technique is one way to help ensure that more people are transplanted.

“Anything we can do to increase the availability of donors would be very important,” she said.