First experiments are underway in Amundson Hall’s new Gore Annex expansion — complete with new lab facilities, teaching spaces and a first-of-its-kind ultrafast electron microscope.

“We’re moving in hot,” said teaching assistant professor Mike Manno. “We got new equipment coming in every day, new things are being installed and the students are slowly coming in.”

Faculty and students from the University of Minnesota’s Department of Chemical Engineering and Materials Sciences are moving into their home’s new addition, funded by donations from industry partners and a prominent University of Minnesota alumni technologist.

The Gore Annex’s six floors include new material science and biotechnology labs that will assist efforts to develop sustainable plastics, advance semiconductors and new cancer fighting strategies, said department director Dan Frisbie.

The department launched the $30 million, 40,000-square-foot add-on to meet expanding student demand for space.

“It’s the key to the future of the department,” he said.

Although the number of chemical engineering students has remained steady, Frisbie said the department’s materials focus has seen major growth.

“Twenty years ago we had maybe a dozen [materials science] majors a year,” he said. “We now have 65 majors in the junior class.”

The program could almost certainly increase to 100 students a year, said regents professor Frank Bates.

“This field has evolved — it’s sort of exploded nationally as probably the highest growth area in engineering and applied science,” said Bates, who headed the department from 1999 until this summer.

Developing new materials has become a vital area for building blocks needed to advance energy, health care and information technology, Frisbie said.

“Materials drive technology,” Frisbie said. “If you look at the microelectronics industry, it’s driven by our ability to make and process silicon.”

A long-awaited expansion

Amundson Hall saw its most recent expansion in 1999 when it added the Piercy Wing.

An expanding student body began cramming the building’s increasingly tight space, Bates said. Students outside the department also exacerbated the space issue.

“We had to jam them and our own students into a rather substandard space,” Bate said.

Private donations from Dow Chemical Company and a department alumnus, along with $15 million from state and University sources, make Gore Annex one of the most privately capitalized buildings on campus, Bates said.

Along with benefiting materials sciences students, the expansion will give room to chemical engineers.

Samira Azarin, an assistant professor in the department since August, said Gore Annex will provide her space to research and develop cancer therapies using chemical signals in cells.

“A lot of times you’re limited by the building that you’re in,” Azarin said. “[Having] the room to expand and grow my lab and not have to worry what’s going to happen in five years when I have more students — that was very appealing to me.”

She said researchers will more efficiently leverage resources by sharing the new laboratories.

“As a new professor, you have to start your lab from scratch,” she said. “There’s a lot of equipment I don’t have to buy because it’s already here.”

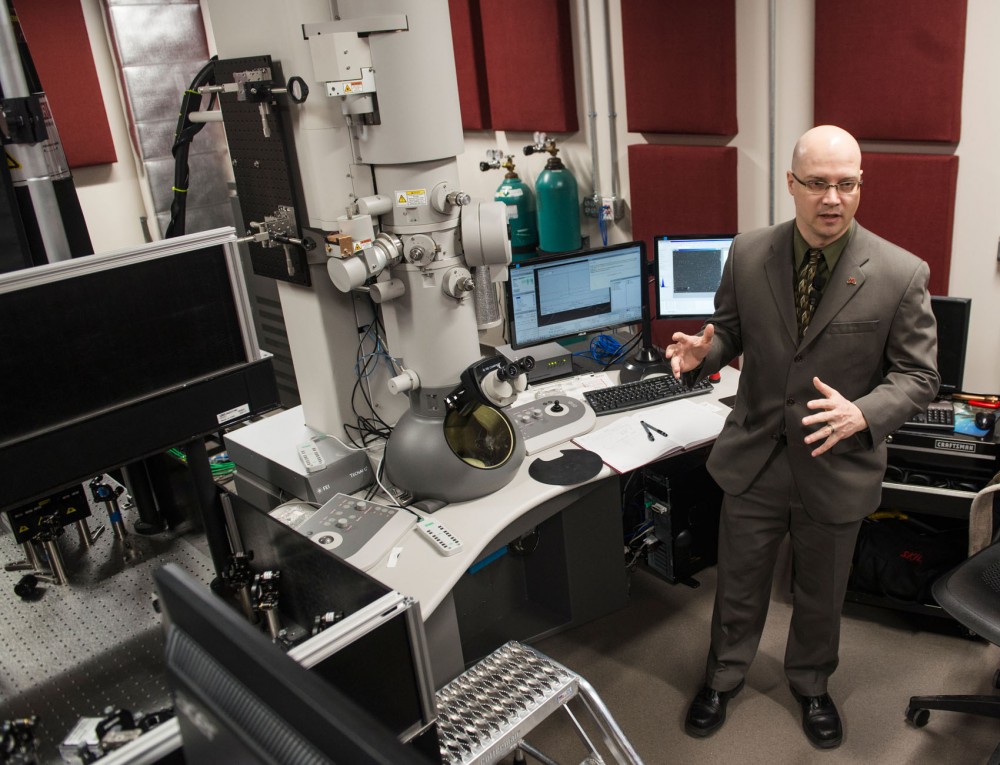

Along with boosting lab space, the Gore Annex also sports the first of a new line of electron microscope technology.

The device uses a laser system that allows researchers to record atomic motion over spans of time measured at one-millionth of a billionth of a second, Frisbie said.

“We’re talking about time scales at which molecules vibrate,” said assistant professor David Flannigan.

Using the microscope, scientists can probe and harness the materials’ fundamental properties. For example, Flannigan said, some engineers will use it to examine how heat dissipates and then design hard drives that can hold more space.

Nestled in a basement laboratory specially designed to isolate the sensitive equipment from vibrations, Flannigan said, the microscope will put the University on the cutting edge for decades.

“The microscopy capabilities in this department right now are just incredible,” Azarin said. “We can ask questions we might not even have thought of yet.”

Bates said about two years ago, FEI Tecnai, the company that manufactures the microscope device, was impressed by the University’s facilities and Flannigan, who originally contributed to developing the new microscope.

Seeing the right plans, facilities and personnel, Bates said, the company essentially donated the microscope to the school in exchange for the chance to see the equipment at work.

“They wanted the first of these instruments to be assembled and operated by the most competent people, which is our faculty, our grad students, our undergrads,” he said.