The federal prison in Waseca still resembles the school that was once considered a jewel in agricultural education.

Inmates still play basketball on the original floorboards of the school gym with the University of Minnesota-Waseca ram mascot painted at midcourt.

Had there been no barbed wire fences or sliding steel doors, the building could easily be mistaken for the University of Minnesota campus that it once was.

Waseca remains the epitome of small-town Minnesota, a rural farming community 75 miles south of âÄúthe Cities.âÄù But the culture in Waseca has changed since the campus closed in 1992.

When the school opened its doors Sept. 27, 1971 âÄî 40 years ago to the day âÄî the new, two-year college brought the town a sense of belonging and opened a world of opportunities to its residents.

But the Board of Regents voted to shut down the college under the justification of budget cuts just two decades later.

Closing the Waseca campus only saved the University $6.4 million âÄì a sliver of a percent of the UniversityâÄôs $1.6 billion budget in 1991, and a meager amount in relation to the economic impact and the âÄúbrain drainâÄù in the community triggered by the collegeâÄôs closing.

When the possible closure was announced, hundreds of Waseca students traveled to the Twin Cities campus to protest and poured into the stairwells of Morrill Hall before moving on to the State Capitol.

After the school disbanded, the Waseca community hit rock bottom.

Since its last class graduated in 1992, what used to be the school is now a prison, and what used to be the pride and glory of a community is now an empty void in the heart of Waseca âÄî a town of roughly 9,400 that is still searching for an identity.

An âÄòold dreamâÄô

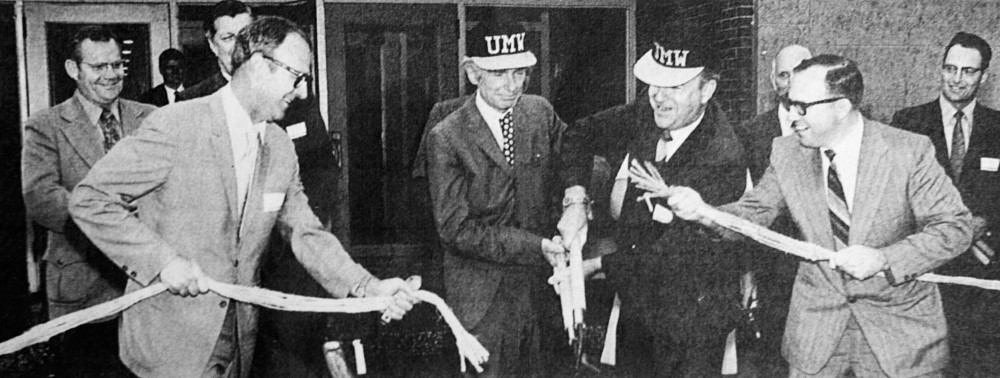

Edward Frederick still remembers the ribbon cutting ceremony 40 years ago.

âÄúThese are exciting times,âÄù Frederick said on that day. âÄúA new college doesnâÄôt get started every day. ItâÄôs a tremendous thrill to be working with a practical college [âĦ] one that you know will meet a need and serve agriculture.âÄù

Nearly a century has passed since the University first established a presence in the soil-rich town of Waseca.

The University purchased several plots of land in Waseca in 1912, and in the early 1950s it purchased several hundred more acres and established the Southern School of Agriculture, a boarding school for high school students that many Waseca supporters considered an âÄúold dream.âÄù

When the boarding school closed, the University of Minnesota-Waseca was born.

For 19 years, Edward Frederick was chancellor at Waseca, the highest position on campus and a role he held until he resigned in 1990.

Frederick, now 81 years old, works across the street from the prison as a senior fellow for the University.

âÄúI canâÄôt believe 40 years have gone by,âÄù Frederick said as he peered through the wall of metal chain-links that surrounds his former place of employment.

A death in the family

The low-security federal prison has a population of close to 1,100 inmates âÄî not much less than the collegeâÄôs peak enrollment number in 1985.

At that time, enrollment at the Waseca campus had boomed from less than 150 when it first opened. That number, however, dwindled down to approximately 800 in its final years.

A nationwide farm crisis in the âÄô80s likely contributed to the decrease in enrollment, said Ward Nefstead, a former professor at Waseca.

Overproduction forced prices down, and a grain embargo that was meant to punish the Soviet UnionâÄôs invasion of Afghanistan led to the loss of a major market for farmers to sell their goods.

Waseca never broke the thousand-student enrollment mark again, and by 1991 the University administration looked to the Waseca campus as a cause of its budget problems.

Hundreds of protesters greeted then- University President Nils Hasselmo when he traveled to Waseca in January, 1991 to tell them of his plan to close the school.

âÄúThis is a decision that my heart tells me not to do, but the facts say otherwise,âÄù Hasselmo said as protesters chanted âÄúHell, no, we wonâÄôt go!âÄù and âÄúHasselmo be on your way, agriculture is here to stay!âÄù

Some even called Hasselmo the âÄúgrim reaperâÄù of agriculture.

Opponents of the schoolâÄôs closing continued to show their support for the school. They sent scores of supporters to the Twin Cities campus.

Many sat in Board of Regents meetings while hundreds more picketed Morrill Hall and lobbied at the State Capitol.

Letters written to members of the board in opposition to the plan to shut down the school heavily outweighed letters in support of the its closure.

The college had survived a plan to phase out the school in 1973 by state legislators, but Hasselmo and the board succeeded in March of 1991, voting 10-2 to close the school that many had been seen as a leader in specialized education.

On paper, the motion to shut down the college saved the University $6.4 million, but in reality it saved them much less after factoring in the loss of student tuition and a voluntary termination program for faculty.

Closing the college was part of a $60 million reallocation plan that pumped millions of dollars into the College of Liberal Arts and the Institute of Technology, which Hasselmo said improved the quality of education at the Twin Cities campus.

In his University biography, Hasselmo said he considered the closing of Waseca one of the most difficult decisions of his nine-year presidency.

The decision to close the campus left a void in Waseca that many residents considered to be a death in the family.

Transition of a community

Jeanne Swanson, principal of the Waseca high school, was born and raised in town. She remembers playing on the collegeâÄôs football field as a kid, and working as a lifeguard at the schoolâÄôs pool.

She also remembers the benefits the school brought to the community.

Ph.D.-educated faculty and staff brought with them ideas and an emphasis on education that showed through the whole community.

New businesses arrived âÄî with an influx of more than 1,000 students, chains like McDonaldâÄôs came to town.

âÄúThe college was a big deal. It was progressive,âÄù Swanson said.

Most of all, the college offered a local alternative for students that wanted to stay and work on the family farm.

Instead of cutting their education short or having to leave their comfort zone, the students could then commute to school and return home to the farm by nightfall.

But when the school shut down, the future that the college had offered left as well.

From school to prison

In the wake of the schoolâÄôs closure, residents fought hard to keep the property as an institution of higher education, but the idea slipped away as a bill in the state Legislature to include the Waseca campus in the stateâÄôs technical school system was shot down.

Rumors soon suggested that a regional church office or an international school of aviation could be the next owners. The most serious interest, however, came from the Federal Bureau of Prisons, who had representatives from Washington, D.C., tour the facility in 1991.

The first prisoners arrived in Waseca in 1996.

The schoolâÄôs closing left a bitter taste in the mouth of residents who were angry with the University. But many residents were looking to move on.

The community was more upset with the University than they were with the BOP, Jim Tippy, the first warden of the prison, said.

In a public meeting held soon after the prison opened for inmates, Tippy remembers a packed house eager to hear what the BOP had to say.

A half-dozen vocal opponents sat near the front row, only feet away from where he was speaking. Everyone else had given up on the cause, but the protesters wanted to show the BOP that they werenâÄôt going to move on.

But each row in front and back of the protesters was empty.

After the Waseca campus closed, the University of Minnesota-Crookston transitioned a majority of its programs from two-year to four-year programs, including several in agriculture, Crookston spokesman Andrew Svec said.

Of the 17 programs that Waseca had offered, 14 were available at other colleges in the University system âÄî several of them at Crookston.

Meanwhile, in Waseca, a progress report presented to Hasselmo in 1991 noted the town as a âÄúcommunity that had hit âÄòrock bottomâÄô and was at a crisis state.âÄù

The confidential report spoke of a community fearing a âÄúbrain drain and the loss of a source of volunteerism in keys areas of the community.âÄù

âÄúIt was a very difficult time, a very tumultuous time,âÄù Mayor Roy Srp said.

From education to incarceration

The hallways of the former University of Minnesota-Waseca are fairly empty, as if class was in session.

Groups of female prisoners occasionally walk by, neither handcuffed nor followed by a guard.

Originally a prison for male inmates, it transitioned to a female prison in 2008 due to a growing female inmate population, prison spokeswoman Stacy Blee said.

A small research and outreach center is what is left of the UniversityâÄôs presence in Waseca.

The center holds an annual open house in mid-September as a promotional tool for the University.

âÄúItâÄôs to show [the residents] that weâÄôre still here,âÄù said Forrest Izuno, director of the research center.

One of the biggest events of the year in Waseca, the open house draws more than 3,000 visitors âÄì a third of the townâÄôs population.

The event nearly always brings back memories of the University of Minnesota-Waseca, but not all the memories are welcome.

For Waseca native Todd Selvik, a 2009 agricultural graduate from the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities, the move to the big city pushed him out of his comfort zone.

Selvik, whose father graduated from the agricultural high school, still wishes the Waseca campus was around.

Selvik said he believes he would have received a better and more focused education in agriculture production had he attended the Waseca technical school.

âÄúThe University doesnâÄôt have a strong agricultural production program,âÄù Selvick said. âÄúIt has agronomy degrees and business degrees in agriculture, but they donâÄôt have the type of education [that Waseca used to provide].âÄù

Many of his friends from Waseca who wanted to continue their education in agriculture opted to instead attend schools like North Dakota State University, Iowa State or Ridgewater College, a two-year technical school in Willmar, Minn.

Selvick is back in Waseca helping his father on the family farm after receiving his degree. He hears regret from residents and family who believe that the Waseca campus could still be something great today.

âÄúFrankly, what is this world coming to that you convert a college into a prison?âÄù said Robert Krumwiede, a former professor at Waseca.

Krumwiede, currently associate vice chancellor at the UniversityâÄôs Duluth campus, has been back to Waseca twice since the school closed. The first time, he drove within a quarter-mile of the fences and had to turn around.

âÄúI could not stand the thought of what had happened to the place,âÄù he said. âÄúItâÄôs the concept that education is fundamental to a better way of life and prison is a consequence of a bad way of life.âÄù