Minnesota has been the birthplace for a number of important creations, such as Scotch tape, the automatic toaster and now, miniature brains.

A University of Minnesota research team accidentally created the mini-brains while making diabetic islet cells. With more research and development, they hope the brain-like organoids will one day be useful in treating Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease.

While creating diabetic islet cells, researchers thought putting the stem cells into a Jell-O-like substance might make more cells faster. They were surprised to find that this actually created mini-brains.

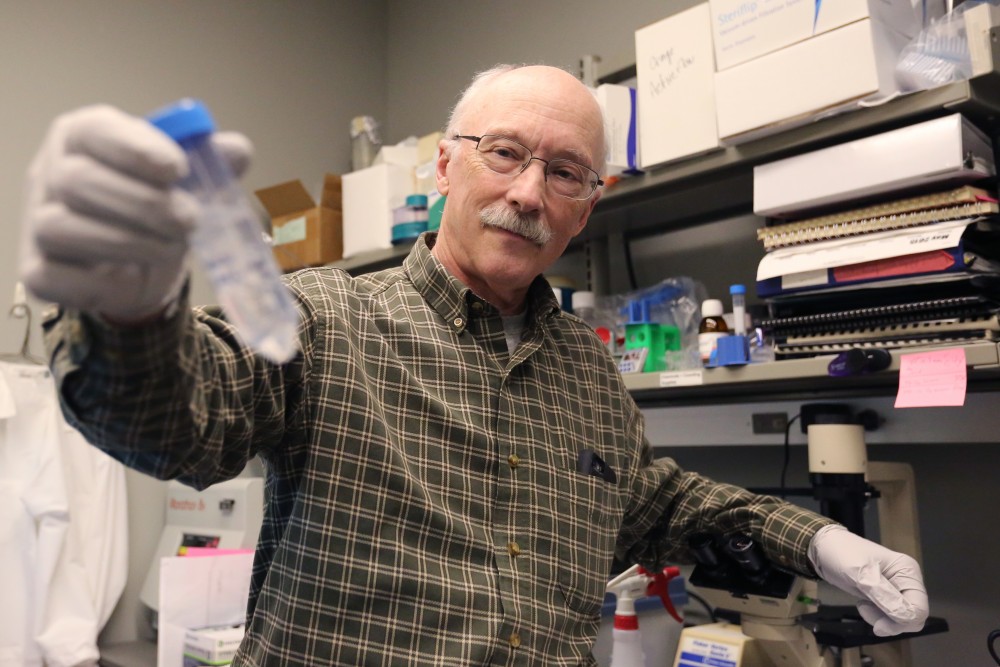

“The trick was to recognize what we had,” said professor and research lead Dr. Timothy O’Brien.

These organoids were created from sample cells, either from a donor or an individual with a neurodegenerative disease, that were genetically modified to be virtually identical to an embryotic stem cell, he said.

Even though these organoids have been named mini-brains and act like a human brain in specific ways, they do not have all the components of a human brain, O’Brien said.

They can’t think on their own and lack certain blood vessels and immune cells, said professor and VFW Endowed Chair in Pharmacotherapy for the Elderly Ling Li.

Since researchers cannot sample brain tissue from a living person, Li said the mini-brains could be used to provide an accurate experimental model to study the human brain.

“This will give us [the] opportunity to develop a more human-like model,” Li said.

Pharmaceutical drugs could also be tested on these mini-brain models since they are closely resemble a live brain, O’Brien said.

O’Brien said he hopes to create accurate models of the brain to test treatments for Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease.

Researchers can also use these organoids to create individualized treatments for people with Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s. By taking a skin sample from a Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s patient, researchers can create mini-brains with the individual’s exact genetic make-up and inject the organoids into the parts of the patient’s brain to regenerate damaged cells, O’Brien said.

The mini-brain organoids have been injected in rats to test their effectiveness. O’Brien said the next step is to test them on primates, and if that’s successful, start a clinical trial with humans.

Current research for Parkinson’s disease treatment, which affects about 1 million Americans, is focused on finding ways to stop or slow the degeneration of dopamine in the brain, said Rose Wichmann, manager of Struthers Parkinson’s Center in Golden Valley.

Most people with Parkinson’s use medication to restore the lost dopamine, but this is not a cure, Wichmann said.

Similarly, people with Alzheimer’s disease — about 5 million people in the U.S. alone — take medication to slow the symptom progression, but memory loss is still inevitable, said Katie Roberg, program and education manager for the Alzheimer’s Association.

Even though the mini-brains have promising research and treatment applications, they’re not perfect, Li said. As technology improves, researchers hope to make the mini-brains more representative of the human brain.

Plus, more research is needed, and the organoids are still years away from potentially treating Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, O’Brien said.

“I’m very excited and hope that this keeps working out. Everything’s so far, so good,” O’Brien said.