By day, Andrew Kozak, a veteran Minneapolis politico, makes a living making voices heard at the State Capitol.

No, not your voice but voices like those of RAI Services, a consumer products company based out of Winston-Salem, North Carolina. You might know RAI Services for its best-selling consumer products like the Newport, Camel and Pall Mall cigarette brands. Along with RAI Services, Kozak is a registered lobbyist in Minnesota for American Express, Dunbar Development and Flint Hills Resources, LLC, the oil refining company owned by the politically influential Koch family.

By night, Kozak is one of 15 commissioners at the political retirement home known as the Minneapolis Charter Commission. Today, the Commission is chaired by a mergers and acquisitions lawyer and populated with only three people of color in a city that is 40% nonwhite.

Kozak and many of his fellow commissioners would never be elected for any office, so they sit on the Commission through appointment by a judge. It’s how the future of police reform is now in the hands of a tobacco lobbyist, the treasurer of a pro-business PAC — which spent $275,000 of business interest money in the last city election — and a former chair of the Republican Party of Hennepin County, among others.

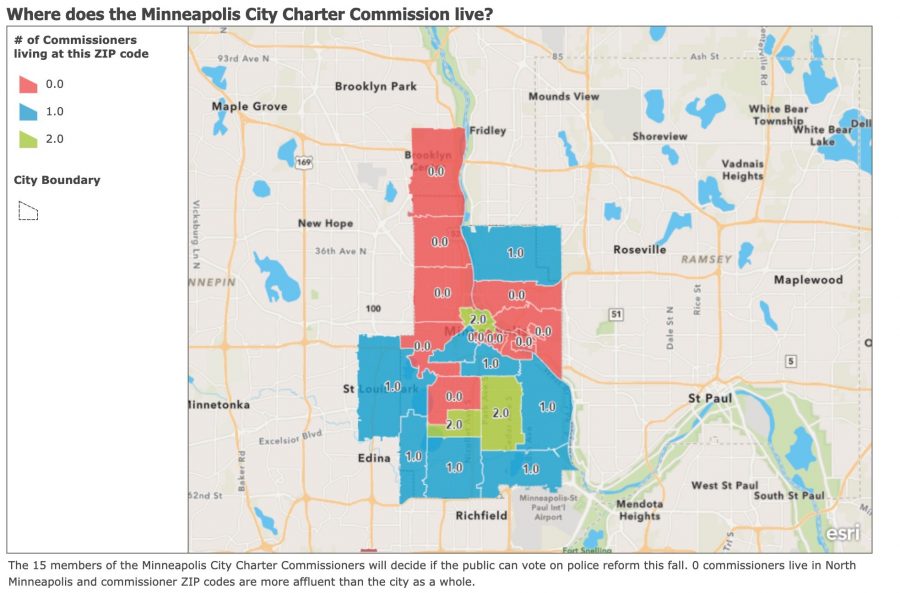

Most telling is that none of the commissioners live in North Minneapolis, the home of about 80,000 Minneapolitans, two City Council wards and the historic heart of Black Minneapolis. Only one commissioner lives in Northeast Minneapolis, while every other commissioner lives in either South Minneapolis or Downtown. Five commissioners alone live in Southwest Minneapolis, the richest and whitest portion of the city.

The Commission is normally a low-key affair, reviewing amendments to the city charter — basically the city’s constitution — and offering nonbinding recommendations. Even by the standard of most city commissions, its meetings and public hearings are sparsely attended and were not even broadcast live until this summer. (You can watch future Commission hearings here.)

However, in its response to the ballot question and subsequent police reform amendment that the City Council has put before it, the unelected Charter Commission has shown that it is profoundly undemocratic and out of touch.

In place of the police, the City Council’s proposed amendment would establish a Department of Community Safety and Violence Prevention, which would contain a division of police officers. It would put the police and the larger public safety department firmly in the City Council’s control, unlike today, and give the council the opportunity to take a year to study and implement its voter-backed vision of public safety. The Charter Commission is legally required to give a recommendation on the amendment, but it’s an opinion that can be ignored by the Council.

Crucially, the Charter Commission can opt to take an extra 90 days, on top of the 60-day deliberation period, to decide its opinion on Aug. 5, meaning that it would overshoot the Aug. 21 deadline to appear on the November ballot. In one of the most important election years in U.S. history, and one certain to have high turnout, Minneapolis voters would have to wait until 2021 to vote on police reform.

To compare, Minneapolis had a voter turnout of 79% in 2016, compared to a turnout of 42% in 2017. That is a huge difference in turnout that the Commission and Council are very aware of. The ballot question would lose steam and be voted on by fewer voters, and those voting would skew affluent and white. It’s a disingenuous opposition strategy that the civil rights movement often faced from white political leaders: not now, but later, we promise.

Robin Garwood, policy aide to Council member Cam Gordon, said the power to take more time is one that the Charter Commission has used as a pocket veto. The Commission previously killed a police reform amendment Gordon had proposed in 2018.

“That’s just inappropriate. It’s not what they should be doing,” Garwood said. “It is the same thing as a filibuster.”

It’s a filibuster that stings especially badly because the Commission is an unelected body and collection of political castoffs that the old DFL machine thought we would forget about. In a city where many councilors only last a term or two, multiple Charter Commissioners have served more than a decade, with some like Chair Barry Clegg and Jana Metge having served 17 and 15 years so far, respectively.

Another commissioner, Dan Cohen, has been on the commission since 2009. In 1969, Cohen ran for mayor and lost to a cop, Charles Stenvig, who pledged to crack down on “racial militants,” criminals and student protesters. Undeterred, Cohen ran again in 2013 and lost and now writes crime novels about police corruption. Surprisingly, he is the most conservative Commissioner on the issue of police reform.

While some commissioners are guests who have overstayed their political welcome, others, like Kozak, are permanent interns for power. They won’t ever get the job — who would hire someone who shills for tobacco companies? — but they’ll try.

For example, local political blog Wedge Live found that one commissioner, Matt Perry, was the treasurer of a political action committee called “Minneapolis Works!” that worked with another Republican PAC to funnel business money into city elections. In 2017, Minneapolis Works! spent $275,000 trying to stop challengers to the left of then-city councilors, like conservative Democrat Barb Johnson, who ultimately lost to Phillipe Cunningham, a current leader of the police reform efforts.

“This thing where they misuse the clock to act as the gatekeeper to the ballot is not the way that the system was designed to work,” said Garwood.

Garwood said that if the Commission realized it wasn’t representing the community, it should say, “It’s not my job to act as the gatekeeper for the ballot. And, if it was going to be the job of this body, this body would have to look a lot different than it looks right now.”

In this way, the Charter Commission is a vestige of old Minneapolis politics: white and opaque. It has no place in our modern democracy. If the Commission’s filibuster succeeds, then it is an act of theft from the people of Minneapolis. The people deserve to have the question of police reform answered on the ballot, and not by an obscure, unrepresentative Commission. They deserve the ballot question this year when all their neighbors will vote too and not next year when less than half the city votes.

Meyer

Dec 9, 2020 at 7:57 am

I wrote a lengthy response to this at the time. Where did it go?