Minnesota’s COVID-19 response peaked on March 25, when Tim Walz issued the stay-at-home order that resulted in the closure of all non-essential businesses and public accommodations, including restaurants, government buildings, schools and gyms. After gradual reopenings, most operations reached at least 50% capacity on June 10. During the 87 days between, Minnesotans were instructed to avoid large group gatherings, stay home, and limit travel whenever possible. For most, general safety precautions during the pandemic have been inconvenient. But for the 11,000 homeless adults, families, and children in Minnesota, those same safety measures have proven extremely difficult to uphold.

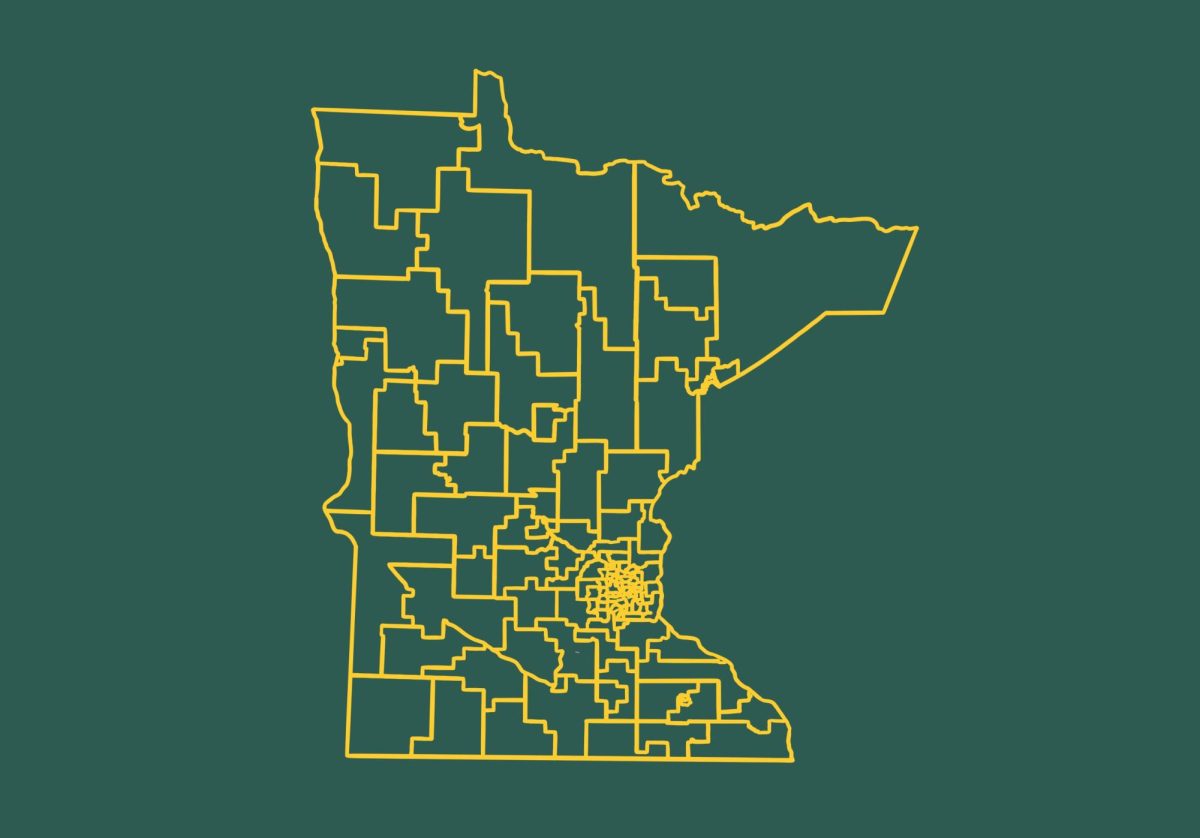

A study done in 2018 identified at least 4,000 individuals who met the federal definition of homelessness in Hennepin County alone. The heavy implication of modern homelessness is evident in recent data, which reports that 48% of homeless individuals suffer from a chronic health condition. Pre-existing conditions in combination with communal housing, shared facilities, reliance on public transportation, and minimal access to services like hand-washing stations put the homeless community at increased risk for transmission of COVID-19.

On March 26, the Minnesota House of Representatives voted to allocate financial assistance across the state in response to COVID-19. Among other emergency allotments, the bill set aside $26 million to assist people who are homeless.. Since then, the funds have been used to stockpile shelter sanitation resources and provide on-site medical staff. The bill also provides short-term motel vouchers for those experiencing homelessness who are exposed to the virus, and, in anticipation of local unemployment, temporarily increased housing support rates for low-income senior citizens and adults with disabilities.

Not everyone experiencing homelessness considers shelters to be a viable option, though. Many shelters implement ID requirements, substance possession rules, pet restrictions, and capacity limits that dissuade homeless people from their services. Additionally, members of the homeless community have cited theft and violence in shelters, which may be why 35% of people who are homeless remain unsheltered even during winter months.

To exercise personal autonomy, many people who are homeless turn to encampments, like the one at Powderhorn Park, which exceeded 500 tents this summer. In August, the Powderhorn encampment was forcefully cleared by action of the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board after multiple reports of crime and drug use. The MPBR intends to limit city park encampments to 20 or less parks, and less than 25 tents per park, severely diminishing the number of people legally permitted to stay there. Campers will also be required to have a permit. These actions leave hundreds of vulnerable people homeless, and directly conflict with the CDC’s recommendation not to displace individuals in encampments.

Although the global pandemic may have catalyzed conversations about the well-being of the homeless population, the community had been dealing with disease, limited access to healthcare, and community safety issues long before COVID-19 was breaking news. Until Minneapolis achieves affordable housing, healthcare, and a diverse selection of high-functioning welfare programs, public health issues will continue to have an infinitely greater impact on its most vulnerable populations.