Weisman Art Museum faces criticism after delaying repatriation of Native American objects for 30 years

Graduate anthropology students are advocating for the Mimbres Collection’s return to affiliated tribes in New Mexico.

Image by Emily Pofahl

The funerary objects have been housed at the Weisman Art Museum since 1992.

The Mimbres Collection at the Weisman Art Museum has a long and complicated past.

First excavated by anthropology professors and students in the 1920s, the collection of human remains and burial belongings was housed at the University of Minnesota before being transferred to the Weisman, where it remains today.

Mimbres bowls, characterized for their painted designs and a round hole in the center, were used in burials in 11th century New Mexico among a variety of Pueblo tribes, including the current-day Hopi Tribe, Pueblo of Zuni and the Pueblo of Acoma.

Despite repeated attempts by affiliated tribes to return the collection to New Mexico, the funerary objects remain at the Weisman. Under a 1990 federal law, institutions that receive federal funding must create an inventory of any Native American cultural objects or funerary remains as a part of the repatriation process. The University and the Weisman have come under fire by Native American communities, anthropologists and the Minnesota Indian Affairs Council (MIAC) for their delay of inventory.

Now, about 90 years after the excavation, University anthropologists and archeology students have been working to compile an inventory of the collection to return objects to affiliated tribes who claim descent in New Mexico.

In mid-September, a letter was drafted to the University on behalf of all the graduate students in the anthropology department. Their message was clear: repatriation is not only warranted, but essential to address the “historical extractive and unethical practices of our department.” The letter cites the history of the collection and contextualizes the University’s role in larger structures of oppression against people of color, especially in light of the police killing of George Floyd.

An enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, fifth-year anthropology student Elan Pochedley said his involvement as a co-author of the letter was especially personal.

“Potawatomi people and nations have also been affected by these practices of exhuming, looting, and collecting Indigenous bodily remains and funerary objects for the benefit of institutions of higher education,” he said in an email to the Minnesota Daily.

“In a moment when questions of racial justice and institutional accountability are of the utmost importance to address, we are not interested in erasing the Department of Anthropology’s institutional legacy as it pertains to the Mimbres excavations and the looting of Indigenous graves.”

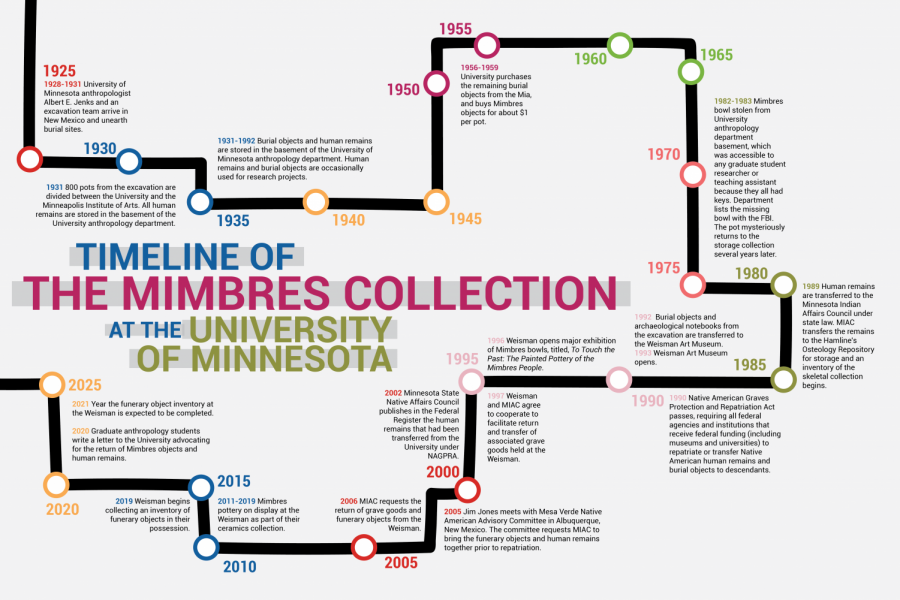

A timeline of the Mimbres Collection at the University

The Mimbres Collection has a long history, stemming from a 1928 archaeological expedition in the Mimbres Valley, New Mexico led by Albert E. Jenks, the founder of the University anthropology department. In a collaboration with the School for American Research and the University of New Mexico, and with a sponsorship from the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Jenks along with several other graduate and undergraduate students unearthed burial sites for over three years.

Jenks returned to Minnesota with the human remains of about 190 people and almost 3,000 painted bowls, ceramics, animal bone tools, jewelry and other objects that were buried with them.

Both the human remains and burial objects were stored in the basement of the anthropology department until 1992. In 1989 under state law, the University anthropology department transferred all the human remains identified as of American Indian descent to MIAC to await repatriation efforts.

The human remains are currently housed at Hamline University, which has an agreement with MIAC to store and take care of the remains until they are returned. As the Weisman Art Museum was being built, the burial objects were relocated there for safekeeping and storage.

Under the Federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), which passed in 1990, all institutions that receive federal funding, including museums and universities, must engage in repatriation efforts with affiliated Native American peoples.

Along with a compiled inventory, each museum and federal agency is required to send a summary with a general description of the sacred or funerary objects in its possession to any Native American tribe or organization who may be affiliated with the items. This summary serves as an invitation for the tribes to consult with the institution, and gives them an opportunity to request the return of these items.

In the summer of 2019, the Weisman, which had initially only submitted a general summary, began collecting an inventory of the funerary objects in their possession.

This work was delayed in part by a miscommunication about whether MIAC was designated a federal entity that needed both a summary submission and a comprehensive inventory, said former Weisman director Lyndel King, who served at the Weisman from 1981 to June 2020. King said to her knowledge, the museum believed they were compliant with NAGPRA, and said their noncompliance was an “honest mistake.”

MIAC has long criticized King’s leadership, and in a resolution in June wrote that the University had intentionally failed to comply with NAGPRA for over 30 years, despite repeated demands of repatriation and action from the Weisman.

In recent years, Native American tribes with cultural affiliation to the Mimbres objects and remains have requested both the human remains and funerary objects be returned together, so as to properly rebury their ancestors.

The process of repatriation

Kat Hayes, an associate anthropology professor and director of the Race, Indigeneity, Gender and Sexuality Studies Initiative at the University, has also been heavily involved with the repatriation efforts by providing research and directing the completion of the Weisman’s inventory. Hayes said in many circumstances it can be challenging to establish cultural affiliations with burial objects from thousands of years ago due to patterns of migration over time.

But based on the evidence they have, she said it is clear to see that many, if not most, of Pueblo communities are descendants of the Mimbres people. Detailed archeological field notes from the 1928 to 1931 expeditions indicate precisely where the burial objects were taken by Jenks, and oral traditions relay migration patterns that have established ancestry in these areas, Hayes said.

Former University graduate student Melissa Cerda has been looking into University compliance with NAGPRA for years.

As a senior cultural resource specialist for MIAC, Cerda said the process has required something similar to detective work, sorting through and digitizing old archeological excavation notebooks and fading collection records to trace where objects came from and how they came to the museum.

While completing the inventory, Hayes, Cerda and a couple other students had to formally request the notebooks and materials from the Weisman be scanned so they could use them, as the Weisman only made the field books available to the researchers for an hour or so at a time, Hayes said. Hayes also said she had to remind the Weisman that it was within their rights to access the information based on an agreement with the anthropology department.

At Hamline’s Osteology Repository, Desiree Haggberg is the supervisor who oversees MIAC’s skeletal repository. As part of the cataloguing required of NAGPRA, Haggberg gathers as much physical evidence about the bones as possible, accessing characteristics like sex, age, height and trauma to the skeleton. Haggberg said some of the human remains taken from the Mimbres Valley are full skeletons, but most are partial, with only one or two bones from a single person.

“The vast majority of the human remains, we don’t know what happened to them,” said Matt Edling, the lab and collections manager of the University anthropology department. “[Jenks’ excavation team said] they excavated them, but they never came back to the University of Minnesota and were never cataloged into our collections … Who knows what happened to them? We don’t know.”

Part of Edling’s role in the repatriation process is tracing what happened to all the funerary objects and human remains collected by Jenks and his team. Some objects have been traded or gifted to other art museums or anthropology departments around the country. Others were rumored to be stolen, taken from the anthropology basement and sold.

Edling said in an email to the Minnesota Daily he believes this issue should have been investigated years ago, when MIAC first contacted the Weisman, and “definitely after the Weisman received an official request for repatriation from the Hopi Tribe in 2014.”

Despite having original field notes from the excavations in their possession that stated most objects were associated with funerary contexts, in a 2004 letter obtained by the Minnesota Daily, King wrote to the Hamline Osteology lab that, “I understand … that the intent is to claim repatriation for bowls to these groups mentioned in the proposal. We are not aware of any basis for such a claim for repatriation under NAGPRA.”

Lasting effects

A former NAGPRA representative for MIAC, Jim Jones was involved with the fight for repatriation of the Mimbres collection at the Weisman for over two decades. He said the work has taken a significant toll on him, and eventually he had to stop doing repatriation work.

“The University of Minnesota and the Weisman and everyone has to get on board and do the right thing,” he said. “These people that are associated with those remains from the Southwest, whether it’s the Pueblo communities, the Zuni, the Hopi — the communities down there deserve their relatives back and anything that’s associated with them.”

Andrea Carlson graduated from the University in 2003, and said she has been fighting against the showing of Mimbres objects since she was an undergraduate student. As an Ojibwe artist, Carlson said working with museums and institutions with ethnographic collections on display puts Native artists in a unique position.

“It feels different to you. It hurts you in a different way,” she said. “There’s part of me that wishes I could just work with a museum. That way, I didn’t have to question whether or not they had my body or the bodies of my people.”

In 2018, Carlson was invited to be on an advisory board for the Art Institute of Chicago. The museum was months away from showing a collection of Mimbres pottery donated from a private collector and wanted to get advice from several Native American people on how to proceed. Despite Carlson and the four other Native people on the board advocating strongly against the showing, the museum continued moving forward before postponing the show indefinitely right before their expected opening.

Many museum curators perceive and display Native American pottery, cultural objects or burial belongings as beautiful works of art that should be accessible and shared through the medium of a museum, but they do not have the authority to make those claims, she said.

“I’m so used to hearing how beautiful our grave objects were,” Carlson said. “Just because they’re beautiful does not give a non-Native person the right to put them on display.”

Serving as a reminder of the damage still unfolding, over the summer the Weisman found a tooth, several bone fragments and two cremation bundles in the museum’s holdings that were previously uncatalogued by the museum. The remains were immediately turned over to MIAC and taken to Hamline, but the Weisman acknowledged the damage it caused.

“This discovery was, of course, particularly disturbing and distressing, and it underscores the importance of completing the full inventory of the Mimbres materials,” wrote the Weisman in an informational FAQ about the collection on their website. “A complete inventory is absolutely crucial to ensuring that these human remains and all the affiliated cultural materials are properly identified and cared for with the respect they deserve.”

The museum said their full inventory of the Mimbres funerary objects should be complete by March 2021, assuming pandemic-related University closures do not delay the process. At the end of August, the University also started an advisory committee composed of Native American scholars and several other University professors. The committee will consult with tribal affiliates and advise University leaders in decisions related to the collection.

As a Korean Native American artist who identifies as a descendent of the Mimbres Valley people, Debra Yepa-Pappan said she gets frustrated working with art museums and institutions who want to make the determination of what objects are culturally significant enough to display. Ignoring the wants and needs of Native American people contributes to a power dynamic where largely white-led institutions then control their history and narrative.

“If it’s ultimately significant to Pueblo people, then let it be ours,” she said. “[Mimbres pottery] are made beautifully for a reason, not for us to look at. These are materials that were supposed to remain with those people they were buried with. And it’s for them, not us.”