With the race to distribute a COVID-19 vaccine on the horizon, the University of Minnesota has established a national organization to help mitigate the spread of the virus in migrant communities.

Based at the University, the National Resource Center for Refugees, Immigrants and Migrants (NRC-RIM) will work with state and local health departments across the country to develop and disseminate better practices for COVID-19 control and prevention in communities that need it. Key goals include fighting disinformation, destigmatizing healthcare and eliminating barriers for refugee, immigrant and migrant populations.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the International Organization for Migration awarded more than $5 million to help create the center, which is a collaboration of multiple departments and colleges across the University.

“It’s been really exciting so far,” said Erin Mann, NRC-RIM program manager. “There’s a lot of energy and urgency with getting the project up and running in order to get some resources and materials and tools in the hands of state and local health departments.”

Mann works within the University’s Center for Global Health and Social Responsibility, which houses NRC-RIM.

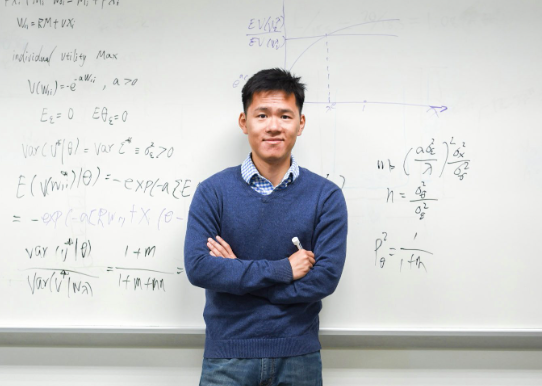

Dr. Shailey Prasad, a professor in family medicine at the University and co-lead of NRC-RIM along with Dr. William Stauffer, said this work will involve creating accurate communications between healthcare professionals and the communities they intend to serve. The center also aims to improve culturally relevant practices and training for those health professionals.

“I would make the case that we need to approach these communities wherever they are,” Prasad said. “In some of the communities, there was more of a communal sense of participation in programs. [We consider] how we can tap into that as a way to approach healthcare messaging. Those are the things that we will be looking at.”

Prasad said the center is especially necessary because of the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on many refugee, immigrant and migrant communities. Although the CDC has not yet identified the full scale of this impact, a growing body of evidence shows that various socioeconomic factors lead to poorer health outcomes in these communities across the U.S.

These factors include: attitudes toward healthcare, density of housing, access to housing, language barriers, working jobs that do not emphasize COVID-19 precautions, distrust and fear of government authority and a predisposition to underlying medical conditions.

Prasad said he thinks the next phase of the work includes vaccination strategies, which would involve tackling issues like vaccination barriers and hesitancy in refugee, immigrant and migrant communities.

Vaccine hesitancy has hit close to home before. In 2011 and 2017, the Somali community in Minnesota experienced large measles outbreaks that have been partially linked to vaccine hesitancy. This was due in part to widespread misinformation fostered by a 1998 study linking certain vaccines to autism.

The study has since been disproven, and almost all ensuing theories have been thoroughly debunked by doctors and scientists. However, it has had a lasting impact on attitudes toward vaccinations — especially those in migrant communities in the United States.

Ahmed Mussa, community health coordinator at the Brian Coyle Center in Cedar-Riverside, said outside efforts to curb wariness around vaccines would be largely ineffective in communities like the one where he works without the assistance of trusted leaders.

“It has to be from someone they know and trust in the community — an elder or an imam or someone who has worked there and knows them,” he said. “It needs to be someone who can clearly say, ‘Here is what it is; here is what it does.’ Before anyone else comes in, they need to listen to people in the community, really hear them, and address those concerns first.”