“We should be all covered here for close, does anyone want to clock out early?”

I learned to remain quiet longer than others when my manager asked this question at the end of slow days with a full staff. Eventually, around the point that protracted courtesy turns to awkwardness, some other student worker would chime in, “Yeah, if no one else wants to, I can go. I have to get to my other job.” The volunteer would pack up their stuff to head out, and I would stay the extra 30 minutes to close up before retreating home to my homework or some social outing.

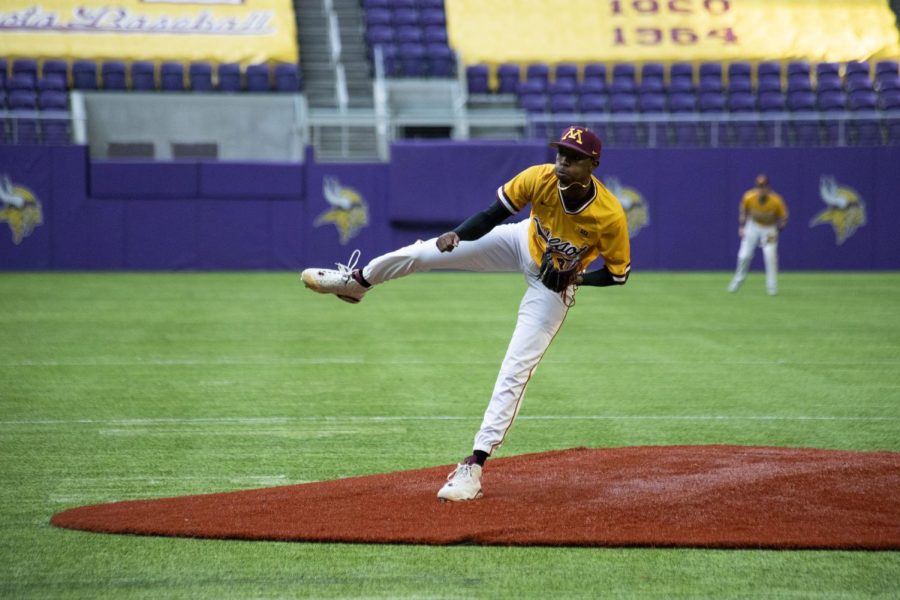

During my year and half tenure at the University of Minnesota bookstore, I came to be intimately acquainted with the difficulty faced by students with less financial support than myself, the intense workload they endure, and the resourcefulness they display in spite of what seemed to me to be few opportunities for assistance. In sharp contrast to the experience of myself and most in my personal friend group, who have comparably few commitments, many of the students with whom I worked were in constant states of movement, shifting attention from one occupation to another in a manner that would have seemed desultory had it not been, for them, necessary. When I went home at the end of the day to take care of chores or school work, some of my fellow coworkers were out working somewhere else.

I remember one occasion during which — not without some ignorance — I expressed surprise that the kid I was talking to worked three jobs that semester along with his course load. As the conversation proceeded, he told me about being a first generation college student, and that his parents and the scholarships he had applied for and received could only do so much. He told me about handling his own expenses while balancing course work. When I asked him about how he manages to complete school work and pay his way through college, he told me that he did his best, but that academic excellence came second to the necessity of paying for the opportunity to study at all.

There are many benefits to a University job, including a healthy work environment and flexible hours, but I would not recommend them to someone looking for a lucrative position or even, for that matter, to make a decent buck. As of April 7 of this year, the University of Minnesota Office of Human Resources reports that the minimum wage for student jobs was $10.08, and the average wages (depending on job family) range from $11.03-$12.18. Critically, this data reflects student wages systemwide, i.e. the averages of wages across all campuses.

The University’s system-wide minimum wage is in accordance with Minnesota law, which has set the state-wide minimum at $10.08. Because the University system is technically owned and operated by the Minnesota State Government, it is exempt from the Minneapolis Minimum Wage Ordinance. As a result, despite the historic ordinance that is set to incrementally raise the city’s minimum wage to $15/hr by July 1, 2024 (July 1, 2022 for businesses employing over 100 workers), student workers on the Twin Cities campus are paid less than what their own city has deemed equitable.

The current city-wide minimum wage in Minneapolis is $12.50 for small businesses and $14.50 for larger ones. Though it is acknowledged as a state-run public institution, the University functions as a large business in many capacities. Even if it follows Minnesota rules for paying full-time students that work part time (a case which allows businesses to pay 85% of the minimum wage), the Minneapolis students would be deserving of $12.36/hr according to their city, and students in other municipalities would earn as little as $8.57/hr.

The issue, then, is technically not a legal one. The University is allowed to pay students a minimum wage that reflects the state law rather than the city’s law. But the view from the ground is incongruous with the legal justification. The choice to apply the same wage rules broadly like this misses the fact that the populations of different cities and counties have very different experiences. The very fact that both Minneapolis and St. Paul have taken minimum wage into their own hands reflects a need that is specific to their constituency, and that will likewise have specific effects on the economy of their city, further differentiating the experiences of their population from those in another municipality.

Raising this campus’ minimum wage is not going to completely eliminate all of the difficulties faced by some of my former coworkers, but it could certainly help. More pay may mean fewer hours, which in turn means more time freed up for studying, which, as we shouldn’t forget, is supposed to be the reason we come to higher education in the first place.

Of course, more assistance may be needed by certain students in the form of scholarships, financial aid, etc., but asking a campus to comply with the minimum wage ordinance of the city it occupies (even if not legally obligated to do so) seems like a relatively easy decision that acknowledges the lived experiences of the students that not only study here, but who offer their time and effort to the University through work.

I took the job at the bookstore because I wanted to find a kind community and to have some extra spending money in my pocket. I enjoyed my time there quite a bit; the atmosphere is forgiving, generally upbeat and the employees and managers are always friendly. However, when my life got busy, I decided to go on call. I could afford to work by picking up shifts that others had to drop if it meant making sure my academics did not suffer. And this is a crucial difference between myself and many other student workers. Sometimes, academic success is contingent on whether or not your pockets can manage a dropped shift here and there. When you are paid less than your city’s minimum wage, the chances that you can manage this are certainly lower. The Twin Cities campus is not legally bound to follow the Minneapolis Minimum Wage Ordinance, but nor is it bound by law to stay down at the state-wide minimum. It is in the interest of the mental and financial health of the student workers that they are paid what their city has deemed a livable wage, and it should be, in turn, in the interest of the University.

A Gopher

Sep 15, 2021 at 6:07 pm

Higher pay from the UMN system = higher tuition. When I attended the UMN my base pay was $6.75/hour. It helped me get the lab experience I needed for my career, but it wasn’t enough money so I got a job driving limos for $25/hour. Students need to be creative if they want greater cash flow than simply stating they need a raise from the U. Academic pay scale will always lag behind private sector pay, period.

UMN0001

Sep 15, 2021 at 4:45 pm

I worked for the bookstore in during the 2011-2012 year. Base tuition was $12,288 and my wage was $8.25/hr. Base tuition last year was $14,760 and minimum wage is $10.08. Seems fine to me. Plus students now are at an advantage with how cheap interest rates are on student loans.

I lived in a crappy house in Como, worked 25-30 hrs. per week at my student job, rode the bus or biked to save money and I did just fine at $8.25/hr without help from my parents. You make your money working 40-60 hours during the summer so you can work less if needed during the school year.

Students go to college and expect to eat out every meal, drink all weekend, pay for cable, go on spring breaks, live in fancy apartments, park a car on campus, have student football, hockey & basketball tickets, etc. Sorry, but if you are struggling, there are luxuries you can cut back on like those in every class before you.

Richard Turnbull

Sep 15, 2021 at 11:24 am

This is not a math equation, and your assumption that it is is a “Category Mistake.” You can google it, Professor Ryle is still worth reading. Most of the ordinary language and logical positivist philosophers are well worth studying, if only so you can try to refute them. Have at it, Mary P!

It’s also lazy propaganda. You might as well say, “Justice is whatever is the interest of the stronger,” along with Thrasymachus in Book 1 of Plato’s Republic, in answer to Socrates, and at least elevate the tone of your implicit attack on progressive rights for working students!

“Labor creates all wealth.” — Abraham Lincoln

Mary P

Sep 14, 2021 at 1:56 pm

Living workers = livable wage

brn

Sep 14, 2021 at 11:35 am

This is a tough one. When I went to school, I worked at the school, helping others with their coursework. I don’t recall the pay (it was a very long time ago), but it was definitely low. Looking back, I’m OK with it. I learned a lot about helping others and it provided time for me to work on my own studies. Overall, a good experience.

But then there’s the bookstore. I don’t know about the UofM bookstore, but ours was privately owned, for profit, and was more than willing to use their campus monopoly to reap in the profits. Such an organization should be forced to be wage competitive.