Cars lined up on Cedar Avenue honked at two people vandalizing the Imam Shafi’e mosque on Sept. 8 in broad daylight.

“I asked them, ‘Why are you spray painting the mosque?’ and they ran and threw the spray paint can,” neighbor Mohammed Abdi said. “I followed them and saw their car … Once I caught his license plate, he started covering his face, went in his car and drove away.”

The vandals appeared during the 7 p.m. daily prayer, which often is the busiest time at the mosque, according to community leader Abdirizak Bihi.

“They know that what they’re doing is wrong … and this one on Cedar Avenue was very daring,” Bihi said. “[It was] during the daytime, their faces were scary, they were intentional. We didn’t figure out what [the graffiti] stood for.”

As the anniversary of 9/11 approached, residents found graffiti on the walls of either Imam Shafi’e or Darul Quba mosques on almost a “daily basis,” Bihi said. Imam Shafi’e speaker Abdalaziz Mohamed said they have experienced a spike in vandalism during the weeks prior to Sept. 11, but leaders did not track how many times the buildings were defaced.

The American Civil Liberties Union tracked nationwide anti-mosque activity from 2005 to May 2021, finding 10 incidents in Minnesota since 2012. In November 2019, a vandal shattered a glass door of Salaam mosque in northeast Minneapolis, which is the most recent incident logged by the ACLU as anti-mosque activity.

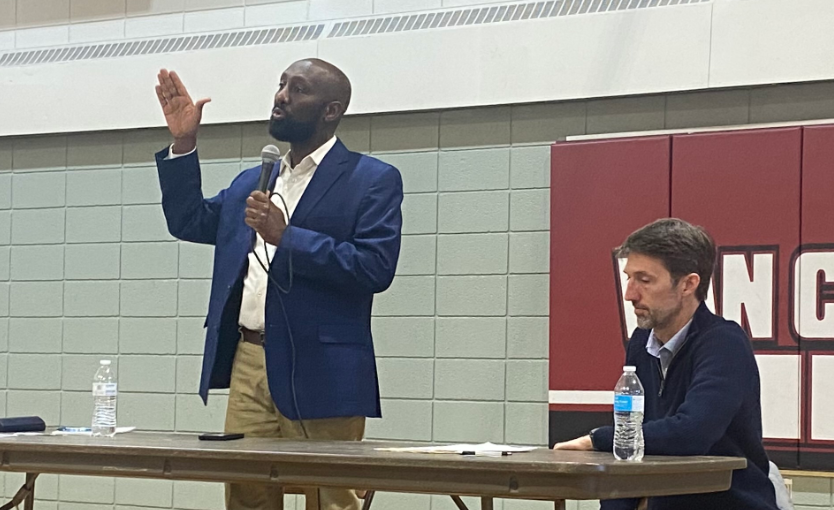

Minneapolis Ward Six Council Member Jamal Osman said he spoke with mosque leaders and neighbors after the incident, though he said the graffiti did not contain any hateful or discriminatory messages.

“It’s not Islamophobia, it’s not targeted because of religious reasons,” Osman said. “These tags are any other problem Minneapolis has. They were not specifically targeting this neighborhood because it has a mosque.”

Imam Shafi’e speaker Mohamed said he is unsure if the incident was motivated by bias, but said other residents see it as a threat.

Impact on businesses

KJ Starr is the interim executive director of West Bank Business Association (WBBA) and her husband owns The Wienery. She said vandalism became more frequent during the protests following the murder of George Floyd in the summer of 2020.

Starr said she believes that people found it easier to vandalize businesses when they closed due to the pandemic lockdown. Now that neighborhood businesses are back open, she said WBBA is able to work harder to prevent vandalism, though it is still more prominent than it was before the pandemic.

The Red Sea owner Russom Solomon said he also noticed more vandalism and graffiti within the last two years. He said that he put a mirror on the outside of his building to deter people from painting it.

“You have to have security watching your building to prevent this, it’s gotten so bad,” Solomon said. “It’s really sad.”

Starr said the cost of recovery depends on the extent of the damage. She said most graffiti can be painted over, but if a vandal uses acid-based paint, “you can’t do anything about that.”

She said recovering a building after windows or other parts have been destroyed is more expensive, but WBBA often helps businesses cover the costs. Either way, Solomon said dealing with vandalism is “a headache.”

“If you want to restore the original look of something, it requires a lot of money, a lot of effort, a lot of time,” Solomon said.

Painting solutions

After the daytime vandalism of Imam Shafi’e, Osman said mosque leaders told him they were open to putting art on the targeted wall of the building to prevent future graffiti.

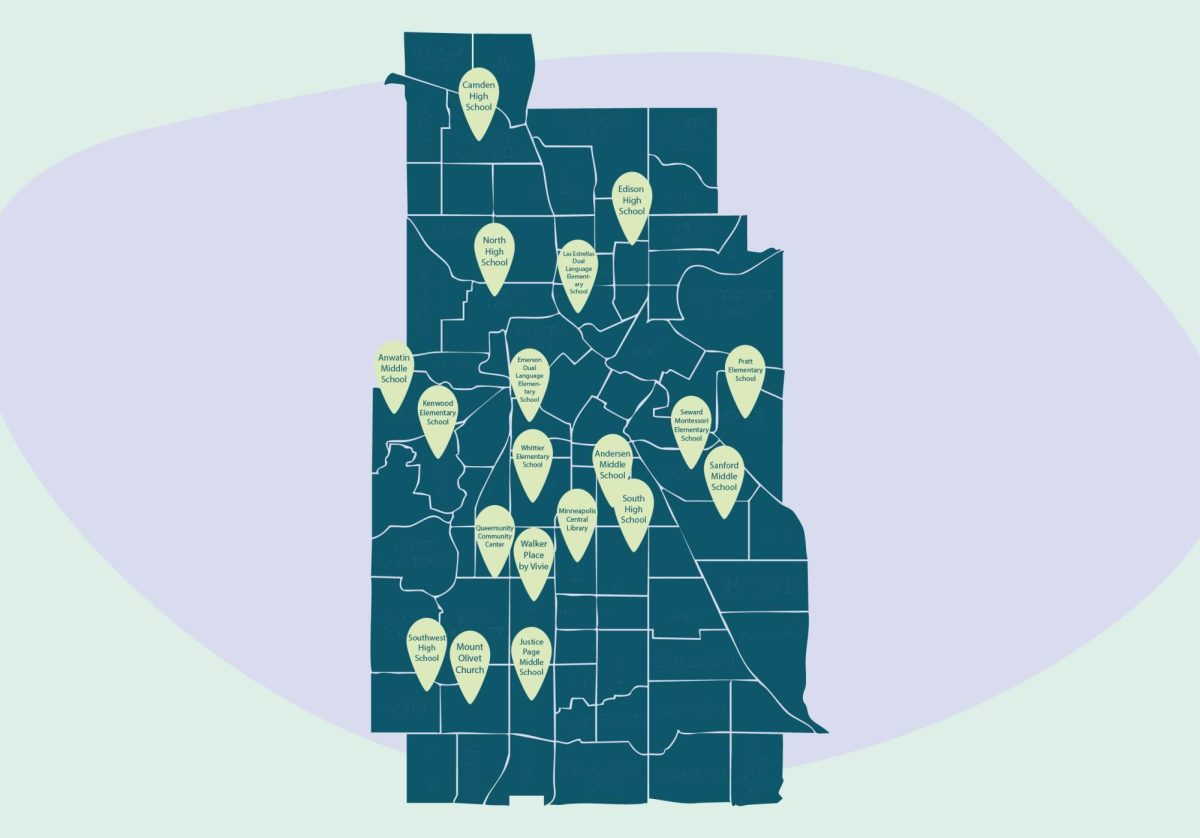

Starr said painting a mural on a bare wall typically dissuades people from defacing it, as some nearby buildings have done. She said WBBA used the Minneapolis Facade Improvement grant to fund art in Cedar-Riverside following the vandalism in 2020, and this grant could be used to help the mosques.

However, Bihi said if vandals targeted the mosques purposefully, putting art on the wall might only draw unwanted attention. There are not currently any signs that identify the building as a mosque, and the presence of Islamic art could eliminate the mosque’s anonymity to people who do not live in the neighborhood.

For businesses, the University of Minnesota provides money through the Good Neighbor Fund that Starr calls “security art.” House of Balls artist Allen Christian said he will paint art on large aluminum sheets that cover and protect business windows as security screens.

“It’s about creating a safe space for these businesses, using material that does that but also allows light in, allows a sense of playfulness and allows the uniqueness of the business to come through,” Christian said.

Christian said he plans to focus on the project this winter, and his first client will be the Mediterranean Deli on Cedar Avenue. He said he expects each interested business’ screens to take about one month to create.

“If something bad happens to this community, it doesn’t really divide us, it actually brings us together,” Bihi said. “No matter what people do or say to threaten this community, we have neighbors who will have our back, and that’s something priceless.”

Richard Turnbull

Oct 20, 2021 at 7:19 am

Fortunately the human sense of justice and fairness is more powerful than hate.

Allied with art, which rightfully frightens the morally dead, soulless people who vandalize to terrorize people, it’s even more powerful.

Be sure to look for Mr. Allen Christian’s works around here, for example at Art-a-Whirl in Northeast Minneapolis every May, you will not be disappointed!