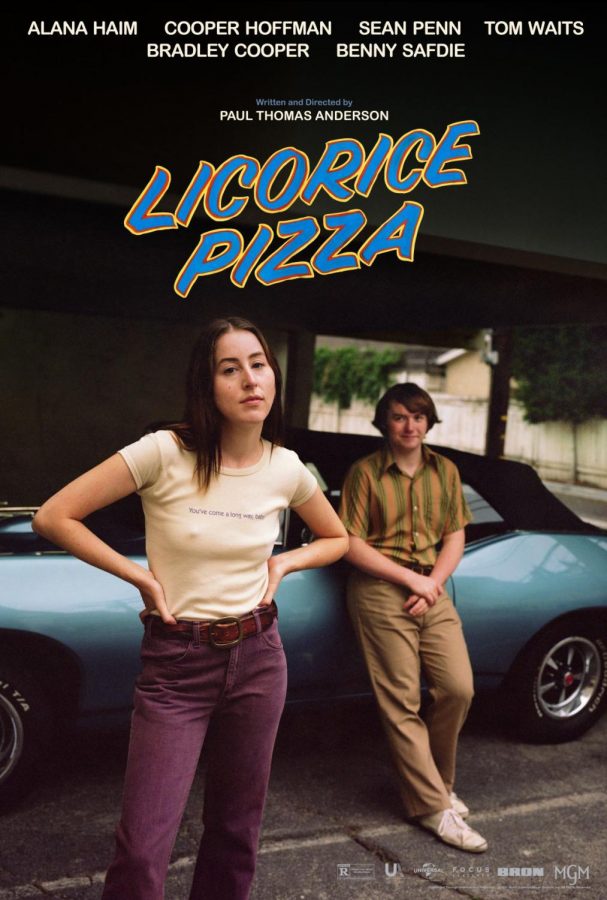

“Licorice Pizza” is director Paul Thomas Anderson’s ninth film and the first to fit neatly within the ever-popular coming-of-age genre.

Set in California’s San Fernando Valley in 1973, the film is loosely based on the memories of Gary Goetzman, a former child actor and co-founder of Tom Hanks’ production company. Newcomers Alana Haim and Cooper Hoffman shine in breakout roles as Alana Kane and Gary Valentine, an unlikely pairing (boasting a 10-year age gap) that find themselves entangled in a complicated relationship characterized by their joint antics and the push and pull of adolescence and adulthood.

“Licorice Pizza” find its niche through its venture into the wild world of waterbeds, the outlandish realities of navigating Los Angeles in the ‘70s and a hang-up in the midst of the period’s gas shortages featuring a sleazy Bradley Cooper, among other things, all while managing to center what it feels like to be both entirely certain and wildly confused about the possibilities of youth.

Here are edited excerpts from a college roundtable Q&A between Anderson and university A&E writers from across the country.

You have so many potential projects you could pursue — why was this the one you wanted to direct and take to the finish line?

It really is just surrendering yourself to what’s inevitable and in front of you and a feeling of unquenchable thirst for something. You think, “there’s no way I’m not doing this.” Even if we can only get five dollars, we’re still making this movie. Once you have that feeling — you know you’re powerless and the film is what your life is going to be.

Is there something special about being the director behind two debut performances for your lead actors?

There’s something really exciting about it. I know what it’s like as an audience member and you see somebody on the screen that you’ve never seen before. So, imagine that as the director of the movie. I kind of have built this movie on the premise that the actors could do it, and they did it. It gives you proud papa feelings.

Both leads sort of toe this fine line between adolescence and adulthood, seeming at once childlike and at other times sternly responsible. What’s it like to display the complexities of navigating a platonic romantic relationship on screen?

What’s interesting about their relationship is that what it appears to be initially is not what it is. He appears to be this irritating, smooth-talking kid who has all these hare-brained schemes; she seems to be a fully grown, intelligent, strong, young adult woman. Within five to 10 minutes you realize he’s completely stable, responsible for raising his younger brother, he’s a good businessman and he’s emotionally mature. And what you realize is even though she’s older, she’s very unpredictable, emotionally immature and stuck firmly in her adolescence. She’s not anxious to grow up (even though she might say she is); she’s doing everything she can to stay young. This is an interesting dynamic and actually creates a lot of dramatic and comedic possibilities. The idea that two people can’t be together instantly creates a dilemma. This is a very traditional formula for 1930s romantic comedies, which really stand the test of time to me.

When you’re filming a scene, do you know at that moment what song is going to be playing or is the movie’s soundtrack something that you figure out in post production?

It’s a combination, but I would say that the majority of it is figured out beforehand in the writing process. For the major sequences, the David Bowie song playing was always planned to be there, the Paul McCartney song was always planned to be there, Nina Simone singing “July Tree” was always planned to be there. Now, that leaves open many more possibilities for discovery in the editing room.

What was it like releasing a film in the pandemic and what do you hope for the future of filmmaking post-pandemic whether in films you might make or the process of returning to movie theaters?

The great thing about releasing a film right now is that movie studios are looking at what it means to make a film and release it and they’ve thrown their hands up and said, “We have no idea what to do.” Now in the land of unintended consequences here, that’s very exciting. That means that there is room to do things differently and in a new way. So we’re trying a lot of actually not revolutionary but very old fashioned techniques to get the movie out there. What seemed to happen recently with films is they would just kind of get carpet bombed into existence and then forgotten about within two days. So we were trying to sort of raise people’s awareness over a long period of time instead. We’re so used to consuming things so rapidly that to stop and to give audiences a chance to breathe, or at least present the film in a more respectable way, in turn gives respect to an audience.

You used equipment and processes from the 1970s — did this pose any technical challenges in regards to the filming?

There’s an old light called an arc light — literally a carbon arc. Using it was like resurrecting an old ‘57 Chevy Bel Air that had been sitting in a garage for 30 to 40 years that had never been turned on again and trying to fire it up and having it run the Indy 500.

It gives you a quality of light that is absolutely incredible. Finding the carbon arcs was hard, finding people who knew how to work the lights was very hard. They’re very large, they’re very impractical. That was something that was technically challenging but absolutely worth it once you finally got these lights turned on. It was one of those magical things where you realize through the labor of it why no one does it anymore.

What’s something that you’ve taken away from the filming of “Licorice Pizza” and what’s something that you hope viewers will take away from watching the film?

When I started working with [Alana] Haim and we never had any money, we never had any time and we just did what we could with what we had. We had a similar situation with this film. We had to shoot it quickly, we had to shoot without too much thinking about it — just instinctual. We were really using all of our friends and all of our family to make the film. So if anything, it verified this belief that you really don’t need much more than the desire and a handful of friends and family to make a great film.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.