A recent University of Minnesota study raises concern and advocates for increased food security on a national scale within food assistance programs’ distribution rollouts.

Stemming from a Project Eat cohort, postdoctoral associate Vivienne Hazzard analyzed 75 Minnesotans who experienced food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study is aiming to explore if their food insecurity was due to unpredictable and unpatterned food consumption on a daily basis.

Seventy-two percent of the sample demographics were Black, Indigenous and people of color.

“We definitely see that food insecurity disproportionately affects marginalized groups in terms of race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation and socio-economic disadvantages,” Hazzard said.

The study modernizes traditional surveys by sending text messages to subjects five times a day for a two week period. Questions range from if they skipped meals or reduced the meal size due to economic insecurity, to what mental and physical symptoms they felt after binging.

Some participants engaged in what Hazzard described as a “trade-off-strategy” as a last resort, which is commonly used as a coping skill when food is extremely scarce. The scale included “skipping paying bills to buy food, asking friends or family for food (or money for food), to borrow to make it through the rest of the month,” Hazzard said.

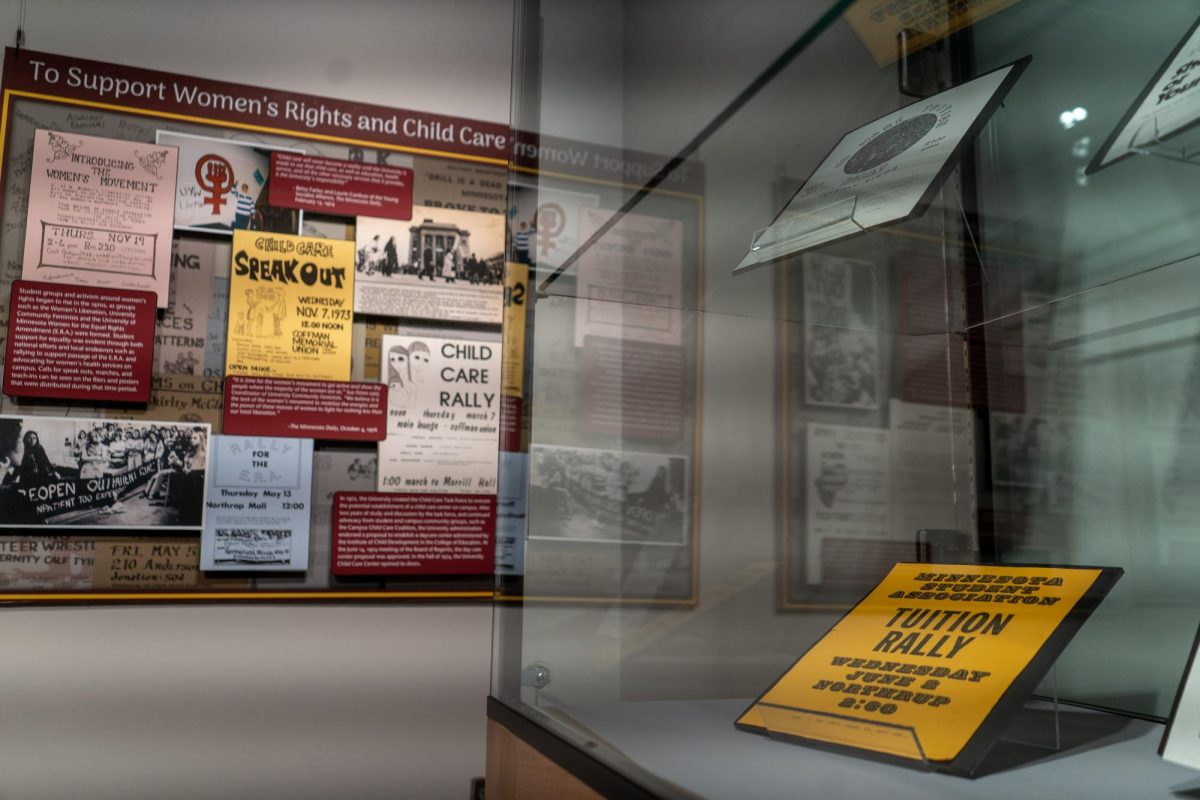

Within the study’s first table of sample characteristics, 47% of participants reported using food assistance programs over the last month. Furthermore, 41% of participants reported the usage of charitable food assistance programs over the past month. Some of the most common food assistance programs used were the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

One of the primary motivations for conducting this study was Hazzard’s evidence beyond the study, suggesting behaviors people develop during periods of food insecurity may endure beyond these periods, even when food insecurity isn’t present in the household.

Anna Bishop, a registered dietician nutritionist who works with the Center for Collaborative Health MN, also highlighted the inequities those who experience food insecurity face in healing their relationship with food.

“I would categorize food insecurity as trauma,” Bishop said. “Like other forms of trauma that have life-long effects, the restrict/binge cycle often continues even when someone is no longer experiencing food insecurity.”

According to the National Eating Disorders Association, intuitive eating is the practice of instilling trust within your body’s unique needs to make choices around food that feel good for your body’s unique needs.

Bishop said this concept may look different within individuals experiencing food insecurity compared to other situations due to the lack of trust in food availability.

Part of Bishop’s approach is using a non-diet approach for clients to find balance and peace with not only their body, but also with food.

“Working with individuals experiencing food insecurity takes a different level of creativity. We work to create meals that meet their needs using the foods that are available to them,” Bishop said. “This often means having a limited variety and working to make foods last longer.”

The concepts of guilt and shame while at the grocery store within binge eating may also look different for those experiencing food insecurity. Bishop said she recognizes beyond just providing food to those in need, there should be food available that attributes to one’s cultural framework and practices.

“To create an environment that promotes food as something that should be intuitively enjoyed would mean making sure low-income people have access to enough food and enough variety to meet their nutritional needs. Not just once a month, but everyday,” Bishop said.