Think about the last time you went to the DMV. You know you’re eligible for an ID or driver’s license, but you may have put it off because let’s be honest — it’s a hassle. Even though you’re eligible, you still have to prove you’re eligible by bringing relevant documents, standing in line, filling out forms and so on. This is similar to what public policy scholars refer to as “administrative burden.”

Administrative burden is “the costs that people encounter when they experience policy implementation,” said Don Moynihan, a Georgetown public policy professor who co-wrote a seminal book on the topic with Pamela Herd.

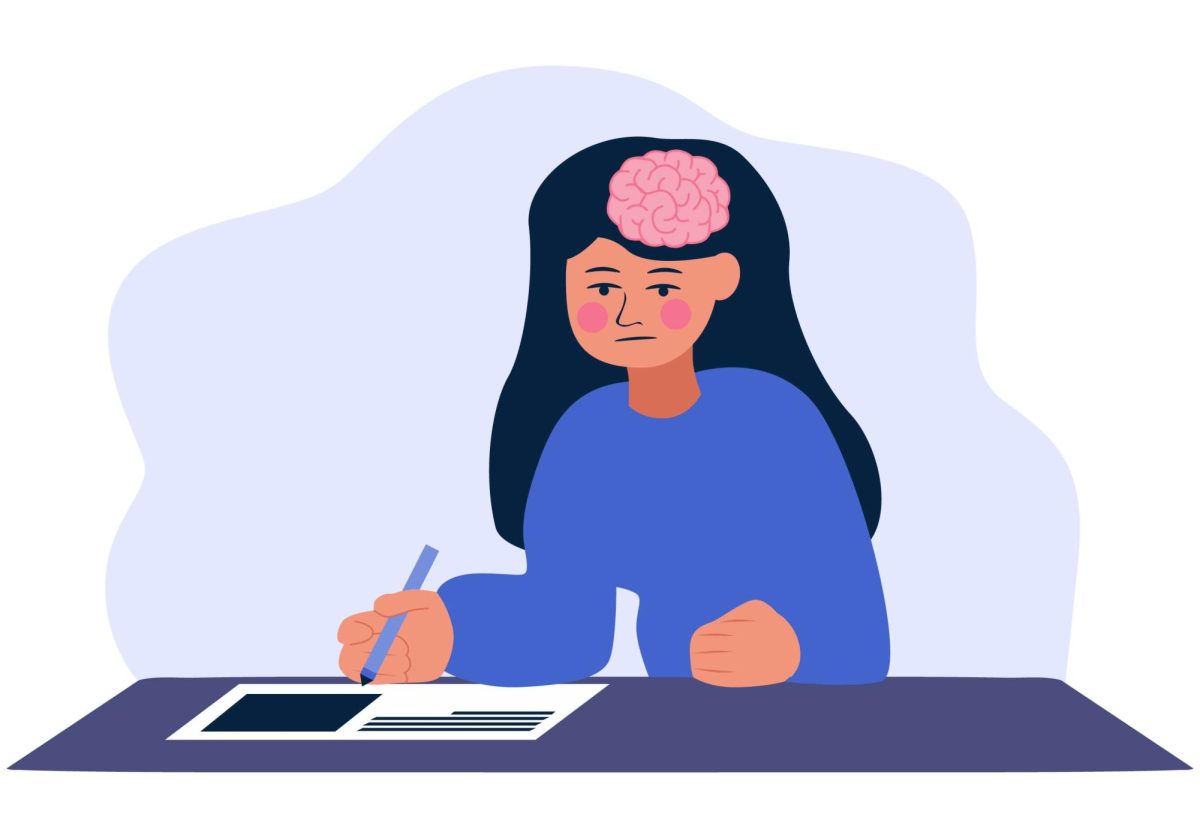

There are three main types of costs associated with administrative burden. First, people have to learn that programs exist and figure out if they’re eligible — these are learning costs. Second, people may encounter psychological costs such as the stress of navigating bureaucracy and the stigma associated with some programs. Third, compliance costs are the burdens associated with filling out forms, collecting documentation, waiting to speak with someone and so on.

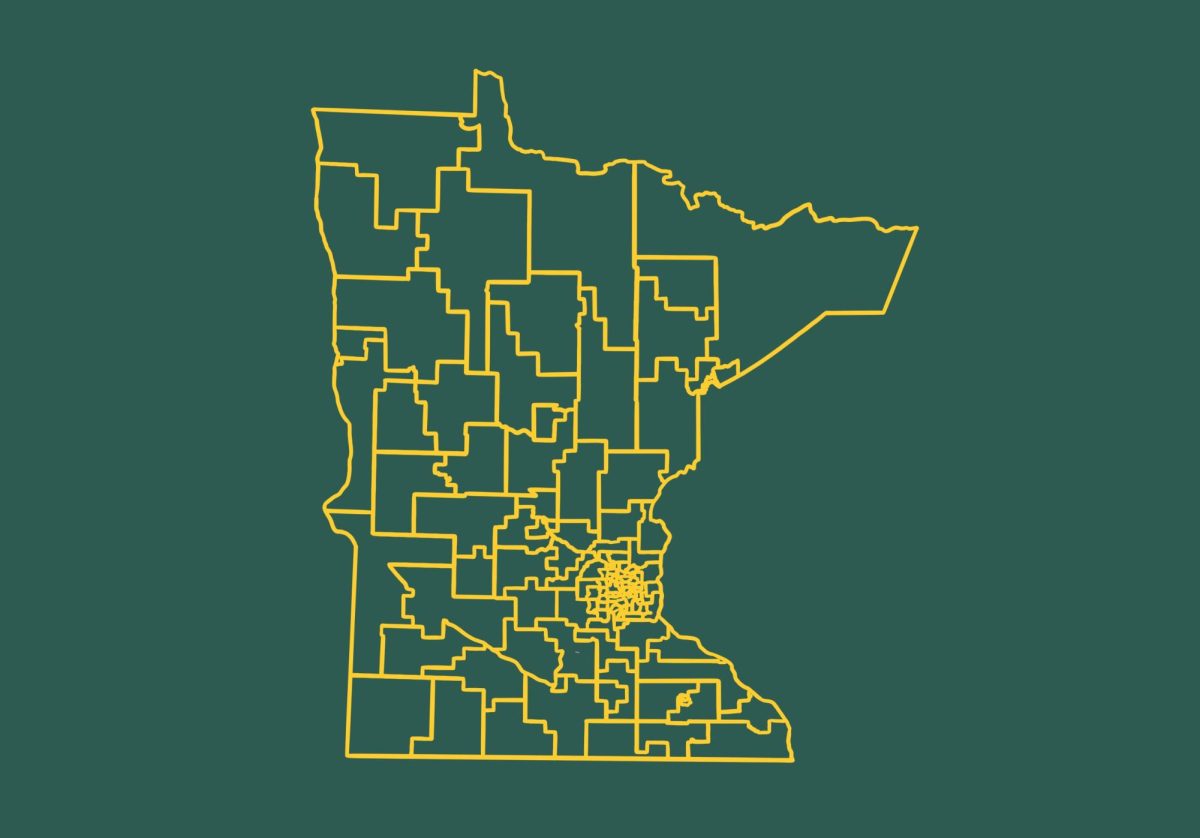

Moynihan said many of our most contentious political debates, like those over voting and abortion, have to do with administrative burden. “A lot of the debates we have on voting center on how easy or hard it should be, so how burdensome it should be,” he said.

An important policy area where people encounter a lot of administrative burden is programs that seek to alleviate poverty and provide health care, like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or Medicaid.

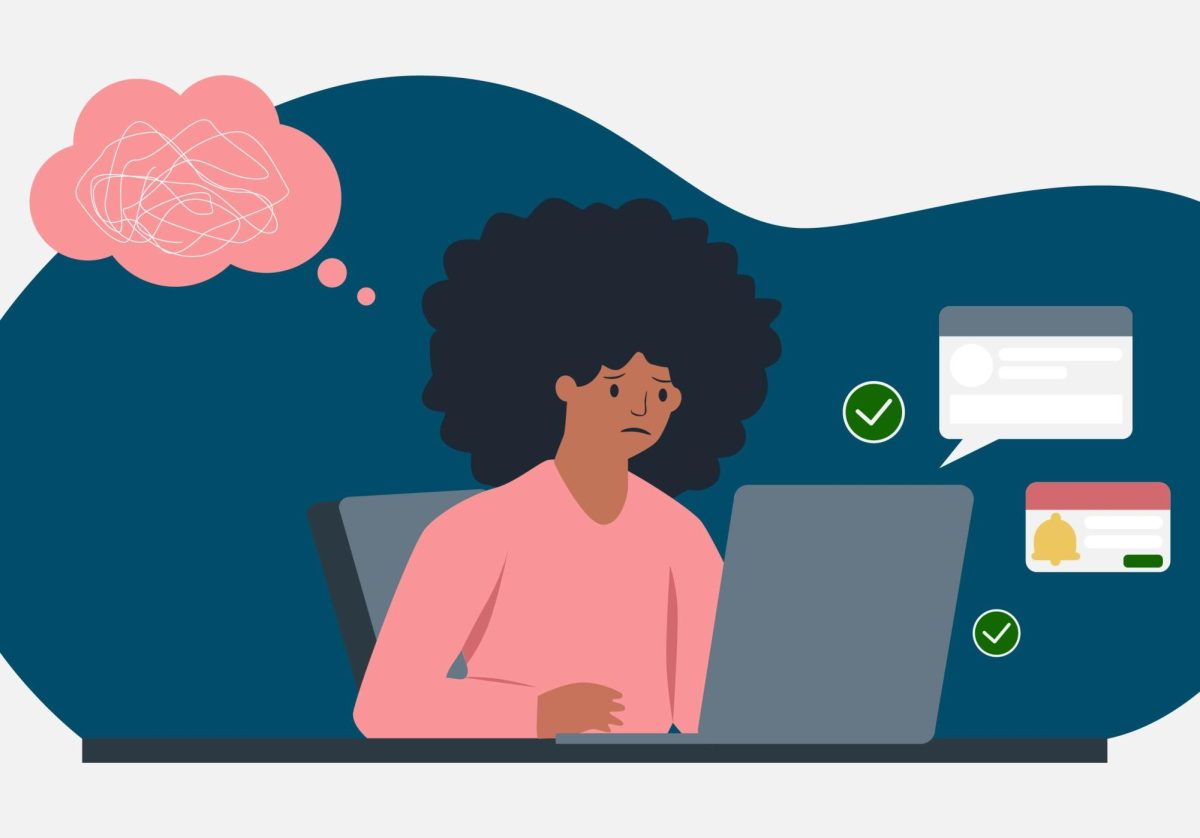

“Once you start to get into the reasons why people aren’t able to access these benefits, oftentimes, it’s not because they’re ineligible. It’s because they can’t find the information they need; they’re not sure if they’re eligible and they’re afraid of some sort of negative consequence if they apply and are rejected,” said Juliana Zhou, a policy analyst at the Center for Law and Social Policy, a liberal research and advocacy group. “That’s often the case with immigrant communities, so they just won’t chance it.”

Iris Arbogast is a researcher who co-wrote a recent study that looked at why children’s enrollment in public health insurance declined from 2016–19. She and her co-authors found administrative burden played a role in this decline.

“If you can imagine it being difficult to fill out taxes if you’re a college-educated student, imagine doing something more difficult than this to get health care if you barely speak English, or you didn’t go to high school. It’s very confusing and stressful,” Arbogast said.

One example of a policy change that increased administrative burden is when Mississippi started requiring Medicaid recipients to report every change in income of $100 or more.

Previously, they only had to report if their income went above 130% of the poverty line.

And Missouri implemented an auto-checking process that sent some people a letter in the mail stating they had 10 days to respond or they would lose coverage. A survey of 37 Missouri health care providers found 87% of the people who lost coverage still met income requirements, but they had trouble with the renewal process.

Administrative burden hits immigrants and people of color particularly hard, according to experts.

“A lot of Hispanic families or Asian families are mixed-status families, and the vast majority of children in immigrant families are U.S. citizens, but they do not have access or they are not even eligible for benefits,” said Yiyu Chen, a research scientist at Child Trends.

Chen brought up the example of the Earned Income Tax Credit, a powerful poverty-fighting program.

“In order to qualify for the EITC, everyone on the tax return must have a work-authorizing Social Security number,” Chen said. This means even if their children are U.S. citizens and they pay taxes on their income, undocumented parents cannot apply for the EITC.

But these eligibility requirements aren’t the same for all programs. According to Chen, undocumented parents of citizen children are allowed to apply for SNAP on their children’s behalf.

“If you look across programs, if you look at TANF, SNAP and EITC, you will see that the eligibility restrictions are very different,” she said.

This creates a lot of confusion for immigrant families. Since different programs have different immigration status requirements, it might be too confusing, or parents will mistakenly think they can’t apply for any benefits for their children.

There are some ways to reduce administrative burden.

“You can simplify processes, or you can invest more in capacity and probably do a little bit of both,” Moynihan said.

He gave the example of Social Security as a program that has complicated requirements but has shifted the burden onto the government.

“We built an infrastructure to make it feel simple for people,” he said. For instance, many people don’t have to track their income across their careers because the government and their employers do that for them.

Soon, we may see an increase in administrative burden due to the end of the COVID-19 federal public health emergency. Multiple experts said this period has seen some temporary changes that reduced administrative burden. “There’s a lot of innovation,” Chen said. “In SNAP, there was extended certification periods.”

Arbogast said during the emergency period, states weren’t allowed to kick people off of certain programs. But now, they’re going to be sending lots of people letters asking to verify their eligibility, which may pose a problem as it’s been a long time and people may have moved. Administrative burden “hasn’t been a problem for the last couple of years, and it’s likely to come back in full force,” she said.

“Administrative burdens aren’t just a set of policies,” Zhou said. “I would define them more as examples of this overarching mindset of suspicion with which our public benefits programs treat enrollees or applicants.”

Some ways of reducing this suspicion, she said, would be to give people more time to appeal rejection decisions or automatically enroll them in other programs they’re eligible for once they’re in one program.

“That basically makes it possible for people to have access to all of the benefits for which they are entitled, and not asking them to go through nine different processes with, like, three different agencies in order to access the support that they need to live,” Zhou said.