Layal Almosa just had a baby.

“He’s the cutest,” she laughed. “Yeah, he stays up, but he’s so cute.”

Almosa is pursuing a master’s in English at the University of Minnesota. As a graduate worker with a 50% assistantship appointment, she was able to take six weeks of paid family leave, which she is about halfway through. But she’s not sure that’s enough.

“I think before I had the baby, I thought that [six weeks] was, like, amazing,” Almosa said. “And now, being in it, six weeks is super fast.”

This week, Minnesota legislative committees considered a bill to establish guaranteed paid family and medical leave for all workers in the state that was introduced to the Legislature in January. The policy would operate as a social insurance program similar to the state’s unemployment benefits program. It would offer Minnesotans up to 12 weeks of paid family leave and up to an additional 12 weeks of paid medical leave per year.

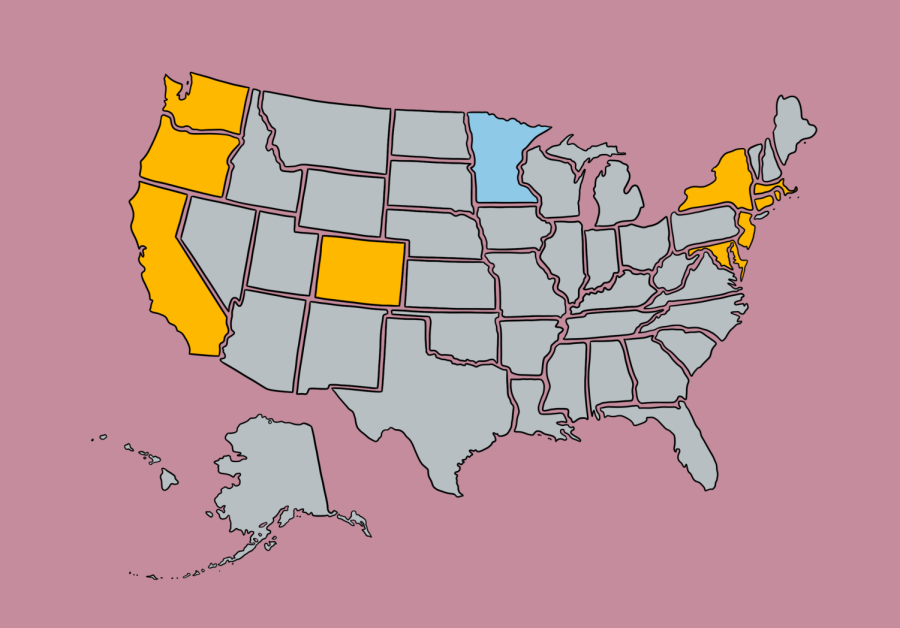

If passed, Minnesota would join 12 other states, including the District of Columbia, with paid family and medical leave programs. Currently, about 80% of workers in Minnesota, or 2.5 million people, do not have access to paid family leave through their jobs.

Critically, this bill would completely sever paid leave benefits from employment. The benefit would be portable, following workers from job to job, and would allow people working outside of a traditional workplace to opt into the program. This would particularly benefit self-employed workers, gig workers and even, potentially, graduate student workers.

David Wolfson is pursuing a doctorate in conservation sciences at the University and has two children. When the first was born during his master’s degree, also at the University, he wasn’t able to take any leave.

For the birth of his second child, while he was working, he had to save his sick and vacation days to be able to take time off. In 2018, before Wolfson returned for his doctorate, the University implemented the six-week paid family leave policy for those with 50% assistantships.

“I do feel like I could take time off if, say, I were to have a kid right now,” Wolfson said. “I think that’s not true for all grad students.”

If he couldn’t take paid leave through his University employment, Wolfson notes the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) would be his next resource if he needed to take time off to care for his parents’ medical needs, for example.

The FMLA is a federal policy that allows employees to take unpaid, job-protected leave for up to 12 weeks. It requires workers to have been employed at their jobs for 12 months and to have worked 1,250 hours in the year prior to taking their leave.

However, 62% of Minnesotans have no access to unpaid FMLA leave. And even those who do pay the price: in Minnesota, a typical worker who takes four weeks of unpaid leave loses out on almost $3,700 of income.

Graduate students face further challenges.

Although the 12 months of employment required by FMLA do not have to be consecutive, graduate assistantships are often contracted by semester or exclude the summer months. It’s possible for graduate students to be two years or more into their programs before they have been officially employed for 12 months and become eligible for FMLA coverage — and that’s only if they meet their 1,250-hour requirement.

That means graduate students, depending on their program and their funding situations, are not guaranteed access even to unpaid leave.

Almosa’s program doesn’t guarantee her a graduate assistantship, and she worries about securing a position for the fall semester. If there isn’t a position for her, she will have to pay full tuition and fees with no income for the semester and no benefits tied to her employment.

“That makes you want to think of taking a longer leave or a gap semester, or something like that,” she said.

This lack of guaranteed leave adds to the burden of inconsistent benefits and financial precarity that weighs on graduate students and bars many people from programs at the University.

“All those people who maybe can’t come or decide not to, it’s like an invisible absence, you know,” Wolfson said. “We’re not even aware of the enrichment that could come to our student body if anyone could feel like this was within their means. So that’s too bad.”

The University of Minnesota Graduate Labor Union – United Electrical, (GLU-UE) advocates for parental leave and clear paid time off policies in their platform online, a move that rightly calls out the urgent need among grad student workers for guaranteed leave.

But I argue the University is not the body that should be providing us, as graduate students, with paid leave. Any leave policy that is bound to our inconsistent employment will create gaps for people to fall into.

What about people who can’t work a 50% assistantship due to a disability? Or those working part- or full-time outside of the University to afford the often-astronomical cost of graduate school? What about those whose needs go beyond a six-week family leave policy?

The GLU-UE is right to prioritize paid leave for graduate workers, and an expansion of the University’s leave policy would benefit many. But, in the long run, we are better off supporting a state program. There is no upside to employment-related benefits if state-provided benefits are available, funded and well-administered.