A bill introduced into the Minnesota Legislature in February aims to combat mass teacher shortages by lowering the retirement age and reducing the consequences of early retirement to improve teacher retention; the bill is currently in committees.

For K-12 teachers, pensions serve as a retirement fund. The longer they work, the larger their pension is. In a career not often associated with large salaries, pensions give teachers a safety net to lean back on when their careers end.

Jehanne Beaton was a teacher for more than a decade and is the program coordinator for the DirecTrack to Teaching program, where aspiring students learn to become teachers. Beaton said Minnesota is struggling to fill crucial teaching positions because of dire underfunding of schools, salaries and pensions.

Spanish, math, science and career preparation courses, like woodworking and welding, urgently need more teachers, according to Beaton. Schools are also in desperate need of more assistants for special needs students.

What would change

For current Minnesota teachers, the retirement age is 66, the third-highest retirement age in the nation. If a teacher retires before then, their pensions are reduced.

While pensions are unlikely to encourage people to become teachers, Beaton said a better pension plan will keep current teachers in the field.

“The goal is to try and get people to stay in the profession longer,” Beaton said. “It’s a retention tool.”

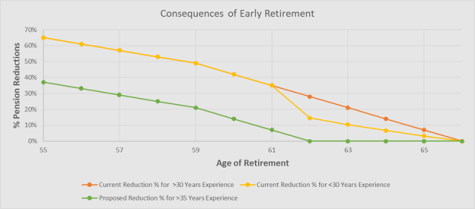

Under the proposed bill, a teacher can retire at 62 years old or with 35 years of service and receive full benefits. The bill lessens the pension reductions for early retirement.

To calculate teacher pensions, multiply years of experience by 1.9% and their peak 60-month salary.

Caption: Teachers could retire four years earlier and receive their full pension under the new system compared to the current system, if the bill is passed. Graphic by Jack O’Connor

Comparing the current and former pension systems using a teacher who worked 34 years, retired at 61 years old and made $70,000, currently, the teacher would receive $29,393 per year. However, if the bill passes, the teacher would receive about $42,055 per year.

Jack Lillestol, a senior at the University of Minnesota, is studying to become a middle school teacher. Lillestol said funding schools and financing teacher pensions leads to quality education.

“Everyone acknowledges education is important. Everyone wants their kid to receive a great education,” Lillestol said. “But not everyone is willing to recognize the finances that it takes to get that.”

Future of Minnesota teaching

Many future educators’ concerns go far beyond retirement pensions. Concerns include workload, college debt, workplace diversity, school shootings and political attacks against teachers, according to Beaton.

Beaton said current and retired teachers have been overworked and underpaid for years.

“Aspiring teachers go into schools and see how stressed and exhausted teachers are. They really question whether they want to do that work,” Beaton said.

Despite substituting and student teaching for less than one school year, Lillestol said he knows teachers leaving the profession, teachers who work summer jobs and that he has walked in on teachers crying.

While shadowing a current teacher, University student and aspiring elementary school teacher Alexis Wolt said her mentor warned her about the profession.

“I was shadowing a teacher I really liked,” Wolt said. “She looked at me and said ‘I don’t know if I can be a teacher anymore.’”

Teachers regularly work hours after the school day ends, have class sizes greater than 30, pay for teaching equipment out-of-pocket and lack the necessary funding to provide quality education, according to some Minnesota teaching unions.

Kyle Berg is a student at the University studying to become a high school history teacher. Berg said to solve the problems facing public education, Minnesota must increase school funding.

“Schools are just underfunded,” Berg said. “It’s a simple answer to a really long list of problems.”

Teachers say pensions won’t be enough

While not solving every problem, some teacher unions feel improving the pension system is a crucial step to take in retaining teachers.

“It’s not going to save everything, but it’s a good step,” Wolt said. “There is no one thing that the state can do or anyone can do to fix public education. If these steps keep being taken, we’ll get somewhere.”

Lillestol said far more needs to be done to fight the teacher shortage.

“It’s a very, very small step because it’s still asking teachers to go through an underpaid profession for many, many years,” Lillestol said.

Eliminating the teacher shortage requires promoting teacher retention and recruitment, according to Beaton.

While not unique to the teaching profession, college debt can be especially problematic for student teachers.

Student teachers must work at least 100 hours unpaid to finish their education and some must work a paid job if they can’t pay for tuition out-of-pocket, according to Lillestol.

“If you are going to Carlson, you’re getting a big return on school. That’s not really true with teaching,” Wolt said, referring to the University’s business school. “Paying off loans with a teacher’s salary is concerning.”

Regardless of the problems facing Minnesota’s future teachers, they still want to teach, according to Beaton.

“There’s still a lot of progress that has to be made,” Berg said. “But teaching is what I’ve always wanted to do.”