The University of Minnesota’s 5.8% decline in systemwide enrollment since 2019 is part of a nationwide downward trend in undergraduate enrollment at public universities and colleges, according to Vice Provost Robert McMaster.

At a Board of Regents meeting in June, McMaster gave a presentation on the University’s current enrollment situation, showing the 5.8% decrease in enrollment is closely aligned with national enrollment declines at public four-year colleges, which went down 5.9% from 2017 to 2020.

McMaster said a key factor causing the decline in Minnesota is the “alarming number” of high school graduates who are not attending any college after graduating post-pandemic, which he said has risen close to 38%. One reason for this is greater popularity among high school graduates of quickly securing a well-paying, full-time job.

“Students can go out and get pretty decent jobs right out of high school in terms of the trades or construction, and with pretty high salaries and good benefits,” McMaster said. “That’s very attractive for some students.”

McMaster added at the board meeting there is potential the University will face a “significant enrollment cliff,” as the number of high school graduates in Minnesota is expected to hit a peak at about 72,000 in 2025, before decreasing over the next decade to roughly 67,000 by 2036.

Declines in the number of high school graduates are also expected regionally and nationally, according to McMaster, with enrollment rates dropping about 5% from 2020 to 2030 in the Midwest, about 5.6% in the Northeast and about 2.8% in the West.

“There just simply will not be enough students coming out of United States high schools to support the entire infrastructure of higher education moving forward,” McMaster said.

McMaster added the trend is caused by declining birth rates among some populations in the state, with Minnesota’s growth coming mostly from increased migration of international citizens.

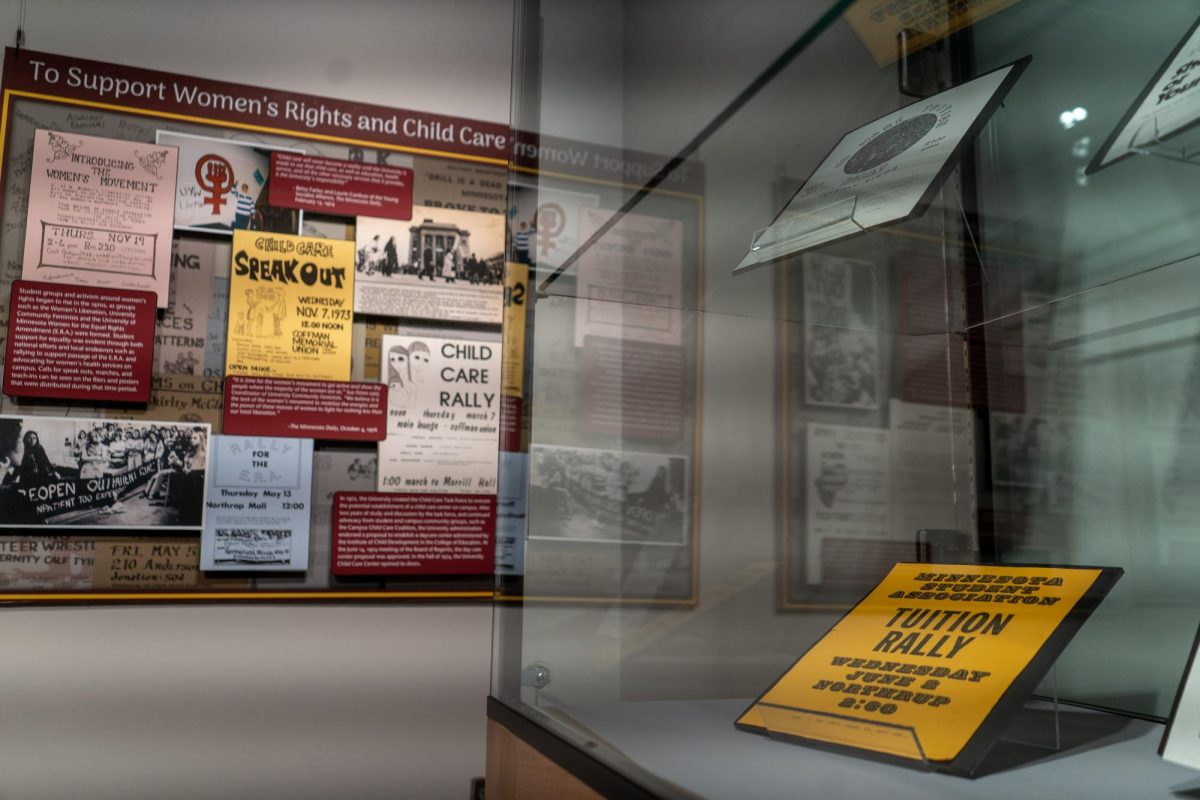

As part of its MPact 2025 goals, the University hopes to increase its percentage of Minnesota high school graduates who attend one of the University’s campuses to 12%. Since 2000, the number of high school graduates from the state attending the University has hovered around 10%. The University has not hit 12% in that time.

Despite the projected decline, McMaster said this does not affect the 12% goal and he believes it is achievable over the next few years because of the increase in options students have to afford college.

“We have a number of new financial aid programs that are in place: the promise plus, the Native American promise program, the Benson scholarship match, there’s a series of these scholarship programs,” McMaster said. “We’re pretty confident that we’re going to be able to get at and maintain that 12% in the next few years.”

McMaster said the University works in the Big Ten Academic Alliance, where the vice provosts and deans for undergraduate education of Big Ten schools meet at least twice a year to discuss enrollment trends and scholarship opportunities.

“We all know we’re competing for the same students and we kind of put that aside and try to prioritize what’s good for the Big Ten, and how to improve student success among all of our campuses,” McMaster said.

Regional UMN campuses face steeper declines

Within the University’s overall 5.8% decrease in systemwide enrollment since 2019, the Greater Minnesota campuses have been significantly more affected, according to McMaster.

Since 2019, enrollment at the Twin Cities campus has dropped 2.6%, while enrollment at the Greater Minnesota campuses has gone down a combined 13.9%, according to McMaster’s presentation.

Both McMaster and the interim vice chancellor for enrollment management at the Morris campus, Melissa Bert, said a big reason for this is a nationwide increase in popularity and attractiveness of national flagship campuses, like the Twin Cities, which has correlated with a decrease in the popularity of smaller and regional campuses.

“There are so many different pieces of evidence that indicate that flagship institutions are, especially post pandemic, just doing better than non-flagship campuses. There are a variety of reasons for that, but they have more significant name recognition,” Bert said. “It’s really a national phenomenon that has happened before and is kind of the nature of higher education.”

Bert added challenges the Morris campus is facing include not being able to do the same level of in-person recruitment during the COVID-19 pandemic and lower retention rates of students who start college at the Morris campus.

Sue Erickson, the interim director of enrollment management at the Crookston campus, said a trend affecting their enrollment is fewer males applying to the school. Erickson added Crookston had a majority of male students on their campus until 2019, and now have about 60% females.

“There’s a declining level of confidence, particularly in rural parts of the state, on the value of higher education, and where it’s really hitting is in rural males, who have historically gone on to higher education,” Erickson said.

Other rural areas across the country are seeing a similar trend, and part of it is because of the high-paying jobs in the trades people can get after high school, jobs that often attract more men, according to Erickson.

Erickson added this development has caused questions on what can be done to make higher education a more appealing option for males.

“When I first came into higher education, we looked at what types of students we were providing for, various demographic groups, and the white male student was always looked at as the ‘privileged’ or ‘advantaged’ class,” Erickson said. “Now there really is some rumblings of ‘what do we do to support that group,’ because eventually if trends continue, there will be a gap of educated young men in the country.”

Both Bert and Erickson said their respective campuses have increased their marketing and recruitment efforts, and both believe the enrollment numbers will “stabilize,” having a chance to grow over the next decade. The Morris and Crookston campuses often collaborate in their recruitment process, according to Bert and Erickson.

Erickson said Crookston plans to grow their enrollment by investing in their online programs, giving students a wider range of options for classes. Bert said Morris particularly struggled during the COVID-19 pandemic because they lost the in-person and tight community feel of the campus that was crucial to its appeal.

“It really is a community, and when you alter that community, it is a challenge to try and not necessarily get back to where we were, but to get back to a new version of who we are,” Bert said. “We are definitely back to some of who we are.”

Jeff Ertelt

Mar 10, 2024 at 3:25 pm

I have one comments, Minnesota Higher Education is way to expensive. Go to North Dakota, Valley City, Mayville, Dickinson. Way cheaper and Way less DEI burden.

Jason

Nov 30, 2023 at 12:51 am

This article is talking about similar information that the MN state schools are going through now. Saint Cloud state is experiencing severe enrollment declines and they are having to make severe budget cuts to make ends meet. The solution? Cutting programs to fund the programs that give a university its identity. Mankato is reducing its over 140 programs and focusing more on its aviation program, because it’s the only in-state school to offer aviation. I suspect a lot of other institutions will follow suit in the coming years.