Kristin Henning lectured at the University of Minnesota Law School Nov. 28 to talk about criminalizing normal adolescent behaviors and youth justice.

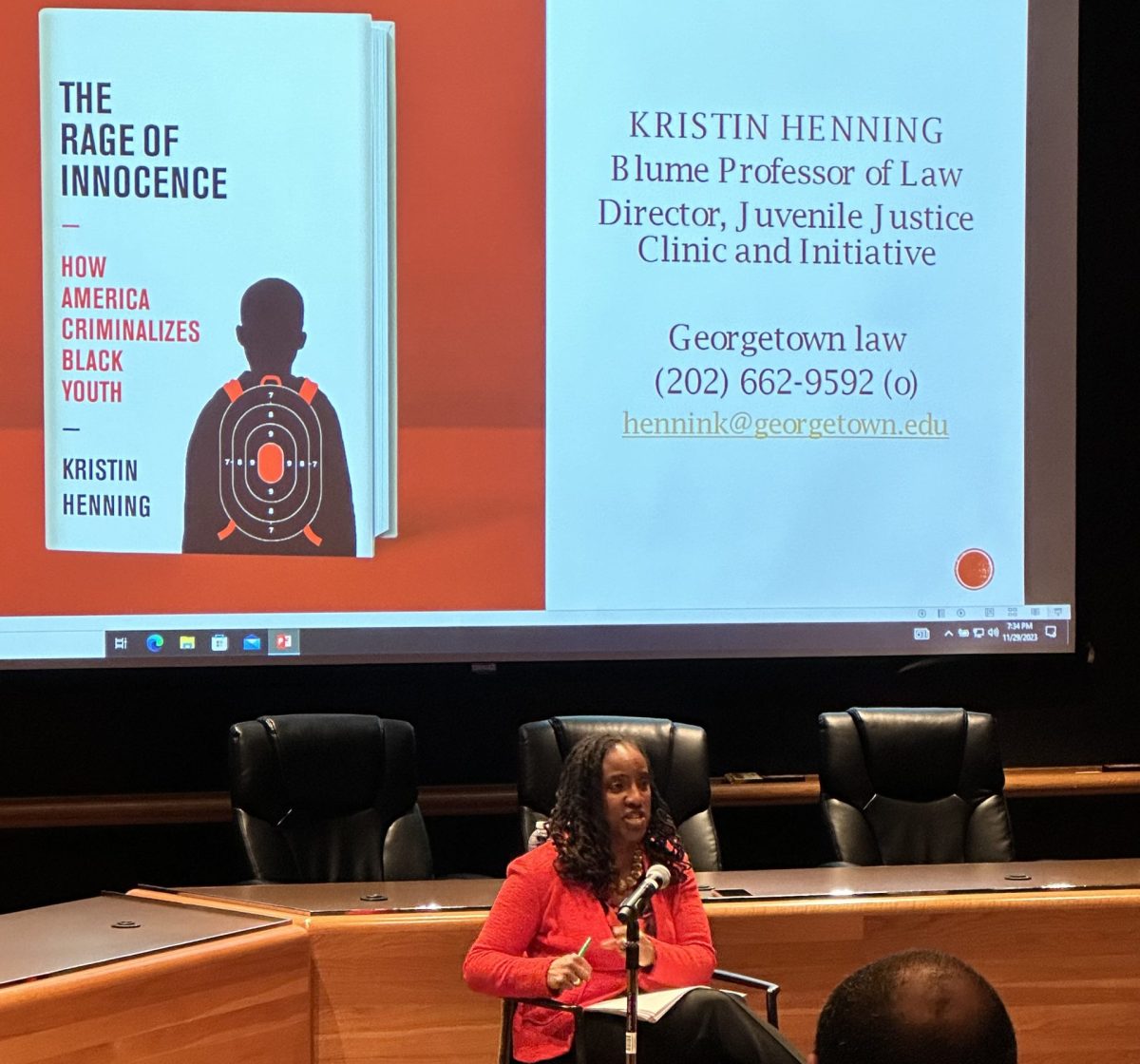

Author, Blume Professor of Law and Director of the Juvenile Justice Clinic and Initiative at Georgetown Law, Henning discussed topics related to her book, “The Rage of Innocence: How America Criminalizes Black Youth,” at the University’s Law School.

Henning said she decided to write the book, which is a collection of stories about children she has represented, to help people understand what children, especially children of color, were experiencing.

For 26 years, Henning has represented children in Washington D.C., where she lives. During the lecture, she said she has only represented four white children in her entire career.

“You would think that white children never commit a crime, never engage in the same kind of impulsive, delinquent behavior that all kids all over the world do because you never see that in court,” Henning said.

Henning has given similar lectures to prosecutors, probation officers, judges and lawmakers at law schools, universities and courthouses. She said her goal is to help these people understand how children of color are deprived of an opportunity to be children like every other child across the world.

A part of what Henning does when she lectures is provide examples of how children can be impulsive and take risks, pushing boundaries like many teenagers tend to do. She said it is the nature of teenagers to experiment with drugs, sex and alcohol.

“By and large, we allow children, white children and wealthy children to make mistakes, learn from their mistakes and move on to prosperous and thriving lives,” Henning said. “When Black, and sometimes other brown children make mistakes, we’re quick to arrest them, detain them in juvenile facilities and give them a criminal record that prevents them from getting a job or having opportunities.”

Another topic Henning discussed in her lecture was discipline, even for children who engage in disruptive adolescent behaviors. Discipline can be done in ways that are restorative and trauma-informed, Henning said.

Henning also talked about police presence in schools.

“Most people don’t realize that there is empirical research documenting how psychologically traumatic that police presence can be in a school and how police presence can undermine the school climate and make it hard for students to learn,” Henning said.

From the university perspective, Henning said the psychological impact on college and university-level students of color is the same. There is research demonstrating these police environments, particularly for Black and brown people in contemporary America, are psychologically harmful, according to Henning.

“Police-free schools … is really not as radical as people want it to be, and should not be as controversial as people want it to be because there are clear alternatives,” Henning said.

According to Henning, some of these alternatives to ensure safer schools without using police include smaller class sizes, social-emotional learning courses in the curriculum and the continuance of mental health services.

While Henning said she knows universities are worried about mass shootings, “research shows that police presence doesn’t actually prevent those kinds of disasters.”

Henning encouraged attendees to have eyes open to the big picture and become advocates. She said one way to heal young people is to create space for young people to talk about these issues, even if that means a space where young people can curse or be angry.

Bear Morgan, a fourth-year political science student who attended the lecture, said it is important to create these opportunities for young people even though it is hard on a university campus.

Morgan said Henning’s lecture and topics are important to him because he was formerly incarcerated as a juvenile.

At the age of nine, Morgan said he was charged with a misdemeanor and subsequently got into a bad crowd, where he became gang-affiliated at the age of 14.

“Kids are impressionable, right, it’s pretty common,” Morgan said. “For me, I got pulled with the wrong crowd, so I started doing dumb stuff.”

Now, Morgan works as an advocate for youth, participating with advocacy groups like Face to Face and Proof Alliance.

“The discussion doesn’t necessarily have to be about being a professional, but more so how do we create an inclusive environment for people who come from backgrounds that are underrepresented or marginalized to have a space here,” Morgan said.

Lauren Hamilton is a law student at the university and serves as the president of the Women of Color Collective and vice-president of the Black Law Student Association. She said while she believes there needs to be a massive reform and restructuring systematically, students are working on creating those safe spaces with school support.

“We’re trying to build and make more space, especially for women of color in this area to have room, have a voice,” Hamilton said.

Shannon Kuster, a graduate student at the law school and president of the Criminal Justice League, said these things have not historically existed, and law schools are so “historically white and wealthy” that the open and honest spaces that Henning mentioned are not built in.

Kuster said the allowance of these spaces is a recent development and the improvement of bringing different voices into the law school has made a difference in the amount of students who advocate for those kinds of spaces.

“A big part of the problem is that people don’t understand a) the differences between youth and adults in this context and b) since all this is closed to the public, people don’t actually know what happens in the juvenile system,” Kuster said.

Hamilton said this is not necessarily just a legal issue, but it extends to multiple facets, meaning people outside the law school also have a connection to this in some way.

Michael Harrell is a second-year student who also attended Henning’s lecture. While he said he knew a lot of what Henning talked about, it was alarming to see the statistics.

“If you don’t experience these things, I think just being in the conversation, even if you don’t have anything to say, just being there experiencing it for yourself, you will pick up something new and you will learn about your neighbor,” Harrell said.

According to Harrell, there are some spaces on campus for Black students, but the University could push for more safe spaces for minorities or people who come from marginalized backgrounds.

“Being a student here, I feel like there are some spaces, like the Black Student Union, but I don’t feel like there’s enough spaces compared to our white counterparts,” Harrell said.

Henning said the takeaway message is to not embarrass or shame children or put them in jail if they make mistakes. It is more important to help them, redirect them and support them.

“Black and brown children are children too, and we have to let them be children,” Henning said.

This article has been updated.

Thomas

Dec 7, 2023 at 12:01 pm

The delusion here is frankly unbelievable.