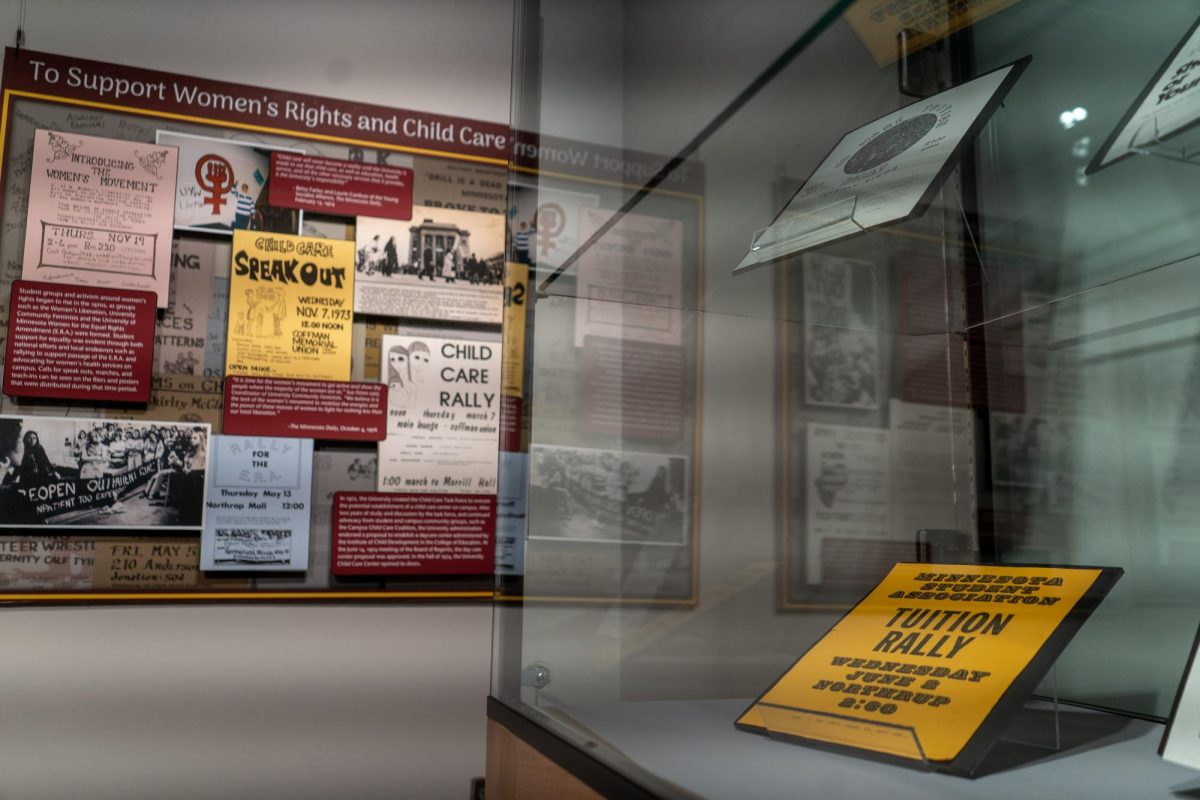

Each year, the University of Minnesota markets its clean, well-kept campus to prospective students as a selling point.

Michelle Garvey, a University professor, sees it as something else: exploitation.

Garvey, who has taught an environmental justice course since 2017, has been taking her students on “toxic tours” to explore environmental inequities in the Twin Cities, she said.

These tours show how resources are diverted away from communities of color to white spaces, Garvey added. Exploited communities disproportionately experience poor health outcomes, income inequality, a lack of fair housing and pollution.

“I unfortunately have been very frustrated with the University of Minnesota’s lack of commitment to environmental and climate justice,” Garvey said.

The University announced a new center in April headquartered at the University of Minnesota to address environmental justice in the Midwest.

The Great Lakes Environmental Justice Thriving Communities Technical Assistance Center (TCTAC, commonly pronounced tic-tac), is one of 17 centers in the U.S. funded by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which will provide grant assistance to support clean energy and environmental projects in historically disadvantaged communities, according to its website.

The center represents one of the initiatives by the University to further environmental justice through community engagement programs, projects and protests.

At an August roundtable discussion following the center’s opening, Nisha Botchwey, dean of the Humphrey School of Public Affairs, said environmental justice issues are not abstractions. They resonate deeply with University students, alumni, staff, faculty and beyond, she added.

“These are not just conversations,” Botchwey said. “They are steps towards a brighter, more equitable future.”

The EPA announced the 17 TCTACs, 14 regional and three national, in April. The centers are intended to remove boundaries in federal grant funding by providing training and assistance for communities undergoing the grant process, such as translation services, according to an April EPA press release.

The program is part of President Joe Biden’s Justice40 Initiative, which made it a goal to provide disadvantaged communities with at least 40% of the benefits of federal investments in climate change, clean energy and sustainability, according to the press release. These centers will help communities access funds made available through federal funding packages, including the Inflation Reduction Act and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

Defining environmental justice

Environmental justice is the equitable distribution of environmental harms and benefits, Garvey said. This approach analyzes why communities enjoy access to green spaces, bike trails, clean air, clean water and other benefits, while others do not, she added.

Uneven distribution patterns leave minority and low-income communities in areas with higher environmental degradation and far less access to green spaces, according to a University of Michigan Center for Sustainable Systems fact sheet.

In neighborhoods with a facility listed on the Toxic Release Inventory, which tracks where toxic chemical waste has been released into the surrounding environment, 56% of the population are people of color on average, compared to 30% in communities without such facilities.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also defines environmental justice as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people, regardless of race, color, national origin or income, to develop, implement and enforce environmental laws, regulations and policies,” according to a CDC fact sheet.

Other terms like climate justice have increasingly been used with environmental justice despite having separate foundations, Garvey said. While environmental justice has its roots in the American Civil Rights Movement, climate justice started as a global movement.

Today, climate change exacerbates environmental injustices with disproportionate effects on certain communities, she added.

In projections estimating an increase of two degrees Celsius in global average temperatures in the coming years, Black people are 34% more likely to live in areas with the highest projected increases in childhood asthma diagnoses, according to a 2021 EPA press release.

Those who identify as Hispanic or Latino also have a high participation rate in weather-exposed industries like agriculture and construction, according to the EPA. With two degrees Celsius of projected global warming, they are 43% more likely to live in areas with the highest projected labor-hour reductions due to extreme temperatures.

Energy justice and equitable access to clean energy is another component of both environmental and climate justice, Garvey said.

“I find that everyone defines and thinks of environmental justice differently, and that mosaic of thought can be really beautiful,” said Kate Nyquist, a communications manager for the University’s Institute on the Environment.

While Garvey agrees there are diverse approaches to these issues, she said not just anything goes. Garvey keeps her ear to the ground to listen to what frontline communities, or those that have been historically marginalized, are calling environmental justice.

Roles and goals of the new center

The new center focuses on providing underserved communities with technical assistance and access to the decision-making process, according to EPA project summaries.

The University will be working alongside Blacks in Green, another technical assistance center in EPA Region 5, to provide education, training, outreach, expertise and grant support to communities across the Midwest and 35 Native American tribes, according to the EPA.

Stephen Jeanetta, co-principal investigator for the Great Lakes center and associate dean for the University Extension, said the center plans to support those already working in the community.

In her remarks at the August roundtable discussion, Bonnie Keeler, principal investigator at the center and associate professor at the Humphrey School, said the center needs to disrupt the dynamic in which paperwork favors the powerful. This means creating new approaches, such as letting communities identify their priorities and leveraging the expertise of the center to break down any barriers.

The Great Lakes center will work with partner organizations throughout the region based on a hub and spoke model, Jeanetta said. The University of Minnesota will be the central hub, and organizations in each state will do some work on their own and connect back to the hub for resources.

“We think we can get a bigger bang by connecting everybody together and learning from each other and making sure that we’re simplifying how people access those resources,” Jeanetta said.

According to EPA project summaries, three activities are at the core of the new center:

- Identifying underserved and overburdened communities that could benefit from environmental and energy-related programs;

- Building capacity for communities to engage in environmental decision-making and access technical assistance;

- Providing tailored, accessible, culturally appropriate assistance that allows communities to secure funding and resources that materially improve their social, economic and environmental outcomes.

After an initially compressed timeline to put together a proposal, the center is close to launching, Jeanetta said. Now, those involved in the project are trying to determine how they can implement a work plan to support these communities.

They are trying to identify areas that meet their mandate to serve rural, remote and underserved communities, Jeanetta added.

Forms of assistance will vary depending on the community, according to Jeanetta. Some groups will need more access to engineering support or technical information, while others will need aid with organizational structure to help with program management or budgeting.

Part of this issue is determining how the center can help communities help themselves through sustained efforts over time, with one idea being to build networks between communities, Jeanetta said.

The University’s Department of Community Development, where the new center is headquartered, and the University of Minnesota Extension already have a strong network of organizations and programs working in communities, Jeanetta added.

The Great Lakes center is part of a larger network of 160 partners spanning the country, including community organizations, academic institutions and environmental finance centers, according to an EPA press release.

The center is funded for the next five years by the EPA, according to a University press release from Nov. 22. Keeler hopes to do long-term transformative work in that time.

“Our success will be measured by the degree to which we materially improve the lives of remote, rural and disadvantaged communities in the region and build capacity for the kind of sustained advocacy and policy action that we’ll need, beyond the life of the Inflation Reduction Act and the current administration,” Keeler said in the press release.

Other environmental justice efforts

Although the University of Minnesota is listed as a partner in the project, Garvey said she does not see the center as a University commitment. Instead, she sees this as a commitment by Keeler and Gabriel Chan, co-principal investigator and associate professor at the Humphrey School.

“It is something that a handful of really powerful, passionate individuals came together to achieve,” Garvey said.

The EPA awarded the Great Lakes center $10 million to address environmental justice issues in its region, according to the EPA press release.

Both the Humphrey School and Extension are providing resources and support to the project, Jeanetta said. Extension was approached because of its boots-on-the-ground experience and work in communities across the state.

Molly Zins, the central region executive director for Extension’s Regional Sustainable Development Partnerships (RSDP), said her program focuses on serving communities in Greater Minnesota that want to work with University collaborators. Approved projects, which vary based on the needs of the community, are partially funded by the University.

The advisory work groups that develop priorities in the region keep diversity, equity and inclusion in mind to create more sustainable and resilient systems for all, Zins said.

Projects in the central region range from installing electric vehicle charging stations in the Ojibwe Leech Lake Reservation to planting more trees to improve forest health, according to the program’s 2023 statewide project list.

RSDP is partnering with the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe in a multi-year project to preserve an outdoor space adjacent to the Leech Lake Early Childhood Development Center, Zins said.

The Leech Lake Nation had “incredible amounts of land stolen from them,” she added. Because of this, they lost some opportunities to practice Indigenous outdoor education.

Previously, the space was considered for other uses and building projects by the tribal council, according to Zins. The childhood center staff and RSDP worked with a graduate student to develop a strong case for using the space for education.

The organization also worked with a landscape architect to design the space and with an Ojibwe language student at the University to incorporate the language and culture into outdoor activity guides, she added.

“This is one small way in which the University can help contribute to providing a space and some of the teaching tools to bring that back to the participants in the early childhood center,” Zins said.

Other environmental justice efforts by the University community receive less support from the University.

Kat Cantner, an outreach and science coordinator in the N.H. Winchell School of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University, said she has been working with graduate students to organize a workshop focused on environmental justice and forming relationships between the University and the community.

It takes about a year and a half for her and other organizers to plan the workshop and get the necessary funding by applying for grants.

Relationships take years to grow, so the biggest question for them is how to make the event sustainable, Cantner said. They do not have the financial backing to figure out how to make that happen yet, she added.

“The answer is no,” Cantner said when asked if the University supports her efforts. “It is still very much driven by individual interests of individuals in the department.”

Caleb Fravel is a freelance writer who reported this piece as a class final.