The University of Minnesota has seen declines in enrollment for language programs, mirroring a national trend.

Despite foreign language requirements in the College of Liberal Arts (CLA), the University is no exception to the trend. Faculty from language departments say they are hopeful it will reverse at some point, but when that might be is uncertain.

Four-year institutions saw a 16.6% decrease in language enrollment between 2016 and 2021, according to the Modern Language Association.

A major driver of enrollment in language courses at the University is the foreign language requirement in CLA. According to CLA’s webpage on second languages, the college requires students pursuing a bachelor of arts or a bachelor of individualized studies to take at least two years of a foreign language.

Mandy Menke, director of language programs for Spanish and Portuguese studies, said enrollment in 1000-level courses decreased proportionally with enrollment in CLA. Enrollment in CLA is down nearly 10% from pre-pandemic levels, according to data from the University’s Institutional Data and Research webpage.

Menke said part of the value of language requirements is that they allow instructors to decenter students’ perspectives and introduce them to new cultures and ways of thinking.

“When you decenter your perspective and think about your relationship to others, you really have that opportunity to think about, ‘Who are you,’ and how do you fit within this bigger world that we’re all living in,” Menke said.

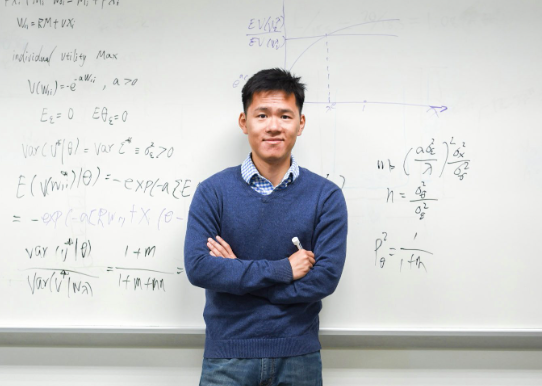

Federico Fabbri, the director of language instruction for Italian, has been teaching languages for the past ten years and did his dissertation on the enrollment crisis for languages in higher education. He said the decrease in enrollment nationally comes from several factors, some of which universities cannot counteract.

Enrollment trends behaved cyclically over the past two centuries and languages normally see cycles of growth and decline, Fabbri said. However, this recent decline is larger and has taken longer than previous declines.

According to Fabbri, the decline began around the financial crisis of the late 2000s and was exacerbated by the shift in colleges and universities toward STEM fields.

“The fact the language programs are declining now does not imply that that cannot change again, hopefully, in the near future,” Fabbri said.

Fabbri said universities around the United States need to do more to make themselves relevant and adapt to the interests and needs of their students.

In terms of enrollment for degrees in foreign languages, Menke said the number of majors in her department has seen a decrease, but the number of minors has been increasing. It varies, but the same trend is present in other languages.

Menke said she believes the shift in majors and minors is connected to the shift in how society views the purpose of a college education. Students picking up majors for a specific profession might not see value in a Spanish major, but a minor can be earned with a smaller workload.

Helena Ruf, the director of language instruction in German, Nordic, Slavic & Dutch, said there’s a difference between students enrolled in lower-level courses and higher-level courses. A greater level of engagement is expected once students enter an advanced curriculum.

One of the readiness goals of CLA is “written and oral communication,” according to Ruf. Language courses teach students to communicate and get their message across even though they do not know everything.

“It’s kind of cliche, but I feel like it opens doors to things,” Ruf said.

Ruf said that when she was a college student, she tested into the fourth semester of German and did not want to continue learning a foreign language. A year and a half later she decided to study abroad in Germany.

“Here I sit now with a PhD in German linguistics teaching German,” Ruf said. “You don’t know where life is going to take you, and we’re giving you something that could be very valuable.”