The study of crime and punishment within the University of Minnesota system varies greatly by campus, with each program tailored to a different set of career opportunities post-graduation.

The Twin Cities program is particularly unique for its foundation in sociology and research. Alternatively, the Crookston, Morris and Duluth programs offer course content leading graduates to more traditional careers in law enforcement.

Twin Cities

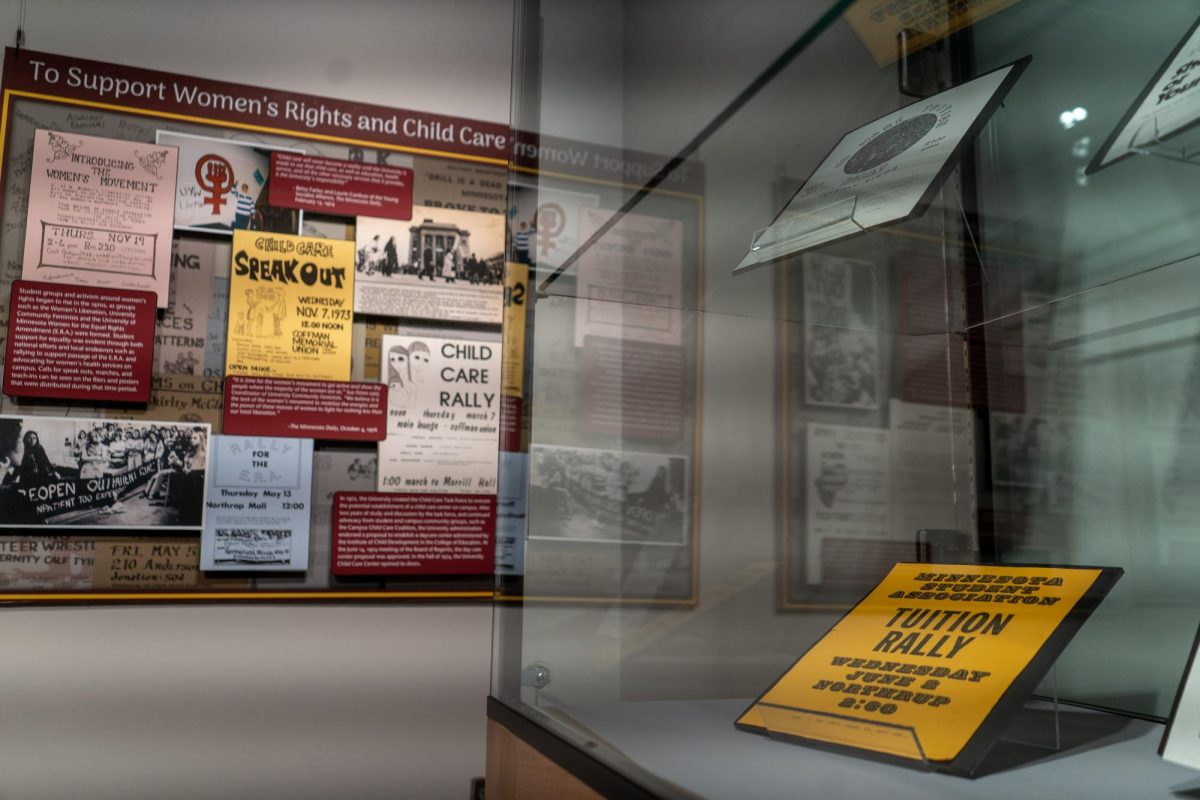

The murder of George Floyd in 2020 had more of an effect on the students who entered the program than the faculty because of the department’s history of research on racism in the criminal justice system, according to Michelle Phelps, an associate professor in the Sociology of Law, Criminology and Justice (LCJ) Department.

“None of us who are on the faculty saw that and were shocked,” Phelps said. “All of us saw it and were like, ‘Oh, that’s happening again.’”

Phelps said the major used to be called ‘Sociology of Law, Criminology and Deviance,’ but the department changed it to ‘Justice’ in response to undergraduate criticism following Floyd’s murder and to better represent how the faculty teaches the curriculum.

According to Phelps, criminology is an interdisciplinary field that includes contributions from sociology and several other fields, while criminal justice programs involve hands-on training that prepares students for law enforcement jobs.

Phelps said all faculty within LCJ have doctorates in sociology, though not in criminology or criminal justice, giving them a more structured approach to crime and criminality.

“It’s much more about, you know, how have definitions of crime changed over time?” Phelps said. “How does who’s in power shape what’s understood as crime or not crime and how it’s punished? And what are the implications of that for inequality?”

Bobby Bryant, the coordinator of undergraduate advising for the Department of Sociology, said there are currently 450 students enrolled in the sociology major. He said the department has seen a decrease in enrollment from the previously consistent 600 to 700 student enrollment, a change he attributed to the national decline in college enrollment.

Of the students in the sociology department, Bryant estimates the split between general sociology majors and LCJ majors is 60-40, favoring LCJ.

LCJ professor Joachim Savelsberg believes approaching crime and punishment from a sociological perspective, as the Twin Cities campus does, is the best way to teach about crime. He said this is because issues of crime, punishment, race relations and legal practices are embedded in social inequality, political processes and legal practices.

“In other places, there’s variation too, and there are some programs that are really very applied,” Savelsberg said. “We ironically refer to those courses as handcuffs one and handcuffs two.”

Crookston

The University’s Crookston campus is the only campus to offer a discrete criminal justice degree, with both online and offline options for students, according to its website.

The degree program is the only one in the system that is Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST) certified. According to the Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers, POST certification requires the programs and workshops to be developed with the guidance and support of law enforcement agencies and experts.

David Seyfried, a senior lecturer at the Crookston campus, explains that the POST certification of their criminal justice degree program allows students a direct pathway into a career in law enforcement post-graduation.

After a student finishes their degree and completes a practical skills course, they are eligible to take a licensing exam, the completion of which gives them eligibility to get their peace officer licensing through the state of Minnesota upon recruitment to a department.

Seyfried said Crookston’s local police department was not the only agency affected by the pandemic’s aftermath, and their criminal justice program was not the only educational program affected.

“Unfortunately, and this is reflected at programs across our state, we are seeing a declining enrollment in people interested in this field,” Seyfried said. “At a time when we have more openings for police officers, at a time when we have a shortage like I haven’t seen in my career, we have fewer people interested in going into the profession.”

According to enrollment data, the criminal justice program has seen rising enrollment overall since the campus introduced an online option, but the number of in-person students has declined from 29 in 2020 to 16 in 2023.

“If we tick back maybe eight to 10 years ago, we probably had double that. We were at about 100,” Seyfried said.

Morris

The University’s Morris campus offers criminal justice as a subplan under their human services degree, the campus’s website reads.

According to Tim Lindberg, the human services discipline coordinator, the addition of subplans is relatively new. It was implemented around six years ago during an overhaul of the program in an attempt to give students the ability to specialize in a field within human services.

The human services major is smaller in scale, according to Lindberg, with 50 to 60 students on average in the general major, 10 to 15 of those being in the criminal justice subplan. Within the subplan, Lindberg said around 80% of students typically end up working in a field at least somewhat related to law or law enforcement.

Lindberg added there are technically no human services faculty members at Morris. Instead, human services classes are taught by faculty across a wide range of disciplines from other departments. This, Lindberg said, is in line with the broad and interdisciplinary nature of the program.

“The Human Services major overall is designed to supplement the sort of gaps in between, say, psychology and sociology and things like that for people that really specifically want more training, but still in a liberal arts fashion,” Lindberg said.

Duluth

The University’s Duluth campus offers a Criminology bachelor’s degree which, according to its website, differs from criminal justice and SLCJ because it teaches students about crime control, criminal behavior and crime as a social phenomenon from a critical lens.

Scott Vollum, the head of the Department of Criminology and Sociology, said while there is an influence of the sociological perspective on the way their department approaches the study of criminology, they are still very distinct programs.

“We’re much more interested in teaching them a critical perspective on how they see human behavior when it comes to criminality or deviance,” Vollum said.

Fred Friedman, an associate professor of criminology at Duluth, said a large focus of Duluth’s criminology department, as well as other similar departments across the nation, is on ensuring they are drawing in students who want to go into law enforcement to help their community, not to be in a position of authority.

“That’s the problem, how do we attract the right people? And how do we get the wrong people — that is, how do we give police chiefs and sheriffs more power to fire those folks?” Friedman said.

Friedman said the tendency of police departments to focus on traffic control instead of violent crimes is harming their relationship with community members, as well as their ability to recruit new officers.

“Every time you give a ticket to a law-abiding citizen, you’re making enemies,” Friedman said. “The best people, you know, they want to solve problems and protect people and discourage recidivism.”