It was July 2022 when Karen Ashe, the founding director of the N. Bud Grossman Center for Memory Research and Care at the University of Minnesota, read the article published in Science titled “Blots on a Field?” detailing suspicion from neuroscientist Matthew Schrag about images from the lab.

The Science news story “came as a huge shock,” Ashe said, because the story questioned their main discoveries.

Abeta*56 was the first Abeta oligomer, a molecular complex of a few units, discovered to impair memory in mice, according to Ashe.

It was discovered in laboratory mice within the Ashe lab, and it sparked interest in generating therapeutic antibodies, especially targeting Abeta*56 to improve memory in patients with dementia, according to Ashe. The process took 20 years, with many failures along the way.

The FDA approved a therapeutic antibody called Lecanemab in 2023, the first new treatment approved for Alzheimer’s since 2003, Ashe said.

“Our discovery of Abeta*56 helped spark the research that led to this therapy,” Ashe said.

The article in Science framed this work as being false, Ashe said. The article resulted in her lab losing funding for vital research.

As a result of the publication, the creation of better drugs for people with Alzheimer’s disease was slowed down, Ashe added. All of the main findings published in the past were replicated and proven to be true.

Abeta*56 is a real molecule, Ashe said, not a non-existent one.

“Abeta*56 is a viable candidate to target with therapeutic antibodies,” Ashe said. “Just as we need different vaccines for different strains of COVID-19, we may also need different antibodies for different variants of Abeta oligomers.”

Charles Piller, an investigative story-writer for Science, wrote the initial article speculating the lab’s discoveries and credibility.

“He framed our work inaccurately, implying that our discovery of Abeta*56 had misled the field into developing therapeutic antibodies that didn’t work,” Ashe said.

Images in journal articles were altered, specifically regarding nonspecific bands or marks that were unrelated to the actual experiment, according to Ashe. If they had been related to the experiment, the lab would have not been able to replicate the results.

“Although the changes that were made to the figures were a misrepresentation and entirely unacceptable, they did not affect the main conclusions of the figures themselves or of the paper as a whole,” Ashe said.

Ashe said what the lab member did was wrong and is not supposed to be done in science.

“I trust my colleagues and do not use imaging software to see if they have altered images of their work,” Ashe said. “My lab is based on trust.”

The suspected lab member left in 2008, according to Ashe.

Looking into the future

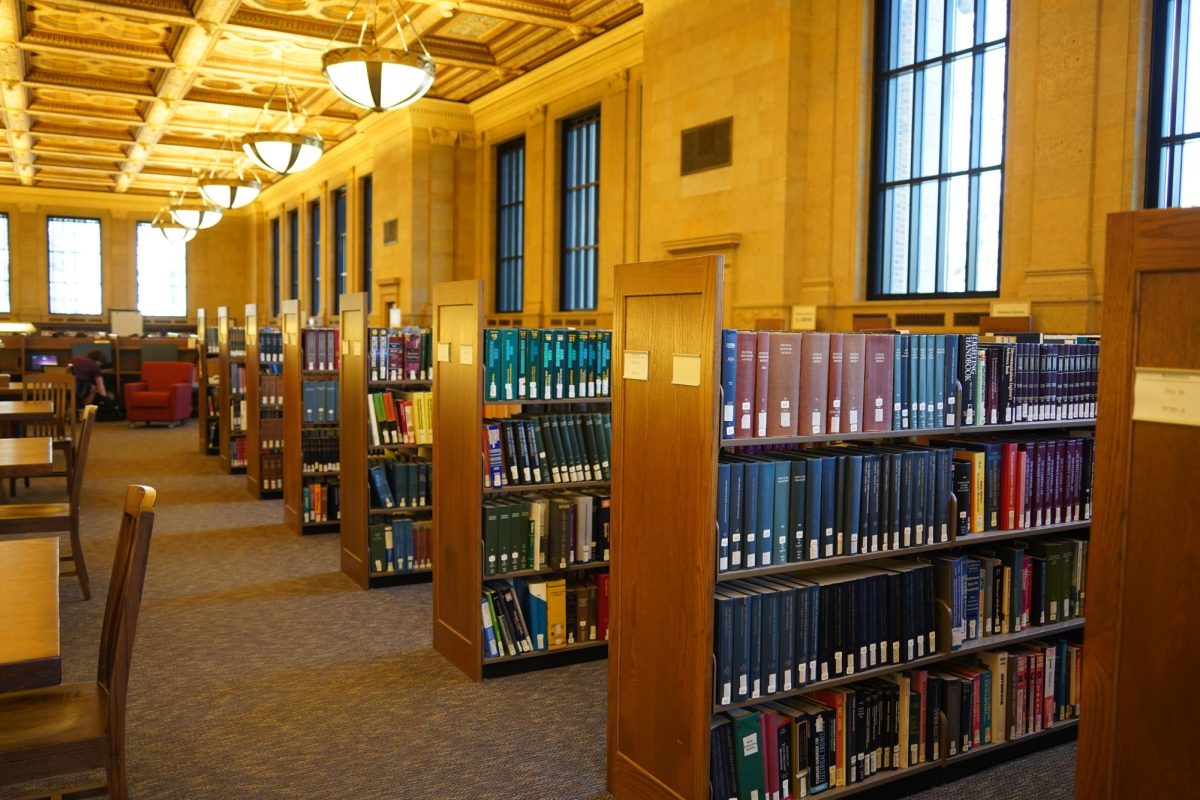

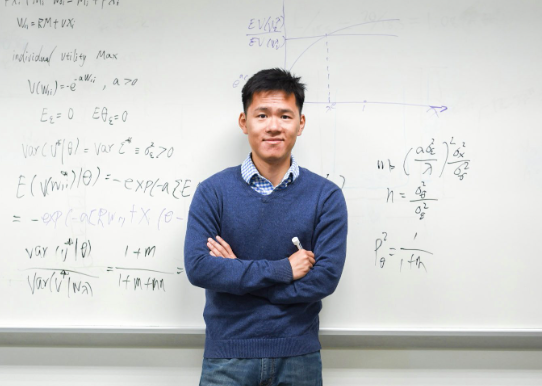

Ashe continues to do work in her lab on Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders, while Dongming Cai is the current director of the N. Bud Grossman Center for Memory Research and Care. Cai stepped into her role in August 2023.

Spending her whole life on the East Coast, Cai said she never considered coming to Minnesota. But, after she was approached by a recruiter for the position and visited the campus multiple times, she fell in love with the collaborative environment.

“This is a very unique opportunity for me to take on this leadership role,” Cai said. “It is aligned with my passion for combining translational research and clinical practice into memory disorders.”

Cai said any questions related to the Grossman Center before her arrival as the new director would be out of her scope since she was not working within any of the labs under the center prior.

The center’s current focus is building a robust clinical research infrastructure while taking advantage of biomarker developments that allow for an earlier diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, Cai said. The department also wants to establish a community outreach program to increase public awareness of dementia.

“I came from the East Coast and many of my patients presented to my clinic much earlier before they even had cognitive complaints, which is not the case in Minnesota,” Cai said.

Minnesotans need better education surrounding Alzheimer’s disease and encouragement to reach out for help so an evaluation can happen, Cai said.

“The needs are high, but I’m here to hopefully build the needed pieces to address the major needs in the community,” Cai said. “We have a great team to make that happen.”

Correction: A previous version of this article misrepresented an investigation into the allegations. Its mention has been removed. Additionally, the first version of the article misstated the year the Science article came out. It was published in 2022.

K

Apr 12, 2024 at 10:47 am

As the other commenter stated, it’s a pretty egregious lapse to not mention that Lesne, the primary subject of the article is still employed by the University. Yes, he left the Ashe lab in 2008 but he did not leave UMN or Alzheimer’s research and the article at the root of this discussion was focused on him, not Ashe.

Why cover this at all if you’re not going to discuss the giant Lesne elephant in the lab?

T

Apr 12, 2024 at 8:18 am

Interesting follow up piece to the fraud story. Curious to see if the author reached out to Lesne, who is also still employed by the university.

Heads up: the Science article was published in 2022, so it’s been almost two years not four.