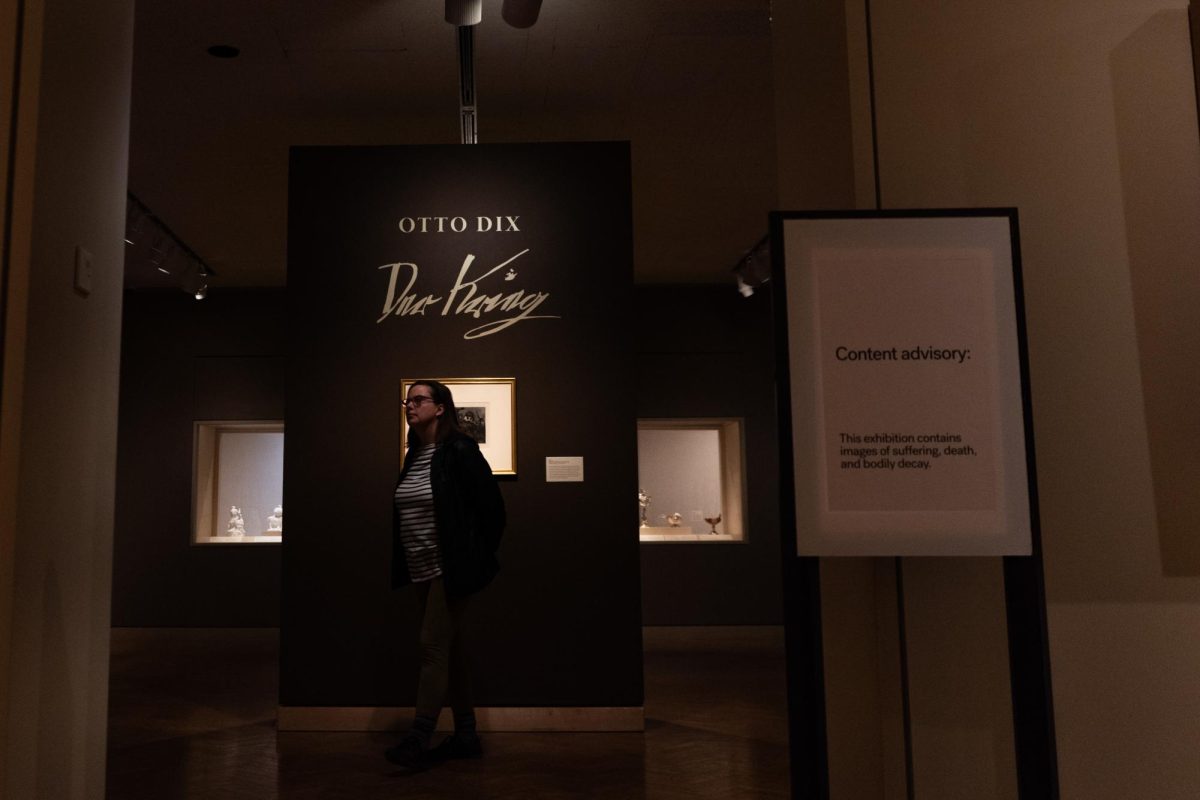

The Minneapolis Institute of Art (MIA) honors the work of German artist Otto Dix in a new exhibition for the centennial anniversary of his portfolio of prints, showing the horrors of the frontlines of war in “Otto Dix: The War Portfolio.”

In a quiet, gray room on the third floor of the MIA, the complete portfolio of Dix is displayed in its entirety, 100 years after its original publication. The series of black and white prints based on his original etchings depict the relentless violence he witnessed in the trenches of World War I as the leader of a machine gun unit in the German army.

The MIA had been home to Dix’s complete portfolio when Tom Rassieur, John E. Andrus III Curator of Prints and Drawings, created the exhibition with his colleague Dennis Michael Jon and drew Rassieur’s attention to the significant anniversary and the portfolio’s subject matter.

“Unfortunately, war is an evergreen subject, and so it seems very appropriate that we show the portfolio,” Rassieur said.

The heavy subject matter is reflected in the muted monotone of the art. Black ink and shadows are used to highlight gaunt faces and ghastly landscapes, each capturing Dix’s memory of his time in the trenches.

“I really came to believe that it reads like a series of 50 PTSD flashbacks,” Rassieur said. “He was on the front lines for three years. So he knew very well what the war was about.”

Returning from war in 1918, Dix’s etchings were commercially unsuccessful during their original publication due to their realistic brutality upsetting viewers. He would later go on to influence the German expressionist movement as he began to experiment more outside of his war subjects.

“He came away from the war feeling cynical, embittered and compassionate. So I felt my job is to give people hand holds and an understanding of what they’re looking at,” Rassieur said. “I wanted this to be a moment when people could confront this first hand and let the artist speak very directly to the visitor.”

And speak it did.

The exhibition room was comparatively mutted to the neighboring period room and Impressionist rooms, with visitors walking silently from piece to piece. The artwork spoke for itself, reflecting the human and environmental cost of the war, as well as the daily experiences of soldiers.

Marina Dorella, someone who went to the exhibit, said that she found the artwork interesting despite the heavy subject matter.

“Many of the prints are very, very dark. Like nighttime, so much so you can barely see them,” Dorella said. “But some of the other ones are very crystal clear, light. So it makes me wonder, you know, if that reflects his memory of those events.”

Rachel Newinski, who was attending the exhibition with Dorella, said the subject matter was timely.

“I don’t think much has changed much in 100 years,” Newinski said. “We see pictures on the news or on social media every day that are in comparison to his memories.”

Some visitors declined to comment on the emotions the exhibition invoked or left immediately upon seeing the subject matter. But those who stayed quietly took in the upsetting scenes and gasped at the depicted subjects.

The brutal prints were a stark reminder of the cost of war and those it impacts.