According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, 46 million turkeys are eaten on Thanksgiving each year.

Turkey is a staple of Thanksgiving in the U.S., and even more so in Minnesota.

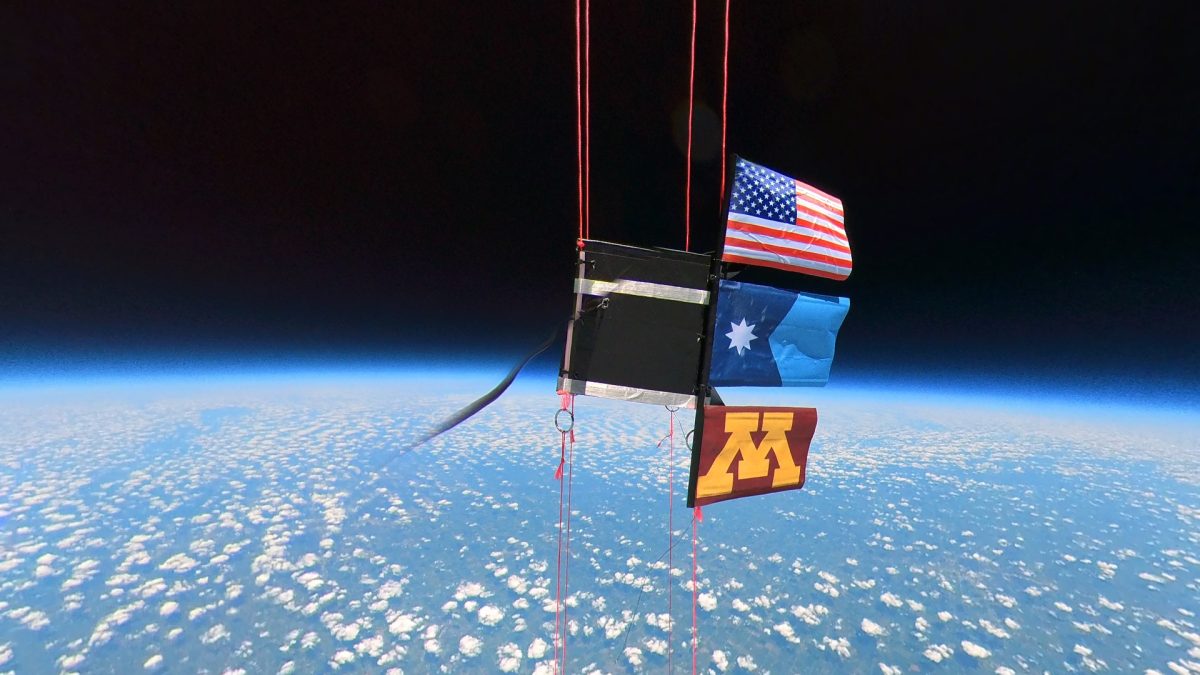

Minnesota is the largest producer of turkeys in the country, making up 18% of turkey production, according to the 2023 Minnesota Turkey Fact Sheet from the Minnesota Turkey Growers Association. The state has more than 600 turkey farmers.

President of the Minnesota Turkey Growers Association and general manager of Falhun Farms Jake Vlaminck said producing turkeys varies by the sex of the turkey.

Vlaminck raises male turkeys, or toms, which are generally used for turkey breast and further processed meats like ground turkey.

Female turkeys, called hens, tend to be sold as a whole bird because of their smaller size, Vlaminck said.

Different turkey growers fit into different niches, Vlaminck said. Some farmers specialize in growing toms, while others specialize in hens or breeding and hatching turkeys.

Hens are inseminated and eventually lay eggs in what is called a laying facility, Vlaminck said. The eggs are put in an incubator for 28 days until they hatch.

When the chicks are a day old, they are separated by gender in a process called sexing, Vlaminck said. Once that step is complete, the chicks are sent to the growers.

“After they hatch, they’ll come to us and they have them already on feed and water,” Vlaminck said. “We just have to put them in the barns and get them used to finding the feed and water in the barn, as opposed to having it right up to their in their tray that they had from day one.”

As the toms grow, farmers ensure the birds have clean water to drink and a comfortable living area filled with wood shavings until they are fully mature, around 12 to 15 weeks old, Vlaminck said. Once they reach maturity they are ready to be slaughtered and further processed for different kinds of meat.

Hens, on the other hand, are raised until they reach a certain weight, Vlaminck said.

“The hens are harvested by weight because they want to have a certain weight that goes into the packaged turkey,” Vlaminck said. “Most people are looking for somewhere between a 12-16 pound turkey because most people have smaller gatherings.”

Carol Cardona, the Ben Pomeroy Chair of Avian Health in the University of Minnesota Veterinary School, said once turkeys are ready for slaughter they are herded from their enclosure into a truck where they are killed.

“They’re quite comfortable in the truck, and then they get off of the truck, and they’ll be stunned, so they become unconscious,” Cardona said.

According to Vlaminck, the turkeys are stunned with carbon dioxide.

Once the turkeys are slaughtered, they are bled out until there is no blood left in their body because people generally do not like the taste of it in their food, Cardona said.

When slaughtering the turkey, it is important to make sure that the bird’s brain is no longer functioning but the heart is still beating and the muscles are still fresh, Cardona said. She added itmakes the meat taste better.

“There’s stages to organ death. And so during the slaughter process, we’re trying to make that meat as fresh as possible,” Cardona said. “We make sure that the brain isn’t feeling anything and the animal is dead, but keep those organs fresh and alive so that the consumer gets the best tasting product possible.”

The meat is inspected by veterinarians before being prepared for retail to ensure that it is safe for consumption, Cardona said.

“Veterinarians inspect those carcasses,” Cardona said. “And even though this bird was acting normal, it might have had a little cold or something, and so that inspector they might say this carcass is not safe to go to the food chain or they might be able to take out the part that had the disease on it, and send the rest of it through.”

Once a turkey is inspected, the meat is cleaned in a series of baths of varying temperatures to ensure it is safe for consumption, Cardona said.

Once the meat is cleaned and free of bacteria, it is sent out for further processing to make products like ground turkey and sausages or is shrink-wrapped and put on the shelves for full birds and turkey breasts, Cardona said.

Over the past few years, Vlaminck said he noticed the trend of “Friendsgiving,” where smaller groups of friends gather for the holiday instead of a large family, influencing the demand for different kinds of turkey meat around the holiday.

“It gets the producers looking more for more Friendsgiving-friendly stuff,” Vlaminck said. “So maybe instead of a whole bird, it might be a boneless breast.”

The Friendsgiving trend has impacted hen growers as well, as farmers need to grow smaller birds, Vlaminck said.

“They want those smaller birds there too,” Vlaminck said. “So they’ll maybe keep them alive a little bit less time, and they might change the feed ration a bit so they grow a little slower.”

Just as Thanksgiving is traditionally a holiday centered around spending time and sharing a meal with family, the business of growing turkeys is also family-focused, Vlaminck said. Falhun Farms is a family business started by his father-in-law and employs many of his family members.

“It’s all family operation, and that’s the way turkey is in Minnesota,” Vlaminck said. “Turkey is family because it’s all family raised. And you think about enjoying turkey together as a family.”