The takeover of Morrill Hall in January of 1969 led to systematic changes at the University of Minnesota.

It has been 50 years since students protested for civil rights following the death of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, and its story is still impactful on campus.

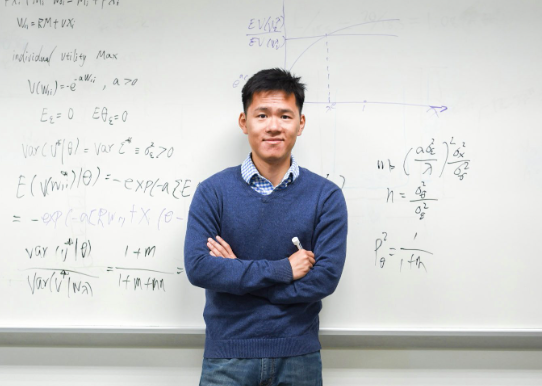

Professor Emeritus John Wright was an event organizer and played a major role in the occupation.

“In April 1968, the country exploded, major rebellions all across the country. More than 100 cities exploded,” Wright said. “So we as students met to decide how we could respond as a group constructively to the assassination and its aftermath. Our group leaders asked me to draft a response that we could then send on to the University administration.”

The demands were deliberated by former University President Malcolm Moos and a task force for eight months. Students felt they were not listened to.

“We then concluded that the progress was totally unacceptable and that we had to take nonviolent direct action and occupy Morrill,” Wright said.

Wright said students were frustrated with the administration.

“At that point in time in this country, higher education was still segregated across the country, even though it’s in the so-called ‘Jim Crow free north,’ there were tiny pockets of black students in even these public universities all across the country,” Wright said. “Black students all across the country, confronting these institutions, public and private, north and south, for the long history of discrimination or white supremacy, in the academic world.”

The occupation lasted from 1:30 p.m. on Tuesday, Jan. 14 until 1 p.m. on Jan. 15 and led to the arrest of five individuals. In the end, protesters met with Moos and discussed their demands.

The University’s African American and African Studies Department (AA&A) was founded post-occupation. The AA&A department was founded in the fall of 1969, following the end of the occupation. Rose Brewer, who worked in the department since 1989, said the 1969 occupation had a lasting impact.

Brewer said Black students were not well represented on campus and “I’d say the curriculum was quite Eurocentric. Part of it was that universities had been disconnected from what was happening in communities, it was an ivory tower dynamic.”

AA&A offers a Bachelor of Arts in African American and African Studies and a graduate minor in Africa and the African Diaspora. Beyond those programs, one key element of the department is the language offering, which teaches Swahili and Somali.

“The language program is an outstanding one, throughout the history of the department,” Brewer said. “Languages represent the student population. We have a large East African student population, and we offer Somali, which is an Eastern African language.”

The program has managed to maintain its presence on campus, an accomplishment that most programs of the same origins have not managed, Wright said.

“Of the departments of African American African Studies and Black studies that were developed over the course of the two decades, and there were more than 400 of those programs, two-thirds of them died out,” Wright said.

The presence of the department is due to support from the University and its roots, Wright said.

“It’s part of the inherent legacy of the department and it informs what we do,” Brewer said.

Brewer said the legacy of the 1969 occupation is seen in today’s political climate and the recent Morrill Hall occupation on Oct. 21.

In October, Wright received the University’s Outstanding Achievement Award, for his activism throughout the years. He said this fight did not begin in 1969 and certainly did not end in 1969.

“The department is grounded in the history, we’ve certainly extended beyond that, but we are very aware of the political moment,” Brewer said. “Our department has students who have been involved in the political struggle currently. Just four or five years ago there was an uprising surrounding the George Floyd murder, so these issues are not just in a historical context, the legacy continues in the current moment.”

KG

Dec 13, 2024 at 1:16 pm

Sam, Hamas-enabling terrorists like you and Faculty for Justice in Palestine (your friend Gallope is a member) continue to distort reality. Hamas committed genocide on October 7, 2023. Hamas uses its own people as human shields and cannon fodder. Hamas is to blame for all the death and destruction in Gaza and Israel. You are to blame for enabling Hamas terrorists.

Sam

Dec 12, 2024 at 9:10 am

So, KG, do you have posters of IDF members on your bedroom wall? You sound like such a child in your comments, it wouldn’t surprise anyone.

Kudos to Gallope and other commenters who have seemingly effortlessly drawn you out over the last year so we can all read about your ridiculous ideas of Judaism. Israel desperately wants to be a faux empire, to dominate with violence and propaganda, relying on fools and tools like you to perpetuate the myth.

KG

Dec 11, 2024 at 10:34 am

Michael, I see that you and facultyhere discuss human rights and compassion in Judaism. You and your friends at Faculty for Justice in Palestine use this talking point to distract from Hamas’s genocide against Israel on October 7, 2023. Let’s not forget the reality of that day: Hamas terrorists crossed a peaceful border, attacked a music festival attended by young people, and obliterated Israeli villages—brutally murdering 1,200 people, most of them civilians. Women were systematically raped and tortured, defenseless children were killed, and people were burned alive in their homes. Hostages, including children, were taken by Hamas and remain hidden in Gaza’s tunnel network to this day. That was genocide. Yet, concern for the human rights and compassion of Jewish victims doesn’t seem to trouble you much.

Israel, by contrast, has consistently shown consideration for human rights and compassion, even in the midst of its war against Hamas. For example, today, after Hamas launched rockets into Israel (a persistent threat), Israel urged non-combatant Palestinians to evacuate targeted areas before responding militarily.

Michael, as a student of religion (this seems to be a new interest of yours), perhaps you can enlighten us: What human rights and compassion were Hamas terrorists observing on October 7, 2023, when they massacred innocent Jews? And what human rights and compassion does the Islamist ideology of Hamas display when it uses its own people as human shields?

facultyhere

Dec 11, 2024 at 7:31 am

Gallope is right, KG. You’re really, really under a veil on this. We won’t stop pointing it out and hoping, sincerely, that you shift your focus and energy to the version of Judaism built upon human rights and compassion for the other. You think about that and see if you don’t feel a little better.

Michael Gallope

Dec 10, 2024 at 10:15 pm

KG, you’re rationalizing Israel’s genocide against Palestinians. We won’t stop pointing that out. Like I said, maybe someday you’ll rediscover the version of Judaism built upon human rights and compassion for the other.

KG

Dec 9, 2024 at 10:06 pm

Facultyhere, on October 7, 2023, 3,000 heavily armed Hamas terrorists crossed the border into Israel, a democratic nation, massacring 1,200 people—including women and children—and taking 250 hostages, including women and children, back to Gaza. In Gaza, an estimated force of 30,000 terrorists anticipated the Israeli counterattack. These fighters embedded themselves among Palestinian civilians, using them as human shields, and hid within an extensive network of tunnels. These hundreds of miles of tunnels, with thousands of concealed openings, turned Gaza into a heavily fortified zone. Uncovering these hidden tunnels to reach the terrorists has contributed significantly to the damage in Gaza. Actually, Israel does not possess enough explosives to destroy the entire tunnel complex. Many tunnel openings are only being sealed to prevent reuse by Hamas.

The Hamas-controlled Health Department has reported inflated casualty figures that fail to distinguish between terrorists and noncombatants. According to the IDF, approximately 17,000 terrorists have been killed—a ratio that demonstrates a level of restraint uncommon in urban warfare by Western armies. Israeli soldiers are paying a heavy price in Gaza every day. If Israel prioritized minimizing its own casualties over safeguarding Palestinian civilians, the loss of Israeli soldiers would be significantly lower. Compounding the tragedy, Hamas is attempting to replenish its depleting ranks by recruiting 14- and 15-year-olds, effectively using child soldiers. These are the same children indoctrinated in Hamas-controlled kindergartens, where hatred is systematically taught from a young age.

If Hamas had not initiated their genocidal attack on Israel, there would be no war in Gaza today. Tens of thousands would be alive today. Think about that.

KG

Dec 6, 2024 at 11:27 am

Facultyhere, on October 7, 2023, 3,000 heavily armed Hamas terrorists crossed the border into Israel, a democratic nation, massacring 1,200 people—including women and children—and taking 250 hostages, including women and children, back to Gaza. In Gaza, an estimated force of 30,000 terrorists anticipated the Israeli counterattack. These fighters embedded themselves among Palestinian civilians, using them as human shields, and hid within an extensive network of tunnels. These hundreds of miles of tunnels, with thousands of concealed openings, turned Gaza into a heavily fortified zone. Uncovering these hidden tunnels to reach the terrorists has contributed significantly to the damage in Gaza. Actually, Israel does not possess enough explosives to destroy the entire tunnel complex. Many tunnel openings are only being sealed to prevent reuse by Hamas.

The Hamas-controlled Health Department has reported inflated casualty figures that fail to distinguish between terrorists and noncombatants. According to the IDF, approximately 17,000 terrorists have been killed—a ratio that demonstrates a level of restraint uncommon in urban warfare by Western armies. Israeli soldiers are paying a heavy price in Gaza every day. If Israel prioritized minimizing its own casualties over safeguarding Palestinian civilians, the loss of Israeli soldiers would be significantly lower. Compounding the tragedy, Hamas is attempting to replenish its depleting ranks by recruiting 14- and 15-year-olds, effectively using child soldiers. These are the same children indoctrinated in Hamas-controlled kindergartens, where hatred is systematically taught from a young age.

It is critical to note that if Hamas had not initiated their genocidal attack on Israel, there would be no war in Gaza today. Tens of thousands would be alive today. Think about that.

Hamas has openly promised more atrocities akin to October 7th. If you believe that Jews in their homeland will acquiesce to being murdered or violated, think again.

facultyhere

Dec 5, 2024 at 8:47 am

As somewhat of an outsider to all this, I read KG’s comments and I wonder, if all that is true, and I have no reason to believe it’s not even though KG sounds both very rigid but also somewhat unhinged, if everyone knows these secret doors to underground tunnels exist, why does Israel keep killing civilians instead of collaborating with them to gain access to these trap doors in children’s bedrooms, mosques and schools? What is stopping the IDF from choosing to close the tunnel access when they find it but leave the humans alive and the neighborhood unbombed?

The more KG tells us about all the access points being in civilian areas, the more it looks like Israel cares even less than Hamas about who/where they bomb. KG is telling us that neither Israel or Hamas cares about killing non combatants but at the same times wants us to believe that only Hamas is at fault. It makes no sense, even for war.

Every year since the late 90s, the U.S. has sent billions of $$ in military aid to Israel. Without that $$ there would be no or almost no bombing because Israel doesn’t have enough of its own $$ to carry out all this crazy. There is plenty of blame to go around; it’s not just Hamas that is deeply in the wrong here.

As Gallope so well put it, we are witnessing “a horrific perversion of Judaism, a religion centered in principles of social justice and service to human flourishing.”

KG

Dec 4, 2024 at 10:41 pm

Michael, I was wondering why you suddenly decided to join this thread. Then it hit me—you didn’t sign the November 25 Op-Ed. You know, the one where your Faculty for Justice in Palestine colleagues accused President Cunningham and UMN of using “Islamophobic rhetoric.” Why not? Ah, yes—you’re a CLA Dean. Criticizing the UMN administration publicly wouldn’t look great for your career, would it? Signing that Op-Ed might have gotten you fired as Dean.

So here you are now, chiming in to signal to your FJP friends that you’re still an active enabler of Hamas. I see you’ve been busy calculating Israeli munitions. Are you also keeping track of the number of Hamas rockets fired at Israel? Spoiler: it’s over 12,000. That’s an average of 1,000 rockets per month or more than 30 per day. Or perhaps you’re calculating the miles of military tunnels Hamas has dug beneath residential areas? Spoiler: it’s at least 500 miles, with some estimates much higher—no one knows for sure since all the tunnels haven’t been uncovered yet. These tunnels serve every conceivable military purpose, yet none are for protecting Palestinian civilians. As Hamas itself has stated, protecting Palestinians is the job of the United Nations, not Hamas.

While you’re at it, maybe you’d like to share how many tunnel entry and exit points Hamas has built? Spoiler: 4,200 and counting. These are hidden in civilian homes, under trap doors in children’s bedrooms, inside mosques, schools, and playgrounds. Hamas doesn’t care that turning civilian areas into military targets puts Palestinian lives at risk. In fact, for Hamas, the more Palestinian noncombatants who die, the greater the international pressure on Israel (from people like you) to halt its operations—allowing Hamas to remain in power and rebuild for future attacks.

Remember this: Hamas attacked Israel on October 7, 2023. Hamas is responsible for all the death and destruction that has followed. Israel is fighting against Hamas, not the Palestinian people. You should be protesting against Hamas. But your ideological blinders and obsession with Israel won’t let you see that truth.

Michael Gallope

Dec 3, 2024 at 12:10 am

KG, these are Netanyahu’s talking points from nearly a year ago. Gaza has already been destroyed with the equivalent of 6 atomic bombs (85000 tons of explosives). Sooner or later you’ll probably have to decide for yourself where you stand on what is actually happening. I regard it as a horrific perversion of Judaism, a religion centered in principles of social justice and service to human flourishing.

KG

Dec 2, 2024 at 11:28 am

Michael, the parameters for a Gaza solution have been clear for months: The Israeli hostages must be returned. The Hamas terrorist regime in Gaza must be disbanded. Hamas leaders must be exiled from Gaza, never to return. Potential destinations include Iran, Turkey, or Algeria (the U.S. has ruled out Qatar—no five-star hotels there). Hamas militants must lay down their weapons. Anyone taking up arms or affiliating with terrorist organizations like Hamas or Islamic Jihad must face the consequences. The Gaza educational system must be reformed. There should be no more Hamas-run kindergartens indoctrinating children or math lessons teaching them to calculate killings of Jews. In 2009, Hillary Clinton herself expressed shock at the terrorist indoctrination materials found in Palestinian schools.

The war continues because Hamas persists in waging it, using Palestinian noncombatants as human shields. Instead of investing the billions of dollars in international aid into education, hospitals, and civilian infrastructure, Hamas built a war machine. They constructed hundreds of miles of tunnels beneath residential areas and near hospitals, schools, mosques, and humanitarian facilities, from which they launch rocket attacks on Israel.

Hamas’s strategy is deeply cynical: they view Palestinian deaths as an asset. The higher the death toll, the more international pressure mounts on Israel to halt its operations and leave Hamas in control of Gaza. This would allow Hamas to rebuild and plan even deadlier attacks on Israelis in the future.

Organizations like UMN Faculty for Justice in Palestine (FLAGSJP), of which you are a member, amplify this pressure. You refuse to acknowledge the October 7, 2023 massacre as genocide. You refuse to admit that this war is Israel versus Hamas, instead misrepresenting it as Israel versus Palestine. By distorting the war’s reality in this way, you are enabling Hamas’s goals and supporting terrorism—whether you realize it or not.

BRUNO CHAOUAT

Dec 1, 2024 at 9:09 pm

Returning the hostages would prevent more atrocities.

Michael Gallope

Dec 1, 2024 at 5:34 pm

KG, Do you have a red line where Israel’s killing of Palestinians would be too much for you to bear, and no longer justified as “defense” against Hamas’s killings on Oct 7? Are you in favor of Israel annexing and cleansing Gaza and the West Bank? In your view, would killing all 5M Palestinians be justified? Where is your red line? Is there one?

KG

Nov 30, 2024 at 7:33 pm

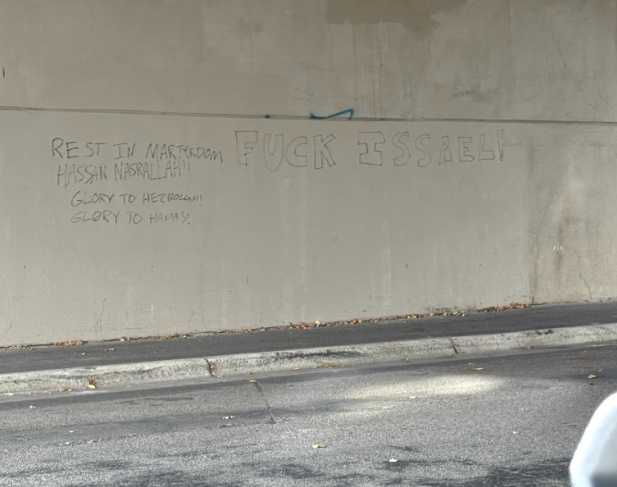

The timing of this article is not about commemorating Morrill Hall 1969. It is a high-profile yet subtle attempt to whitewash the criminal Morrill Hall takeover of 2024. While there may appear to be some surface similarities between the two events, they are fundamentally very different.

Morrill Hall 1969 addressed a domestic issue that was widely understood by all participants. In contrast, Morrill Hall 2024 was orchestrated by a small group of extremists in response to an international conflict where a democracy (Israel) has acted to defend itself against a genocidal attack by Hamas, the terrorist regime in Gaza.

Palestinian propaganda falsely frames the Gaza war as Israel versus Palestinians. This is a lie. There would be no war if Hamas had not launched its unprovoked attack on democratic Israel. Hamas bears full responsibility for the death and destruction in Gaza and Israel. The Morrill Hall perpetrators are not merely ignorant of the facts—they are willfully exploiting the apathy of the UMN student body. Recall that in March 2023, the divestment referendum received only 10% approval from the entire student body, with the vast majority of students declining to participate, even during campus-wide elections.

By staging this takeover, the perpetrators are essentially legitimizing Hamas’ terror-enabling agenda. President Cunningham must take decisive action to prosecute those responsible for the 2024 Morrill Hall takeover. This is the only way to ensure that UMN remains a peaceful campus where students can focus on their education.

DAVID GATSON

Nov 27, 2024 at 3:34 pm

Excellent glimpse into modern U.S. historical event and the students’ response to it. Very good historical and social awareness on part of the Minnesota Daily staff. Please take a little more pride in your punctuality. 01/14/19 actually would have been the 50th anniversary of the original occupation. 01/14/24 would have been the 55th anniversary. This piece was presented on Nov. 26th. I do commend you however, for bringing awareness to this historic incident by submitting the article. You have brought light to something the Star Tribune has UNDOBTEDLY forgotten about. (And they have alumni in their building)