Following President-elect Donald Trump’s inauguration, the Trump administration could roll back on environmental regulations, putting the Boundary Waters Canoe Area at risk.

Removing the regulations would give corporations more leeway to mine in areas that are rich with natural resources, like the Boundary Waters, according to the Sierra Club.

The Boundary Waters are a point of contention in the debate around environmental policy for decades, Friends of the Boundary Waters Communication Director Pete Marshall said. Friends of the Boundary Waters was founded in 1976 to advocate for the protection of the area.

The Boundary Waters is federally protected and strictly regulated to ensure its water quality remains clean and people can enjoy the hiking, camping and canoeing privileges it has to offer, Marshall said. The surrounding land is not federally protected, however, and is rich in copper which is highly sought-after land for different mining companies.

According to mining company Antofagasta, copper is used in a variety of industries, including construction, infrastructure, transport and consumer goods.

Mining for copper is detrimental to the environment, Marshall said. The way the metal is spread throughout the ground makes it impossible to mine for it without impacting the world around it.

“It’s not chunks of copper, it’s spread out through the ore body. So that means that when they mine and they get into the ore body, it’s about 0.69% copper,” Marshall said. “Which means you have to essentially crush up 200 to 300 pounds of rock to get just one pound of copper.”

This process uses a lot of energy, but there are also chemical issues that come with mining for copper, Marshall said.

“The danger is that this copper is bonded to sulfide-bearing ores, and sulfide-bearing ores, when they’re exposed to air or water, produce sulfuric acid,” Marshall said.

Because so much ore needs to be crushed to mine for copper, Marshall said there is a lot of waste that is generated that could potentially get into the surrounding water system.

“The ore that the copper is in produces what is chemically battery acid, and that gets into the water system,” Marshall said. “That’s why it’s so worrisome.”

Twin Metals Minnesota, whose parent company is Antofagasta, is interested in mining for copper between Ely and Babbitt, Minnesota, two cities near the Boundary Waters, according to their website.

The state of Minnesota has regulations in place to keep the state’s water clean. Over 77% of voters in Minnesota voted in favor of amending the Minnesota Constitution to protect sources of drinking water and the quality of lakes, rivers and streams in the state in the 2024 election, according to the Minnesota Secretary of State website.

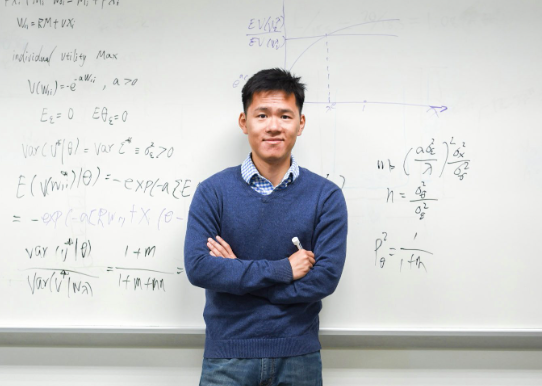

While there is a general consensus in the state that clean water is important in communities closer to the Boundary Waters and other parts of northern Minnesota where mining is prevalent, the division of opinions is much more stark, said Stephen Polasky, a professor of ecology and applied economics at the University of Minnesota.

Some people in these communities make their money in the mining industry, while others work in the tourism industry from canoe outfitting and other outdoor activities, Polasky said.

“In a way, it’s economy versus economy,” Polasky said. “Do you want the mining economy? Do you want a tourism, amenity-based economy?”

There are a lot of protections around the Boundary Waters at the state level that prevent the government from just going there and mining, Polasky said.

“You can’t have a new mine in the state unless it has state permits, and the permits cover things like air pollution and water pollution, and they have to have, you know, an approved Environmental Impact Statement and so forth,” Polasky said. “So it isn’t as if the feds, you know, Trump, can just say, ‘We’re going to mine.’”

What Trump can do, Polasky said, is take off the federal moratorium, or a temporary suspension of a law, to protect the Boundary Waters. While this would be a big step towards mining in the area, there is still the requirement of obtaining a state permit protecting the area.

Mae Davenport, a professor and director of the Center for Changing Landscapes at the University, said treaties with Indigenous communities in the area also protect the Boundary Waters and surrounding areas like the Superior National Forest.

“The Superior National Forest signed a co-stewardship agreement with the boys for Fond du Lac and Grand Portage bands, as well as the 1854 Treaty Authority,” Davenport said. “Which is also just further affirmation that these Ojibwe tribes and the inter-tribal organization are the original stewards of the land, and they have rights that they have retained to access those lands and that those were protected, and so that stewardship agreement just sort of also puts into priority the tribal treaty rights.”

The 1854 Treaty Authority protects the tribes’ right to fish and hunt in the area, according to their website. It also aims to protect and enhance the wilderness and resources outlined in the 1854 Treaty Area, including the Boundary Waters.

Just as the state needs to abide by the treaties, so does the federal government, Davenport said.

“The U.S. federal government and the states have trust responsibilities to tribes that date back to the 1850s to protect these lands and waters and to protect treaty rights, which includes the rights of tribal members to hunt, fish and gather in these areas, and that protects those areas as well,” Davenport said. “So a singular president or an authoritative government cannot terminate those treaties or violate those treaties, just like they can’t terminate or violate the U.S. Constitution.”

Recently, the transition between presidential administrations led to differences in policy for mining in protected areas, Marshall said.

The Obama administration prevented coal mining leases on public lands and started a two-year study investigating what copper sulfide mines would do to the area near the Boundary Waters, Marshall said. Once Trump came into office, he revived the leases Obama prevented and canceled the study on copper-sulfide mining, which the Biden administration later reversed.

“It’s a lot of back and forth,” Marshall said. “Currently, Twin Metals does not have the mineral leases it needs to open a mine, and there was a 20-year mining ban on federal land in the Superior National Forest, so we had pretty strong protections against these potential mines near the Boundary Waters.”