When Swedish, Norwegian and Danish immigrants first set foot in Minnesota, they came for the promise of land and opportunity, but they remained determined to preserve their culture and traditions.

Nearly 150 years later, Scandinavian cultural centers are living proof of how early settlers shaped Minnesota’s identity.

Today, about 43% of Minnesotans who reported multiple ancestry identify as Scandinavian, according to the 2023 American Community Survey.

Evidence of the state’s Scandinavian roots is easy to find. From Viking fans cheering “Skol”— a word derived from the Scandinavian “Skål,” meaning “cheers,” — to towns like Lindström, unofficially heralded as “America’s Little Sweden,” Minnesotans take great pride in celebrating their Scandinavian heritage.

Many Scandinavian-American Minnesotans joke that it was only natural for early Scandinavian immigrants to settle in Minnesota in the 1850s through the 1930s. After all, with its frigid winters and the myriad of lakes, it must have looked just like home.

Although a common misconception, this was not the case, according to Lily Obeda, a teaching specialist in the German, Nordic, Slavic & Dutch Department at the University of Minnesota.

In actuality, a combination of factors Obeda described as a “perfect storm” led to Scandinavian immigration concentrating in the Midwest.

“If these giant waves of immigration had happened in the 1820s, 1830s, you would probably see all of the Scandinavians in Pennsylvania and Ohio and other places that were not quite so far to the west,” Obeda said. “It was just a function of time and sort of good luck on Scandinavians’ part, but it just so happened to look like home.”

The earliest Scandinavian immigrants to Minnesota starting in the early 1850s were mostly Danish, fleeing religious persecution, according to Obeda. Swedes and Norwegians arrived for different reasons.

After a few good crop years created a crop boom, Swedish and Norwegian farming families were able to have more children and more of those children were able to survive into adulthood. Unfortunately for the younger children, Scandinavian farms were passed down generationally, leaving many unmarried young adults with no farm to inherit and limited land available in their home countries, which led the bravest among them to seek opportunity abroad, Obeda said.

This was further exacerbated by famine in Scandinavia in the 1860s and ‘70s. In 1862, the Homestead Act came into effect, creating a strong pull to the United States for immigrants to whom getting 160 acres of land — much of which was taken from Native Americans through forced removal and broken treaties — seemed like a dream come true, Obeda said.

Cultural heritage remains a defining part of Minnesota’s identity, continuing to influence the state significantly. This legacy is reflected not just in historical records, but in the present day, with Minnesota consistently ranking among the happiest states in the U.S., a mirror of the happiness rankings of the Scandinavian countries.

In the 2024 World Happiness rankings, the three Scandinavian countries, Sweden, Denmark and Norway, all ranked in the top seven. In World Population Review’s 2024 Happiest States rankings, Minnesota ranked third.

Unlike most historical migrations, where long-distance travel was gradual, Scandinavians were able to reach the U.S. relatively quickly using new technology like steamboats. They could then send for family and community members, establishing insular communities that helped preserve their culture, according to Gilbert Tostevin, an anthropology professor at the University.

Chain migration, a social process where immigrants from a specific area relocate to the same secondary destination, could help explain the concentration of Scandinavian “hot spots” throughout the state, Tostevin said.

“With navigating between states and societies that have different languages and different ways of living, migrants are kind of stepping into an unknown,” Tostevin said. “They’re stepping into a game, and they don’t know the rules.”

Tostevin said that for early Scandinavian migrants, having a neighbor from their home village who had already navigated the emigration process could ease the transition, simplifying institutional problems and encouraging chain migration.

Cultural centers

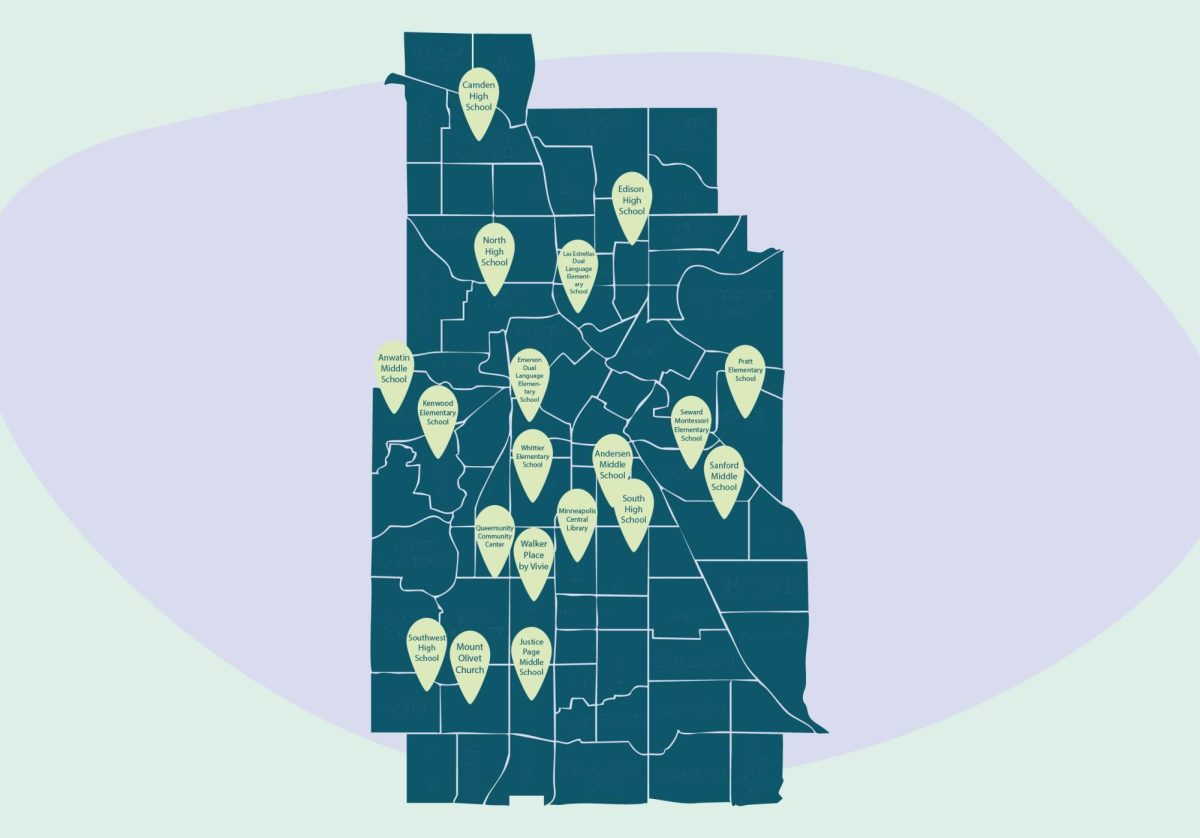

One of the biggest ways Scandinavian influence can be seen in Minnesota today is through the state’s cultural centers. Minneapolis is home to many Scandinavian cultural centers, including the American Swedish Institute, Norway House and the Danish American Center.

The American Swedish Institute (ASI)

The American Swedish Institute (ASI) was founded in 1929, when the Turnblad mansion, the residence of Swan Turnblad, a Swedish immigrant and owner of the largest Swedish language newspaper Svenska Amerikanska Posten, was donated to the institute, according to its website.

Erin Swenson-Klatt, the food and handcraft programs coordinator of ASI, said while ASI originally functioned as a social organization providing important ties for people who came from Sweden, in the last 50 years it has shifted to primarily serving Swedish-Americans and showing Swedish culture to the general public.

As the Arts & Culture programs manager, Swenson-Klatt said she has focused on prioritizing creating and featuring programs to meet the changing needs of its membership.

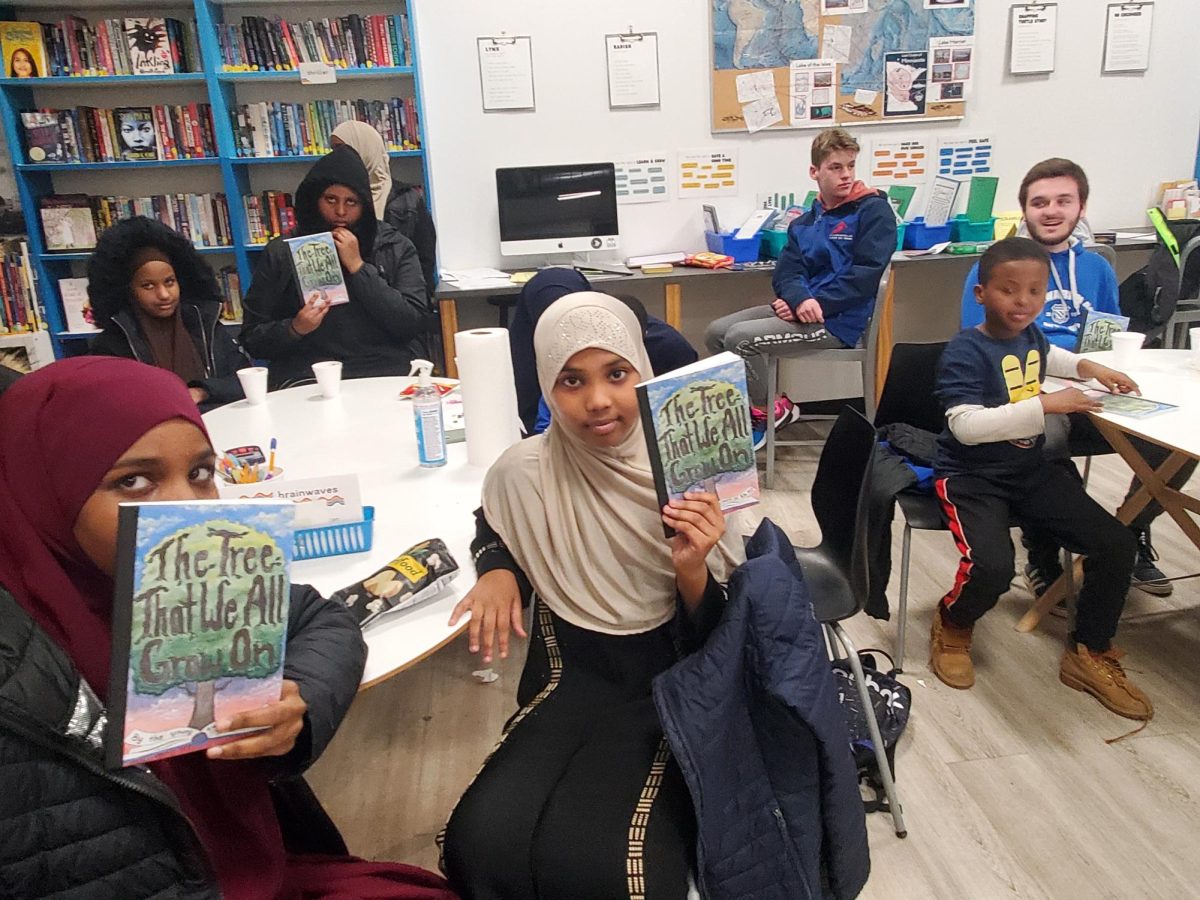

Recently, Swenson-Klatt said this has involved showcasing underrepresented voices of Swedish arts and culture. On June 21, 2025, ASI will open an exhibition featuring work by Salad Hilowle, a Somalian artist who immigrated to Sweden at a young age.

“We live in a world that is totally shaped by migration and cultural exchange,” Swenson-Klatt said. “So wherever we can make more of those connections, find new people to talk to and try out new things, I think we all come away as a stronger and richer society because of that.”

Swenson-Klatt said she does not believe ASI would have been able to flourish as it has had Minnesota not had the concentration of Scandinavian heritage it does.

“I think definitely ASI exists because of the strong history of Scandinavian immigration to Minnesota,” Swenson-Klatt said.

The Danish American Center (DAC)

The Danish American Center (DAC), created in 2005 after the merger of the Danish American Fellowship and Danish senior housing Danebo Home, is an 800-member cultural center meant to share and appreciate Danish culture, according to its website.

Glen Olsen, a longtime member and several-time board member of the DAC, said he was raised connected to his culture, as he was born and raised in Tyler, Minn., which he described as a “happy Danish town” that has kept true to its Danish heritage, albeit in a very American way.

Olsen’s mother was active in many aspects of traditional Danish culture but had a special interest in Danish folk costumes. Olsen said he has been folk dancing since he was young and initially got involved with the Danebo to have a place to dance.

Throughout his time in the first Danebo, which was then encompassed in the DAC, Olsen said he has found that people are typically drawn to the organization through an interest they have in some form of art or cultural activity.

DAC has been a cornerstone of preserving traditional Danish culture, and Olsen said he has seen groups of visitors come to the center and see folk dancing for the first time in their lives.

Despite its membership having in recent history been mostly older people, this year, for the first time in many years, the majority of DAC’s members are 65 and under, according to John Gurley, the vice president of DAC.

Olsen said Minnesota is unique in having a concentration of people with Danish backgrounds, allowing the culture to survive when, in other places, it may have been lost over time.

“We were finding a way to celebrate our heritage because it wasn’t obvious,” Olsen said. “Danes are great assimilators. They didn’t stay Danish very long, and so this is a pretty unusual place.”

Norway House

Norway House is a more recent addition to the keepers of Scandinavian culture in Minnesota, established in 2004 as a contemporary venue to experience Norwegian culture, according to its website.

With many other Norwegian groups in Minnesota, Race Fisher, the development associate at Norway House, said they differentiate themselves by having a unique focus on connecting Minnesotans to contemporary Norwegian culture.

Max Stevenson, Norway House’s chief-of-staff, said like other cultural centers, Norway House is able to bring people a fresh perspective from a different culture, regardless of whether they have Norwegian ancestry. He added this is especially important as each generation becomes more removed from their ancestry.

According to Stevenson, this allows Norway House to attract people who may not have a genetic tie to Norway but are interested in ideas or culture from Norway, such as music, peace-building efforts or art.

“I think a lot of people nowadays are trying to, you know, discover a little bit more about themselves and who they are and their value system,” Stevenson said. “They’re looking for ‘Okay, who am I? Obviously, we’re all immigrants here, and so what is my history?’”

Stevenson said there is an inherent value in learning from other cultures, a belief that has informed Norway House’s collaboration with other cultural centers including the American Indian Cultural Corridor and Latin American and East African communities prominent in the Ventura Village neighborhood in which Norway House is located, a historically immigrant populated neighborhood.

“I think, you know, you gain a lot of perspective seeing how other people live in different cultures, and that really influences you,” Stevenson said. “For those who do not have the opportunity to go abroad, having these cultural institutions are still ways for us to get those ideas of ‘maybe this is how other people do it in the world.’”

Effect on Minnesotan Culture Today

Despite this concentrated early immigration, Scandinavian migration to Minnesota has slowed since that initial boom. Unless an immigrant group has strong ties to the current social world of their home country, they tend to represent a sample from the past, according to Tostevin.

This is reflected in the unique Scandinavian-American culture seen in present-day Minnesota, according to Swedish immigrant and University affiliate Ingela-Selda Haaland. Originally from southern Sweden, Haaland has lived in Minnesota for over 20 years.

Haaland has taught Swedish language and culture classes for 15 years at the American Swedish Institute and this fall has begun to teach Swedish language classes full time at the University.

Since moving to the U.S., Haaland said she has noticed an interesting phenomenon of foods and traditions, especially those associated with the Christmas holiday season, are tied to the identities of Scandinavian-Americans, despite many not being viewed as nationalistic symbols in the countries of origin.

“There’s a crossover between Norwegian traditional Christmas food, Danish traditional foods and Swedish foods, where some might not be part of a Swedish food group, for example, lefse, but they’re very much ingrained in people here who have Swedish heritage, and it has ended up being part of their ‘Swedish foods,’” Haaland said. “In actuality, people don’t eat lefse in Sweden.”

Scandinavian Influence in Modern Times

In recent years, Scandinavian influence in the U.S. has been on the rise. On the social media platform TikTok, where fashion trends are widely created and shared, hashtags like #scandistyle have gained significant traction, with 30.9 thousand posts as of December 2024. #Stockholmstyle has a total of 239.5 thousand posts and #copenhagenstyle has 72.6 thousand.

The popularity of Scandinavian influencers, like Matilda Djerf — a Swedish lifestyle and fashion influencer whose brand, Djerf Avenue, grew into a $35 million brand in just five years of its founding in 2019 — have played a major role in bringing Scandinavian culture and style to the U.S.

August Hansen, a 20-year-old first-year student at the University, said following Scandinavian fashion has been a way for him to connect with his heritage and dressing in that style makes him feel safe, two things he believes are connected.

Hansen, who has dual Swedish and American citizenship, spent six months in Sweden when he was 9 years old to acquire citizenship and to learn Swedish, which he is now fluent in.

“I feel more European than I do American a lot of the time, just because (me and my brother) have been raised with Swedish sensibilities,” Hansen said. “I act like a Swede, I feel more comfortable there than I do here. It’s a huge part of my identity makeup.”

Hansen’s mother, who is Swedish, grew up in the Vermont area, and Hansen said he thinks one of the reasons she moved to Minnesota before having him and his brother was because of the state’s Scandinavian heritage.

“I’m lucky to be in a place that has real cultural heritage that is the same as the culture that I come from, and I think it’s really important that you take some time to look at your family history and understand where you come from,” Hansen said. “Those kinds of generational links are what makes us who we are.”

Ann

Dec 31, 2024 at 5:54 pm

Scandia, Minnesota (northern Washington County), also was a cultural center for Sweden immigration in the 1800s. Visit Gammelgården Museum (in Scandia) to see a collection of historic buildings from the 1800s and learn about immigration in the mid- to late-1800s.

smh

Dec 18, 2024 at 10:26 pm

Immigration, it’s okay if you’re white!