In a perfect utopian world, our own two feet could take us anywhere we wished within our neighborhoods and cities.

Sure, cars can be useful, but in this hypothetical world, we would not be as dependent as we are now.

As a product of suburban Minnesota, much of what I have known has been the opposite. Almost anywhere I went was by car. When I turned 16, learning to drive became a necessity to achieve any kind of independence.

The car-centric norms of my suburban childhood were not a fluke nor an isolated experience. Reliance on cars has been entrenched in American life for almost a century now.

Following the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt implemented several New Deal government initiatives to combat foreclosure rates and stimulate American homeownership. Programs like the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) offered opportunities for Americans to own affordable homes on city outskirts or in newer and less dense suburban developments.

As people began to spread out, walking became less practical and in turn, less prioritized.

This trend continued into the post-World War II era when suburban migration grew. President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, which invested in the Interstate Highway System and connected suburban areas to urban job opportunities.

As long as you still had the means to get to work, with more space and affordable living, the suburbs were an ideal place to be — or so it seemed.

With the rise of suburbia, walkability became an afterthought. Automobiles took precedence over pedestrians or public transportation.

Our car-centric infrastructure has already been built and retrofitting it to prioritize walkability is challenging.

When I came to college, the University of Minnesota campus was a pleasant change of pace. Quite literally.

On and in the area surrounding campus, walking was sufficient enough to get me to where I needed to go, whether that was class, out to eat or to hang out with friends.

Tye Hiltunen, a second-year student, said campus walkability is different from Virginia, Minnesota, where he grew up.

“My hometown is super car-centric and not at all walkable,” Hiltunen said. “What’s great about being on campus is that I don’t have to drive to parking lots to hang out and talk with my friends.”

Hiltunen said college campuses like the University are a prime example of optimal walkability.

“I think universities as a whole should be kind of seen as a model for walkable cities,” Hiltunen said. “We have a lot of natural open spaces. We have places to meet up with people. It’s really easy to get around. There’s a lot of paths and areas that are only for pedestrians too.”

As a student without a car, walkability is largely about convenience. But this is not the only benefit that walkable cities can provide.

Shirley Shiqin Liu, a researcher at the Center for Transportation Studies, said walkable cities also have environmental, public health and social benefits.

“Walking is probably the most eco-friendly mode of transportation,” Liu said. “It reduces greenhouse gasses, it reduces vehicle emissions and mileage and decreases traffic congestion as well.”

Liu said walking can allow commuters to combine their trips to work and daily exercise activities into one.

“It’s the cheapest way to exercise,” Liu said. “There has been research that has found a link between better walkability and reduced obesity rates and improved mental health and well-being.”

Choosing to walk can be a healthier one, but it isn’t a choice everyone has the freedom to make.

“In the U.S., people who are likely to commute to work by walking are typically young people or people from lower-income communities or minority populations,” Liu said. “Walkable cities also help promote access to different economic opportunities across demographics.”

Walkable cities are more equitable cities.

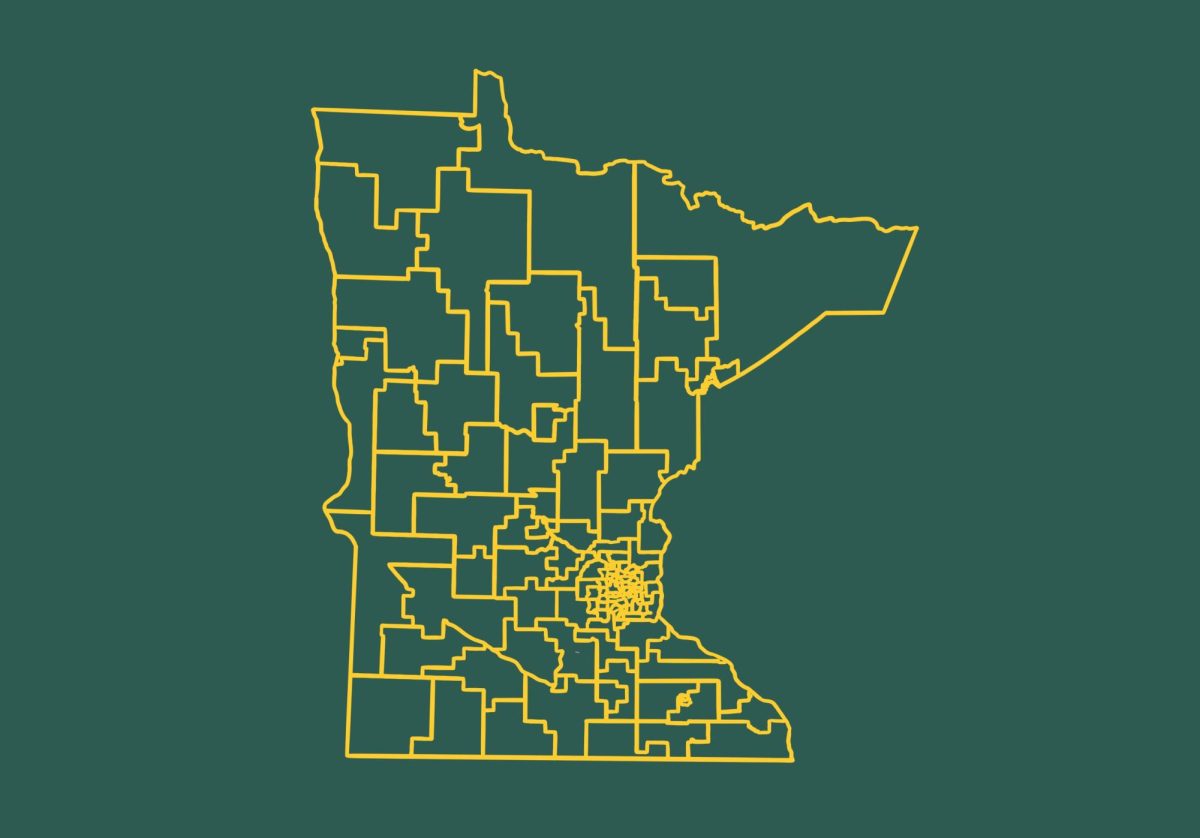

According to Access Across America: Walk 2022, a report published by the Center for Transportation Studies and co-authored by Liu, the Minneapolis metropolitan area ranks 16th across the U.S. in commuting accessibility.

While Minneapolis ranks comparatively high on the walkability scale, many residents will tell you there are still a ways to go.

“When it comes to Minneapolis outside of campus, it kind of feels like you need a car to survive,” Hiltunen said. “We have decent public transportation but there is still a lot of room for improvement.”

The walkability of communities goes beyond mere convenience or cost-effectiveness. While creating sprawling neighborhoods away from city centers may have been economically optimal at one point, our transportation infrastructure has not kept up.

As a result, owning a car is a necessity for many Americans, though not always affordable.

While a walkable world is not achieved overnight, it must be a transition we make. This will require greater investment in public transportation and expanding sidewalks across all regions.

We must learn to prioritize pedestrians, one step at a time.

Lena

Feb 13, 2025 at 9:09 am

A walkable city is probably the best feeling ever. When I lived in a walkable city with access to free public transportation that was throughout the entire city, my mental health increased as well as the relationships I was able to have because I wasn’t dependent on a car. Hopefully, we get more push to reconstruct our cities and end our class divide into a more people friendly environment. It would make us happier as people.

Bob Bosco

Jan 20, 2025 at 9:05 am

The most important ritual of daily American life is being able to park the car as close to the front door of one’s destination as possible. Notice that the parking lots of big box stores, set in spots easily accessible by car, fill up near the doors. Even though every human, healthy or sick, needs exercise, some are given dispensation to park close to the entrances of every building. A monthly program to award effective employees usually means priority parking next to the boss’ car.

In America, people don’t want to walk unless it’s in a walking oriented situation, a hike, hunting, bird watching. Walking as a normal aspect of life isn’t where it’s at.

Daniel

Dec 17, 2024 at 6:27 am

The American push into suburbia and with it, the sprawl of many cities’ limits, is largely due to arbitrary parking regulations enacted in the early 1900s. America now has roughly 9 spaces for every vehicle, which leads to both less usable land for development and also the significant inflation of land value. Similar to this was widely adopted zoning policies for residential lots. Specifically minimum lot size. This minimum lot size led to even more spread and increased land value. Both of these policies, which have now been rescinded in many areas, prevented any new developments from being anything close to walkable areas.