It was late afternoon after a long day of classes, and University of Minnesota student Bianca Llerena made her way home from campus to her house in Como.

She didn’t have groceries at home for dinner. A trip to the store was definitely in need, she’d go shopping before the week was over.

Easier said than done.

Like so many students living in campus-surrounding neighborhoods, Llerena prefers the prices and product options at stores such as Aldi and Trader Joe’s, grocers that aren’t easily accessible to her.

She lives in a campus-adjacent neighborhood without a car and will choose to eat out for the rest of the week until her sister or roommate let her borrow their wheels.

She made a pit stop and bought two slices of pizza for just over $10 at Mesa Pizza, finished her walk home, ate her dinner and boxed up the leftovers as a snack for when she got home later that night.

She then changed into her work uniform and walked a few blocks to start her shift at the Dinkytown Target.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) defines a food desert in an urban area as a location of a low-income population where at least 500 people live more than one mile from a large grocery store.

Roughly 75% of University of Minnesota students live off campus, according to US News and World Report. Only 48% of college students have vehicles to drive.

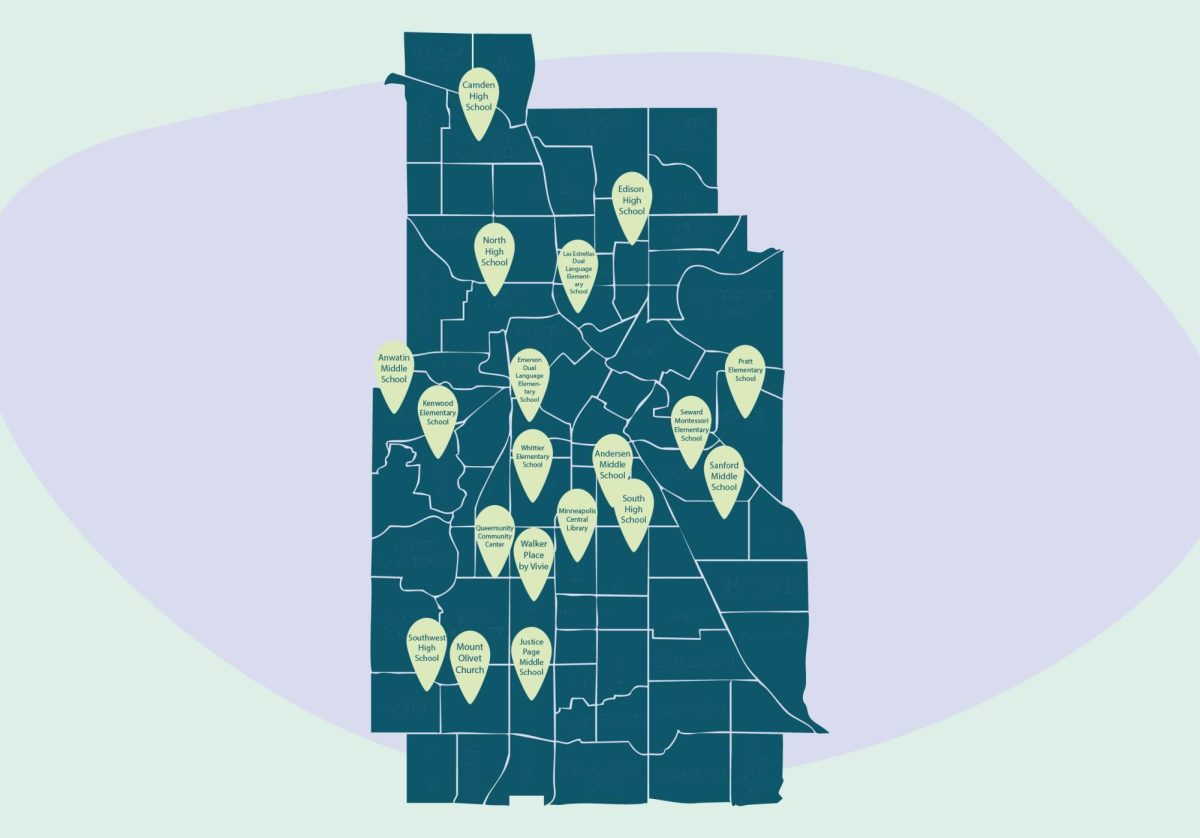

Within Como, Dinkytown, Stadium Village, Marcy-Holmes and Prospect Park, the main neighborhoods surrounding the university campus, there are four small grocery stores less than one mile away. The Dinkytown Target, Adam’s Grocery and Tobacco, Joe’s Market & Deli and Fresh Thyme Farmers Market.

Nearby local businesses such as Mr. Santana, Campus Market & Tobacco and Caspian Persian Bistro & Market are not considered supermarkets because their main product focus is not on goods packaged for consumption at home versus on the premises, according to Law Insider.

Some of the closest full-size grocery stores to the University of Minnesota are Trader Joe’s downtown, 1.3 miles away; Aldi in Ventura Village, 1.8 miles away; and Cub Foods at the Quarry, 2.2 miles away.

If students are dissatisfied with the limited options and high prices of grocery stores within walking distance of their neighborhoods, traveling to these stores is the next step.

For the 52% of university students living without a car, they have no choice but to either subject themselves to the dangers and inconvenience of public transportation to purchase their products, wait until a car is available for them to borrow, or like Bianca Llerena, empty their pockets eating out until they can hitch a ride to Trader Joe’s or Aldi.

In 2024, the Minnesota Daily created a list of basic grocery items from USDA food group guidelines and compared the price total of said list between the Ventura Village Aldi, $31.29; Downtown Trader Joe’s, $35.35; and Dinkytown Target, $36.30.

Of the 14 items on the list, eggs, spaghetti, boxed macaroni and cheese, chicken thighs and tofu could not be cooked inside university dorm rooms that do not allow open heating appliances.

If University of Minnesota students want to buy their groceries from the cheaper prices and wider options of Aldi and Trader Joe’s compared to the Dinkytown Target and other small stores closer to campus, they need to travel to get there.

For students without a car, the bus and the light rail are two transportation options.

While shopping at the Dinkytown Target, University student and Como resident Charlie Alves said she found it very difficult to figure out Minneapolis’ public transit system, especially as a young woman.

Llerena said she does not feel safe carrying her groceries on public transportation.

In 2022, Metro Transit implemented its Safety & Security Action Plan to combat concerning crime statistics. This year, Metro Transit reported a 17.5% drop in reported crime when comparing the second quarter of 2024 to 2023.

Anna Schmid, University of Minnesota Student and Dinkytown resident, said accessibility to affordable grocery shopping is a problem for the entire community, not just a problem for university students.

While shopping at the Dinkytown Target, she said she prefers the prices and product options at Trader Joe’s. Her main concern of food accessibility was for families who live in university-adjacent neighborhoods.

“If they don’t have cars, I don’t know how they get affordable groceries,” Schmid said. “I can barely afford to get groceries, and I’m just living by myself.”

Two small grocery stores in Como, Adam’s Grocery & Tobacco and Joe’s Market & Deli, improve the food accessibility problem for local residents.

Adam’s Grocery & Tobacco provides four small aisles of grocery products and two store cats. Manager Adam Tel said his store tries to stay cheaper than the Dinkytown Target to help students in Como.

“Down there, I feel like it’s more dangerous, more expensive,” Tel said.

Zak Alam, a cashier at Joe’s Market & Deli, said Joe’s provides needs to Como residents in an area where students don’t have many other options.

The University of Minnesota itself is also making an effort to help food insecurity and accessibility for students living on and around campus.

Boynton Health’s Nutritious U Food Pantry is open every other Tuesday and Wednesday inside Coffman Memorial Union in the center of campus. No public transportation or vehicle is required.

The program provides free produce and goods to students without proof of need, only a swipe of their U Card.

Henroy Chacoma, an international student from Nigeria earning his doctorate in statistics, said the food pantry helps him afford food because rent and the cost of living is high in the Twin Cities. He comes to the food pantry every other week.

“It is quite unsafe on the train, which is most times what I use when I want to go to grocery stores. So sometimes I try not to get on the train,” Chacoma said. “The pantry helps a lot. It helps extend the time I have when I don’t have to go to the store.”

Schmid said the university also helped students’ ability to get affordable groceries with the implementation of its Universal Transit Pass in the fall of 2022, making the Metro Transit system of Minneapolis and St. Paul free for students with a tap of their U Card.

Kari White, 56, a Dinkytown resident and frequent Target shopper, said these solutions are beneficial, but there is still a big problem in a lack of grocer options for the large population in neighborhoods surrounding campus.

The Undergraduate Student Government (USG) at the University of Minnesota is working to implement a grocery store on campus in Coffman Memorial Union.

Amara Omar, director of USG’s new food insecurity ad-hoc committee, said a ballot for the store passed a campus-wide vote in the spring of 2024.

Omar said Boynton’s Nutritious U Food Pantry in Coffman is not enough for students experiencing food insecurity, with long lines and understaffed volunteers.

USG’s goals for the on-campus grocery store in Coffman include prices comparable to Aldi, the need for around 15 employees starting at $15 an hour and inclusive halal, kosher, vegan and vegetarian product options.

Volunteer team lead at Boynton’s Nutritious U Food Pantry Jack Lawson said USG’s plans for a grocery store would be a beneficial resource for students, but the food pantry in Coffman would still be a necessity to provide food for students who cannot afford to buy groceries at all.

Llerena said a bus route directly to The Quarry, a strip mall in northeast Minneapolis with a Cub Foods and Target, would also benefit students.

With current public transportation options, it is a 38-minute trip to The Quarry’s shopping center, requiring two different buses with five detours and one delay due to construction.

According to the Office of Disease prevention and Health Promotion, residents in neighborhoods with a lack of accessibility to grocery stores and limited transportation options are at a higher risk of food insecurity.

Univeristy of Minnesota Boynton Health’s 2024 College Student Health Survey reported 21.8% of university students said they worried their food would run out before they had money to buy more. 12.4% said they had experienced a food shortage without money to get more products in the last 12 months.

University students experiencing food insecurity are more likely to have a lower GPA, higher levels of stress, worse sleep habits, patterns of disordered eating and feelings of isolation from their peers, according to Elevance Health.

Dr. Melissa Laska, a professor in the University’s School of Public Health, is leading a study on college hunger, doing research to create working policies and interventions for campus food insecurity relief.

“Our team is deeply dedicated to the notion that no young people should have to choose between their pursuit of higher education and feeding themselves,” Laska said in a news release for the school.

Lael Gatewood

Feb 5, 2025 at 11:29 am

You missed the Hamden Coop on Raymond, a short 87 south bus ride

from Saint Paul Student Center. That route runs from Rosedale in the north, through Saint Paul Campus, to Raymond LRT Station, to a Target in Highland Village, to Aldi on W 7th in the south.