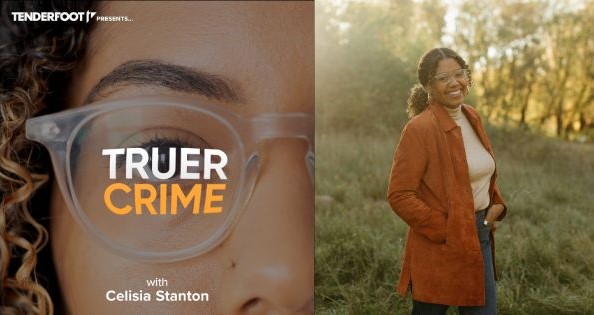

As Celisia Stanton pieced together cat puzzles in the bleak midwinter of 2020, she listened to hours of true crime podcasts, like many of us.

While the stories were addicting and interesting, Stanton said many still lacked crucial details.

“I felt like they were never talking about race, gender, sexuality, the root causes of crime or why crime happens,” she said.

Stanton, at the time, was defrauded of her savings, a crime she said was the straw that broke the camel’s back. After urging from her husband, Stanton started her own true crime podcast, “Truer Crime.” More than four years later, the show is in its second season, and Stanton hopes to shift the genre.

“It’s not a bad thing to say that true crime is entertaining, or that I want my stories to be entertaining. That’s how you get buy-in from people, that’s just psychology,” Stanton said. “It’s really just about what you’re using that entertainment value for.”

“Truer Crime” uses its gripping entertainment value driven by Stanton’s engaging, debate-team-trained narration to reveal the systemic injustices behind true crime cases, ranging from wrongful conviction cases that fell through the cracks to gendered violence on college campuses. Stanton also talks about the injustice in infamous cases like Jonestown.

“Most people don’t know the majority of the people who died in Guyana at Jonestown were Black folks, particularly Black women, and that Jim Jones really forwarded this message of racial and class justice,” Stanton said.

The “Truer Crime” formula is grounded in acutely emotional stories, a far cry from the sensationalized, abstract retellings that are all too common in true crime media.

Another compelling aspect of “Truer Crime” is the inclusion of action items at the end of each episode related to its case or subject matter.

The most recent episode covers the story of Toforest Johnson, a Black man currently on death row for murdering a police officer despite a litany of contradictory evidence. Stanton includes a petition listeners can sign to get Johnson a new trial.

“It’s literally life or death for (Johnson), the best thing we can do is raise visibility for his case,” Stanton said. “Those sorts of things really do make a difference because they put pressure in the right places.”

The realness of “Truer Crime” means each episode is somewhat a heavy listen, but Stanton, a welcoming and kind host, puts content warnings at the beginning, urging her listeners to continue with care.

It starkly contrasts the true crime content on YouTube that University of Minnesota sophomore Ruweyda Ali said she would encounter as a teenager.

“Why are you talking about someone being cannibalized while you’re literally eating something,” she said of the videos.

Ali found herself more fascinated by documentary and forensic aspects of true crime than any sensationalized retelling on YouTube, which she often found weird. She added that victims’ family members would comment on the videos asking for privacy, which was often not respected.

Still, Ali said, “It would be a lie to say that (true crime) isn’t interesting.”

Ultimately, Ali agreed that it matters how true crime stories are told, echoing Stanton in saying many case outcomes depend on who has the resources to solve them, often the police.

“I feel like as Gen-Z, we’ve grown up not to trust cops, but it’s always been a problem,” she said.

Ali also said true crime fans should pay attention to why they’re drawn to that content in the first place.

“I still have a lot of learning to do,” she said. “How you consume true crime matters. There are still humans behind these stories.”

Former University student Summer Knopik said their interest in true crime was an avenue to process their related trauma head-on.

“When I started getting into it, my purpose was ‘How can I protect myself better? How can I be more aware of my situations,’” they said.

Still, Knopik said a lot is still missing from discussions of true crime, particularly the topics Stanton seeks to address in “Truer Crime.”

“It makes me feel better knowing that podcasts like (‘Truer Crime’) exist and that there’s an option to consume media that tells it like it is,” they said.

As humans, we’re naturally drawn to storytelling, particularly individual stories. A morbid fascination with deviance is also a common phenomenon — the chaos of unexpected death and the drama that both precedes and follows it, as Stanton said, is addicting to hear about.

What’s groundbreaking about “Truer Crime” is it seeks to create more trusting communities instead of dividing them through fearmongering.

“I hope true crime can be more nuanced and careful,” Stanton said. “How can these stories be told in a way that guides us towards safer, more trusting communities?”