The University of Minnesota Board of Regents approved a resolution Friday allowing the University president to limit statements from groups of faculty on “matters of public concern.”

This means units — departments, centers or institutes — within the University can only publish statements on political matters at the University president’s discretion. It does not limit individuals from expressing their opinions.

The decision caused concern over academic freedom from University faculty, some of whom participated in a protest with students at the Friday meeting. One protester was arrested for trespassing shortly after the resolution passed.

The resolution also comes as the University is the subject of a Title VI investigation over complaints of antisemitism and scrutiny on University administration for rescinding a directorship offer for the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies.

“(The resolution is) very, very concerning, that sort of very narrowly defines our academic freedom as a right of individuals rather than as a right of collectives of individuals,” said Claire Halpert, a linguistics professor and director of the University’s Institute of Linguistics.

The University’s policies on academic freedom are “only as good as the institution’s willingness to defend people who are coming under attack” for their academic speech, Halpert said. This could be from inside the University or outside perspectives in the community.

“You don’t just solve academic freedom, you have to constantly be enforcing and monitoring and also making sure that the messaging that comes from leadership at the university is 100% rock solid,” Halpert said.

Why did the Board propose this?

Let’s go back to November 2022.

University Executive Vice President and Provost Rachel Croson visited the Academic Freedom and Tenure committee of the University’s Faculty Senate with questions about academic freedom, Eric Van Wyk, current committee chair and computer science professor, said. The committee’s non-urgent task was to examine the Board of Regents policy on academic freedom that had not yet been implemented as administrative policy.

Until the decision to restrict unit statements, Board of Regents policy defined academic freedom as “the freedom, without institutional discipline or restraint, to discuss all relevant matters in the classroom, to explore all avenues of scholarship, research, and creative expression, and to speak or write on matters of public concern as well as on matters related to professional duties and the functioning of the University.”

It did not list specific restrictions on when and how faculty cannot speak about an issue.

The issue of academic freedom became much more urgent following the Oct. 7, 2023 attack by Hamas on an Israeli music festival and Israel’s retaliatory attacks on Gaza when multiple University departments issued statements in support of the Palestinian people, Van Wyk said.

Croson visited the committee again in December 2023 with a draft policy that concerned committee members, Van Wyk said. Croson proposed three options — either the University implements an auditing process for departmental statements, pre-approves all departmental statements before publication or completely prohibits departmental statements.

At its January 2024 meeting, the committee requested the Faculty Senate to allow it to investigate this issue in depth.

“It seemed to be moving very quickly, and it’s an important thing,” Van Wyk said. “We wanted more time.”

In May 2024, former interim University President Jeff Ettinger and Croson established the President’s Task Force on Institutional Speech to develop a policy related to “institutional statements on matters of public concern,” prompted by departmental statements after Oct. 7, 2023.

Van Wyk said there was a lot of good consultation back and forth between that task force and the Academic Freedom and Tenure committee between the task force’s formation and its final recommendations in January 2025. The final report passed a vote in the University Senate 122-8.

The policy put forward by the task force was hailed as a triumph of shared governance during the University Senate meeting, Van Wyk said.

But at its February meeting, the Board responded to the task force’s report with a resolution proposing the University president be the sole authority on institutional statements.

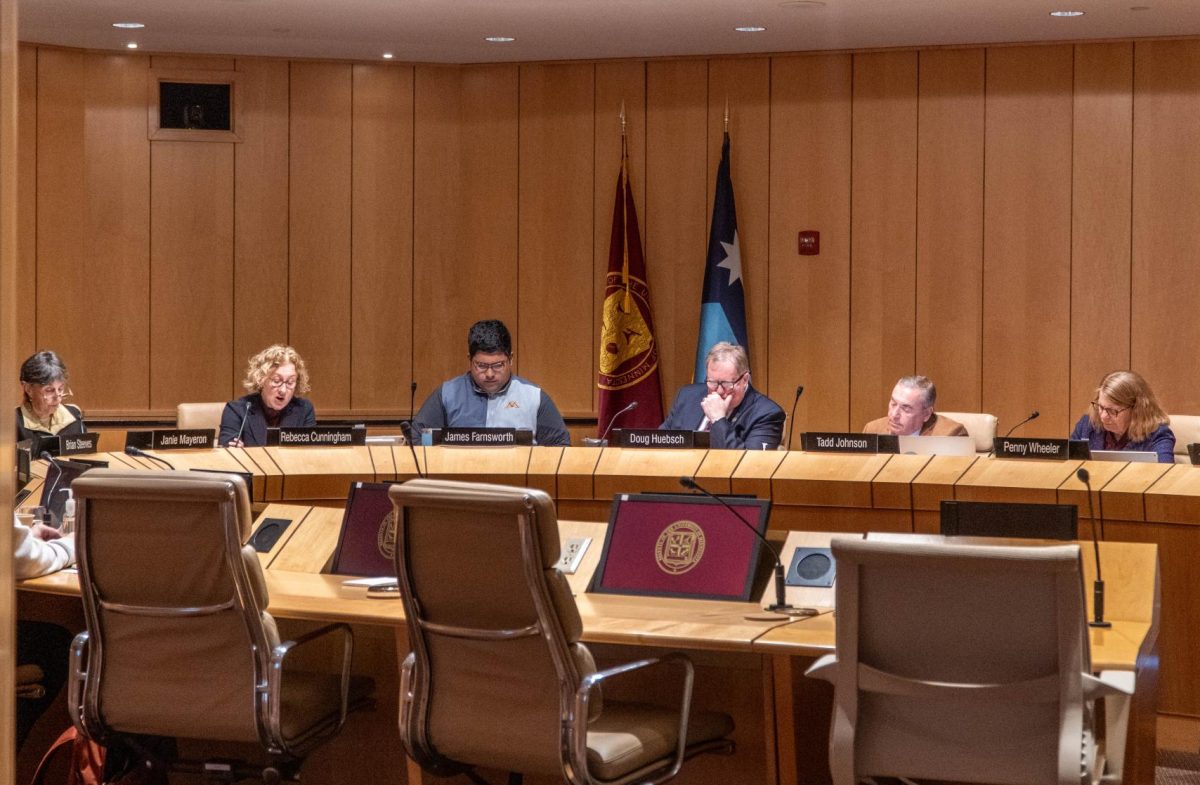

The policy passed by the Board, proposed by Regents Janie Mayeron, Douglas Huebsch and Mike Kenyanya, “flagrantly disregards the consensus of the University Senate,” Nathaniel Mills, an English professor and a member of the executive committee of the University’s American Association of University Professors (AAUP) chapter, wrote in an email.

How does tenure tie into it?

The disagreements over academic freedom are underscored by the issue of tenure, Van Wyk said.

“The whole idea (of shared governance) is the faculty are involved in the governance of the institution. If you don’t have tenure, how freely can you speak about how the institution should be run?” Van Wyk said.

The task force started with the question of what protections exist for the academic freedom of non-tenured faculty, he said.

The answer? “Not much,” Van Wyk said.

The fight over academic freedom started at Stanford University in 1896 when Edward Ross, an economics professor, criticized the railroad industry the Stanford family profited from and later called for the removal of Japanese immigrants from the U.S.

Ross received criticism for expressing political opinions and eventually agreed to resign, including pressure from Jane Stanford, the university president at the time, to fire Ross.

Then, there was no tenure system in place at American universities.

This changed in 1915 when professors from across the country came to form the AAUP. The organization’s 1915 Declaration of Principles on Academic Freedom and Academic Tenure lays out an early tenure system and principles of academic freedom for universities to follow.

“The general thought was that, both in teaching and in research, universities were supposed to serve the public good, and the public good sometimes had to transcend what individual administrations, or people who ran the university, had to say,” computer science professor Gopalan Nadathur said.

The AAUP later clarified and expanded these standards in a 1940 declaration stating that faculty need freedom to research and teach in a classroom, though they should limit discussing controversial matters unrelated to their subject. In making public statements, faculty should be accurate and indicate they do not speak for their institution.

The 1940 statement also states after a probationary period, teachers should have permanent tenure and only be fired “for adequate cause” or “under extraordinary circumstances because of financial exigencies.”

The University’s detailed faculty tenure policy is what gives teeth to academic freedom, said Nadathur, who has tenure and has worked at the University since 2000.

“You can talk about it in the abstract, but unless there is a process that makes sure the loopholes aren’t exploited, it is meaningless,” Nadathur said.

The University is increasingly depending on instructors who are not tenure-track, Nadathur said. A report from a subcommittee he chairs found roughly 40% of all faculty are not eligible for tenure, with the number dropping closer to 30% excluding the Medical School.

One result is that non-tenure track instructors are shying away from new ways of introducing topics to not risk low scores from the end-of-semester Student Rating of Teaching, Nadathur said.

“Those faculty members really felt challenged in carrying out their work in the way they would like to do it,” Nadathur said.

One explanation behind comparatively low rates of non-tenured instructors in the University’s medical school is that the majority are clinicians and are less interested in publishing and applying for federal grants, Clifford Steer, a professor in the Medical School and non-voting member of the Academic Freedom and Tenure committee, said.

For the medical faculty at the University, there is more concern about the federal government cutting grant funding than academic freedom at the institutional level, Steer said.

“People are concerned about whether they’re going to have a job tomorrow,” Steer said. “It’s a little bit spooky out there.”’

Erika López Prater, a former art history instructor at Hamline University in St. Paul, showed an image of the Prophet Muhammad in a fall 2022 class, and school officials decided against renewing her contract after hearing complaints from Muslim students who considered depictions of the Prophet to be blasphemous, Sahan Journal reported.

“Had (the Hamline professor) been in a tenured position, the administrator would have had to engage in a more careful analysis,” Nadathur said.

The Regents policy directing the president to disallow unit statements is an example of someone being influenced by external political pressure and using that to abrogate academic freedom within the University, Nadathur said.

“Some people think of (tenure) as recognition, as some medal,” Nadathur said. “It was never devised to be that medal. It was devised to be a mechanism for protecting academic freedom.”

Israel-Palestine and the Title VI investigation

Pediatrics professor Michael Kyba said the statements published by departments following Oct. 7, 2023 were one-sided and caused concern for some of the Jewish community on campus.

“We have a population of students and faculty who say that these statements are impinging on not just their academic freedom, but their ability to function,” Kyba said.

Kyba, a member of the Academic Freedom and Tenure committee, said the AAUP’s 1915 declaration outlined that the principles of academic freedom should only apply to speech that is academically responsible.

And while the 1915 declaration is not clear on the limits of academic speech, Kyba said ideally peers should judge academic responsibility, sometimes University leadership must step in to regulate — such as with department statements published in the wake of the October 7 attack.

Academic freedom is being used as a defense for academically irresponsible, antisemitic statements published on University websites, Kyba said.

The Gender, Women and Sexuality Studies department released a statement on Oct. 16, 2023, criticizing the University’s investments in businesses with Israeli ties and said Israel’s response to the Oct. 7, 2023, attack was “not self-defense but the continuation of a genocidal war against Gaza and against Palestinian freedom, self-determination and life.”

“Palestine is a feminist issue,” the statement reads.

The statement was cited in a Dec. 9, 2023, formal request by former Regents Michael Hsu and University law professor Richard Painter that the U.S. Department of Education investigate the University for allowing “entire departments to post antisemitic faculty statements condemning Israel, and justifying the terrorist attack by Hamas, on official department websites.”

The U.S. Department of Education first announced in January 2024 that it would launch an investigation into complaints of antisemitism at the University. At the time, the University was one of 99 schools under investigation for discrimination based on shared ancestry, which was made illegal under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The Education Department announced March 14 that it opened investigations into 45 schools under Title VI, including the University.

In an email on March 10, University President Rebecca Cunningham said the University’s leadership team is “strongly committed to enhancing support for members of our community who are Jewish.” The email stated the University recently joined the Hillel Campus Climate Initiative to counter antisemitism.

The University received a failing grade from the Anti-Defamation League’s campus antisemitism report card, last updated on March 3.

Cunningham wrote in the email, “The University will fully cooperate with any reviews or investigations involving these important matters.”

“Instances of mass violence, genocide, ethnic cleansing, war crimes always present the greatest test to academic freedom,” said Michael Gallope, chair of the cultural studies and comparative literature department. “The stakes are existential for the university to maintain and support academic freedom, particularly in times of war.”

University leaders need to voice strong support for the principles of academic freedom to uphold it, Gallope said. He added in instances when academic freedom is violated, administrators need to be held accountable, such as the vote of no confidence in Ettinger and Croson.

Ettinger withdrew a job offer for director of the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies from Israeli scholar Raz Segal, who had received criticism for calling Israel’s actions in Palestine a genocide. Ettinger decided in June, only a few weeks before Cunningham would take over as President.

Halpert said the move was criticized by faculty as an overreach in hiring policy, but the choice to limit what a center director can or cannot say is a threat to academic freedom.

The AAUP released a statement on Oct. 14 condemning the revocation of Segal’s directorship, calling it a violation of academic freedom.

The University’s Faculty Senate approved a vote of no confidence in Ettinger and Provost Croson in June following the decision.

“Academic freedom is upheld when leaders in positions of power voice strong support for its principles,” Gallope said. “We can also support it by raising awareness of academic freedom and its importance to the institution. In unfortunate circumstances when it’s violated, we have to hold people accountable — that’s why we had a no confidence vote.”

A vote of no confidence is a call for leadership change, Gallope said. But that decision is ultimately up to the Regents, he added. Provost Croson did not lose her position due tothe no confidence vote, but Croson announced in early December she would be stepping down from her position after this academic year.

Academic speech and the First Amendment

The University requested around $500 million from the state legislature in 2024 but received only a fraction.

“I think that tends to make the University somewhat risk averse, in the sense of not wanting speech that some legislators don’t like to emanate from the University,” media law professor Jane Kirtley said.

But there are limits on what speech the University can control, Kirtley said.

Under the First Amendment, all speech is protected barring a few exceptions, including incitements to violence, defamatory speech and true threats, Kirtley said.

Embracing a robust idea of academic freedom would help protect the University as an institution from potential liability because individual faculty or groups would be responsible for their speech, Kirtley said.

However, Kirtley said that would not address the emotional or political concerns of taxpayers and legislators offended by certain viewpoints expressed by people employed by the University.

Kirtley runs the Silha Center for the Study of Media Ethics and Law within the University. Centers and institutes are intended to engage with the public on matters of public interest and concern, she said.

“(The Silha Center) deals with issues of media law, free expression, freedom of information, those are all matters of public interest,” Kirtley said. “I’m not allowed to talk about them anymore. That means I can’t do my job, and the Silha Center can’t do its job. From a First Amendment perspective, it’s unconstitutional.”

Units are a more difficult topic, Kirtley said. Some units engage in public-facing research with a priority for public education and engagement while others do not.

“To say that we can’t do that anymore is basically cutting us off at the knees and making it impossible to fulfill a mission that the University has recognized that we have,” Kirtley said.

The limitations on unit statements are “driven largely by, I’ll just say it, cowardice on the part of the University administration,” Kirtley said. “And whether that’s fear of funding, fear of unhappiness by potential donors … you have to ask them.”

PUF funds

Mar 26, 2025 at 7:59 am

Regarding PUF funds, if these funds are redirected at least part of them should be appropriated to benefit Native Americans. These funds are largely derived from land and resources that originally belonged to them.

Impressive reporting, thank you!

Mar 21, 2025 at 3:48 pm

It’s time to start talking about opening up the PUF to offset the cuts we all know are coming.

UMN001

Mar 20, 2025 at 10:49 am

Do you think a department statement which this article referenced on October 16, 2023 is in line the current University of Minnesota’s Board of Regents Policy: Mission Statement Subd. 2. Guiding Principals (bullet #2)? That statement which also helped fuel protests at the UMN have not provided “an atmosphere of mutual respect”. Regarding bullet #2, that statement is not “conscious of and responsive to the needs of the many communities it is committed to serving” which includes Jewish students.

Anonymous

Mar 19, 2025 at 10:34 pm

Executive elites at the University of Minnesota and their regent enablers are fascists. Period. They will NEVER be able to escape that fact.

KG

Mar 19, 2025 at 11:54 am

The Minnesota Daily regrettably fails to identify Faculty for Justice in Palestine (FJP) faculty when they are interviewed. For the record, Nathaniel Mills, an English professor and executive committee member of the UMN chapter of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), is also a member of UMN FJP. Michael Gallope, chair of Cultural Studies and Comparative Literature, is likewise affiliated with UMN FJP.

The core proponents of so-called “academic freedom” are FJP members, bolstered by BDS supporters (and useful idiots). These faculty members, numbering in the dozens, wield outsized influence in hiring and tenure decisions, demanding that candidates demonstrate virulently anti-Israel positions. In classrooms, they perpetuate the false settler-colonialist narrative, demonizing Israel while ignoring historical evidence. UMN FJP dominates several CLA academic units and recently attempted an underhanded takeover of CHGS (Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies).

FJP and BDS faculty consistently disrupt campus life by organizing and mobilizing radical student groups, ensuring that normal academic activities are impossible. Their orchestrations have led to protests, encampments, intimidation, harassment, seizure of U buildings, and disruptions of UMN commencement ceremonies and President Cunningham’s inauguration. Hillel has been a specific target: it has been shot at, Jewish students have faced physical threats, and attendees at a Hillel events were once forced to shelter in place under police protection.

The measurable impact of FJP on campus has been documented by the Amichai Initiative:

1. Violence and threats: Campuses with FJP chapters experience a 7.3-fold increase in the likelihood of physical assaults on Jewish students and are 3.4 times more likely to witness death threats or other violent threats compared to campuses without FJP chapters.

2. Prolonged disruptions: Faculty affiliated with FJP have been implicated in extending protests, which last 2.5 times longer on campuses with an FJP presence. Encampments, when they occur, last 4.7 times longer at these campuses.

3. Sustained anti-Israel activism: Faculty on campuses with FJP chapters engage in 9.5 times more days of anti-Israel protest activities than their counterparts on campuses without FJP chapters.

FJP hides behind “academic freedom,” but their true goal is clear: to spread their extremist, pro-Palestinian, terror-enabling agenda by any means necessary. In a normal academic environment, one could trust scholars to employ reason and self-discipline, but these are dangerous times. FJP’s bottom line is not academic inquiry; it is Jew hatred and Israel hatred, cloaked in the guise of intellectual discourse.

Sam H

Mar 19, 2025 at 11:52 am

Excellent read, Hannah, excellent reporting.

change it up

Mar 19, 2025 at 9:47 am

Are you unsatisfied with the current batch of Regents?

Take heart and take action!

Four Regents – Mayeron, Kenyanya, and Davenport, who voted in support of the resolution, and Thao-Urabe who voted no – are almost at the end of their terms and are not running for reappointment.

The U of Mn Alumni Association Regent Candidate Guide 2025 has a list of current candidates (spoiler alert: ex-Interim President Jeffrey Ettinger is on the list) as well as other important information about how Regents get appointed. The initial interviews and candidate forum livestreams are also available in various places on Capitol YouTube channels.

If you have an opinion on who you would prefer to (not) see as UMN Regent, do as much research as you can, then contact your legislators to let them know which candidates you want them to support.

Stop whining

Mar 19, 2025 at 9:01 am

Doesn’t this all boil down to deciding who speaks on behalf of the University? Divisive departmental statements on controversial social issues should not be allowed on official University platforms. There are plenty of other ways to voice their opinions. The UMN President has the authority to speak on behalf of the University, as confirmed by the Board of Regents. This resolution has nothing to do with academic freedom or free speech.

BRUNO CHAOUAT

Mar 19, 2025 at 7:49 am

It is disingenuous to complain about censorship when one calls for censoring and boycotting scholars based on their national origin. GWSS and CSCL call for the boycott of Israeli academics. At the very least they could have the decency to remove this call from their unit statements.