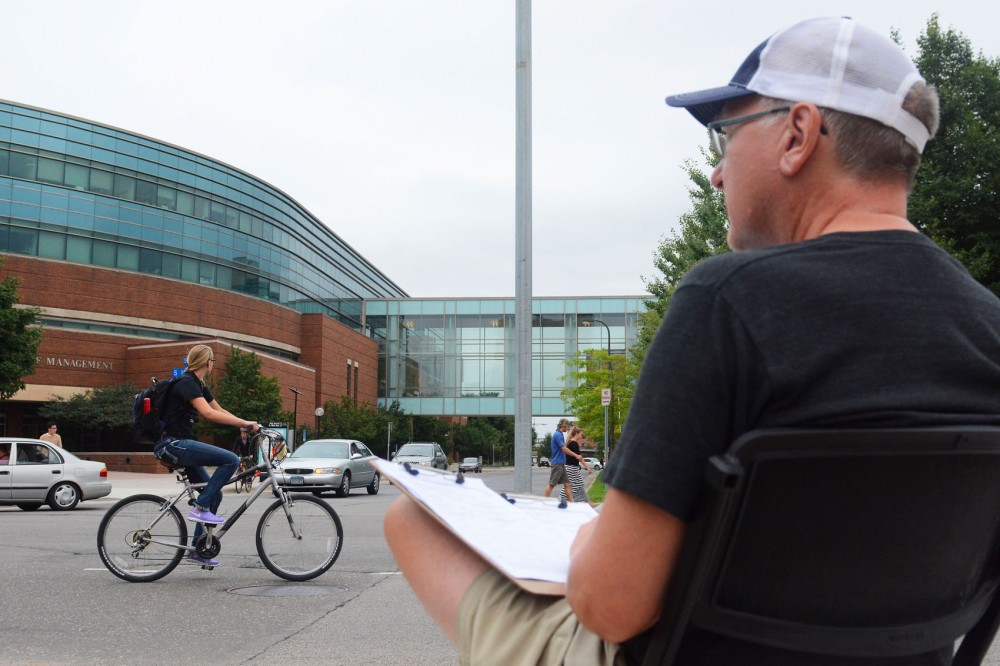

Standing on the corner of Cedar and Riverside avenues Tuesday afternoon, Jacob Knight stared intently at each passing bicyclist and pedestrian.

As each one passed, he checked them off, remaining largely unnoticed by the world around him.

The urban and regional planning master’s student was volunteering for Minneapolis’ annual survey to see how many of its citizens walk and bike.

Since 2007, the city has monitored bicyclists at 30 main locations, with intersections near the University of Minnesota reporting consistently high counts. The method helps transportation officials monitor and plan bicycling initiatives based on traffic patterns, and bike traffic citywide has spiked in recent years.

City staff members and about 100 volunteers will complete their three-day count Thursday, tallying bicyclists and pedestrians in small time increments over the course of two hours, said Simon Blenski, a Public Works Department bicycle planner.

The Washington Avenue Bridge and two spots in the Dinkytown area have ranked among the top five most frequented bicycle locations since 2011.

Citywide, an 11 percent increase in bicycle traffic between 2012 and 2013 followed a cumulative 56 percent increase in the five years before.

This year, Blenski said the city doesn’t expect an increase in bicyclists that exceeds 10 percent.

“I would expect it to keep pace,” he said.

To conduct the study, volunteers sign up and complete a short, online training course that prepares them to count and tally every passing bicycle by hand, Blenski said.

“It’s a lot to organize, but we’ve found a pretty streamlined way to do it,” he said.

Knight said he decided to volunteer because he wanted to help create valuable data to inform city planning.

Dave Paulson, a city volunteer who bikes to work daily, said he thought counting bicycles would be a good way to contribute to new bicycle infrastructure.

“I think [bicyclists are] an underserved population in the city,” he said.

Minneapolis has a few automated locations to count passing bicycles, Blenski said, but they are expensive, require calibration and aren’t completely accurate. Using volunteers and staff members to supervise has provided consistent results, he said.

Keeping track of bicyclist numbers helps the city evaluate the success of its infrastructure goals and plan new ones, like bike trails and green-painted bike lanes, he said.

“All those goals are tied to hard data,” Blenski said, adding that bicycle infrastructure helps the city become more sustainable.

Minneapolis officials watch for traffic changes after implementing a bike lane, Blenski said — like increased bicyclists and fewer bicycles riding on the sidewalk — so they can make adjustments in the future.

Anecdotal evidence shows students are reaping the benefits.

Noah Wilson, president of the University’s Cycling Team, said he doesn’t have a problem getting around campus on his bike.

“From my experience, cycling is pretty popular on campus, and I would say fairly accessible as well,” he said.

Grant Flick, the team’s vice president, said he’s excited to see the types of bike paths the city will implement in response to the survey.

“It all comes down to infrastructure,” he said.

Despite the accumulation of seven years of bike traffic counts, Blenski said experts sometimes cannot make definitive conclusions for up to several years.

“We would like to think that [the biking increase is] primarily due to infrastructure investments,” Blenski said.

In order to continue promoting increased bicycle use around Minneapolis and the University, the city works to create connections with the campus, he said.

The University will conduct its own bicycle and pedestrian traffic counts for the East Bank, West Bank and St. Paul campuses later this month, said Jacqueline Brudlos, communications manager for Parking and Transportation Services.