Students enrolled in Professor Gilbert RodmanâÄôs communication studies class are shocked to find they will have to bring a yoga mat or recite the âÄúPolka PledgeâÄù each class meeting.

His syllabus for New Telecommunication Media is designed with a set of rules âÄî some ridiculous, like requiring students to correctly predict a week of National Football League game outcomes âÄî and some rules expected in an average University of Minnesota classroom. Students spend the semester voting out the ridiculous rules and voting in new ones, changing the syllabus as the semester progresses.

Rodman is in his eighth semester of teaching with what he called the âÄúhackableâÄù syllabus, which he changes slightly for each class.

The students are meant to take control of their education and change the syllabus so it works for them, Rodman said.

The âÄúbad rules,âÄù as Rodman calls them, are rules which are completely unrelated to the class and will not benefit the students.

This semester the students have successfully voted out all the âÄúbad rulesâÄù that were initially in the syllabus, Rodman said. They have only made a couple of small changes to the class otherwise.

âÄúMany students are trained to sit down, shut up and do what theyâÄôre told,âÄù Rodman said.

He said this class is built to engage students in an âÄúun-learningâÄù of this education style.

Edward Schiappa, chair of the Communication Studies Department, said in an email that faculty members are allowed to be as creative as they want with their syllabi, as long as it is consistent with University policies.

âÄúI have seen syllabi (including my own) over the years that allow students to customize certain aspects of the course to meet their needs, such as allowing them apportion how much of their grade is based on certain elements,âÄù Schiappa wrote.

âÄúNot all rules or elements of the course are up for grabs, in Professor Rodman’s or anyone else’s course,âÄù he added.

RodmanâÄôs fall 2011 syllabus has 10 permanent rules outlining basic procedure for changing rules and the course requirements that canâÄôt be changed.

Course assignments, readings and grading are in a second category of rules that can be repealed or amended with a two-thirds vote.

âÄúIn theory, the class could change assignments and readings, but no one has,âÄù Rodman said.

He said that many classes stop changing rules after the bad rules are voted out.

Joe Klimek, a communication studies senior, said changing the rules is the most frustrating part of the class because of the time it takes to write a proposal and get the class to vote.

Klimek said the semester is too far along now to keep making changes. He said heâÄôd rather focus on what needs to get done.

But RodmanâÄôs unique approach isnâÄôt limited to his syllabus.

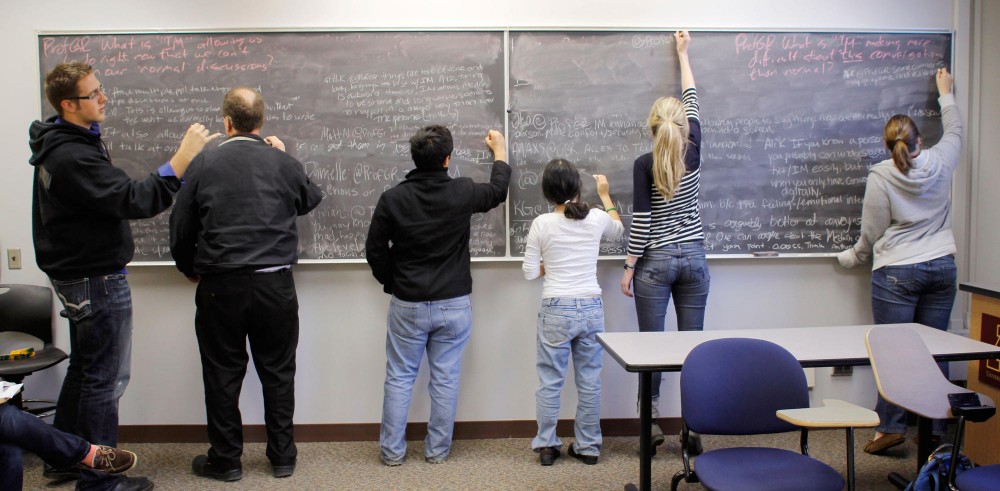

Sitting in a circle, students and the professor quietly approached the chalkboard to âÄúvoiceâÄù their thoughts on the assigned readings about what instant messaging brings or takes away from conversation as well as how people use it.

Rodman approached the chalkboard and wrote a question. When the students asked a question or made a comment, he silently pointed to the board, encouraging the class to write their thoughts instead of verbalizing them.

As students caught on to the activity, the board quickly filled up with ideas. Rodman wrote questions and comments, and students responded, sometimes having as many as six people writing on the board at a time.

Rodman introduced the new activity to illustrate the differences between verbal and written communication to relate it to their readings about instant messaging.

The group carried on the discussion for nearly an hour. Afterward, they assessed how it affected their ability to communicate.

The class had mixed feelings about the concept.

The activity is âÄúa good way to be engaged in the readings and pay attention,âÄù Kaitlyn Grabinksi said.

She said she walked away from the activity with the idea that verbalizing is more efficient because writing and waiting took a long time.

Tara Turch, another student in the class, said writing on the board âÄî similar to instant messaging âÄî allowed for multiple people to carry on different conversations at once.

Other students argued the activity did not allow them to go as in-depth as they would have in a normal class session. Some thought it was beneficial because no one had to wait to talk.

While the syllabus and class exercise are interesting, some students think they might act as too much of a distraction.

âÄúPart of me thinks we should just learn what we need to learn, but I can see what Professor Rodman is trying to do by making us vote,âÄù Klimek said.