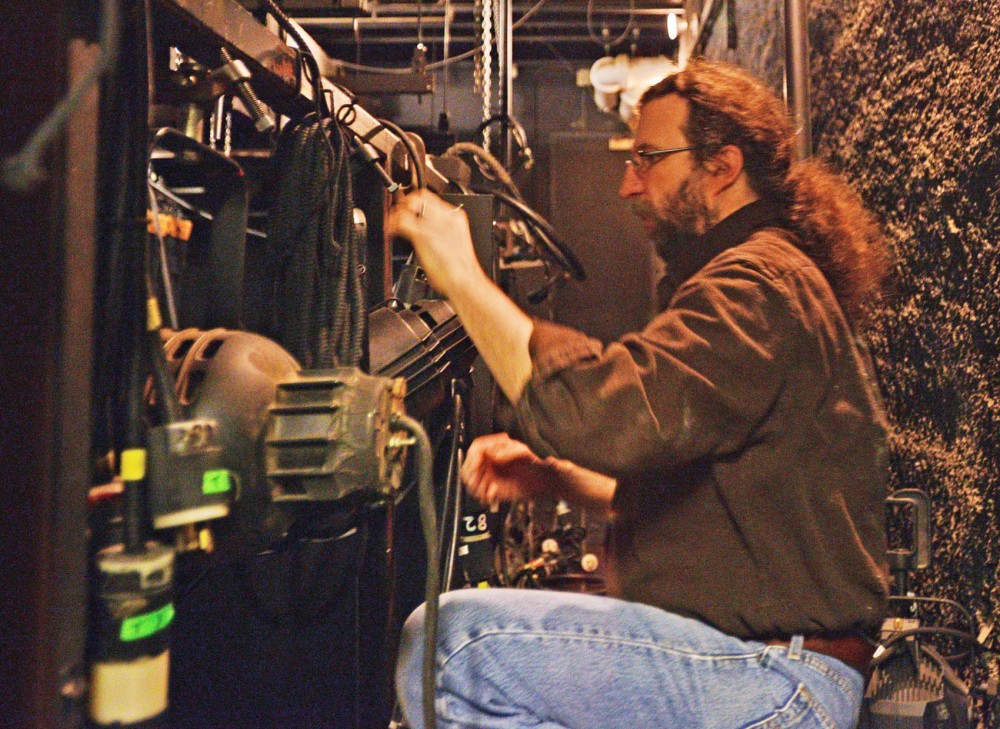

Mike Kittel is responsible for one of Park Square Theatre’s most important visual components in live performance — and the stealthiest.

“Every light that we put on stage is helping illuminate performance, the sets and other designs,” said Kittel, the resident lighting designer. “We have a great responsibility to reinforce other people’s work.”

Although stellar design is crucial to a great show, designers remain unsung heroes. Kittel said as far as theater lighting is concerned, the less an audience notices what’s going on around the catwalk above them, the better.

A designer’s goal isn’t about what an audience sees. It’s about making them feel something. For example, Kittel said, people don’t just see blue lights over the stage with some stars. They feel the sense of “nighttime” and all its connotations.

Marcus Dilliard, award-winning designer and University professor, said his own idea of “feel” plays a huge part in his creations.

“What we do is similar to what a cameraman and an editor do in film,” he said. “We control what the audience should be looking at.”

About a week and a half before a play opens, there are usually a few days set aside for technical rehearsals. A technical rehearsal is precisely what it sounds like — lights, sound and all of the final design elements come into play.

For lighting designers, this is when their work is put to the test. Dilliard said that he doesn’t specifically plan his designs ahead of time anymore.

“I just like to respond to what’s there,” he said. “A lot of my work happens when we’re in the theater.”

Frankly, Dilliard said, there’s no way to know what’s going to work before getting everyone in the same room. Without knowing variables like how people are going to move on the stage and how a certain light will affect their costume, a lighting designer has to think quickly to be worth their salt in a professional production.

“If you can’t deal with time or transitions as a lighting designer, you’re not doing your job,” Dilliard said. “A lot of people can make pretty pictures with light but many can’t make their way from one picture to another.”

The lighting, in a sense, is another performer onstage. Jesse Cogswell, a recent graduate of the University’s MFA program in lighting design and technology, learned this by stepping out of his theater comfort zone.

He’s been designing for Ballet Works with the James Sewell Ballet at the Cowles Center and discovering the big differences between styles. Instead of surreptitiously slipping his design into the scene, he found that dance asked for a vibrant and easily noticeable approach.

“I would go see shows and when something worked really well, I would look up,” he said. “I wanted to know how they did it.”

Each of these designers said they like to light things outside of straight theater — mostly because of the challenge, but also because these other projects allow larger gestures with their work.

“I love musicals, in general. Good ones. They’re fun to light because you get to play around more and leave realism,” Kittel said.

Having lit more than 100 shows at Park Square Theatre, Kittel said he appreciates shows that make him rethink the environment he knows so well. He’s had to light shows with roofs partly over the stage, time out cues that perfectly replicate a sunset — he sat in his backyard and watched how the colors in the sky changed until it was completely dark — and improvise.

These challenges could be migraine-inducing, but they’re what attract those who choose the design route.

“Every show is a problem,” Kittel said. “There’s no correct answer to them. You have to put your stamp on it and figure out a way to make it work.”