A recent research breakthrough may have discovered the main culprit behind a worldwide disappearance of bees, placing the blame of a type of insecticide.

More than 1 million people have signed a petition to ban neonicotinoids produced by Bayer CropScience — a leading pesticide producer — which are suspected to cause Colony Collapse Disorder in bees.

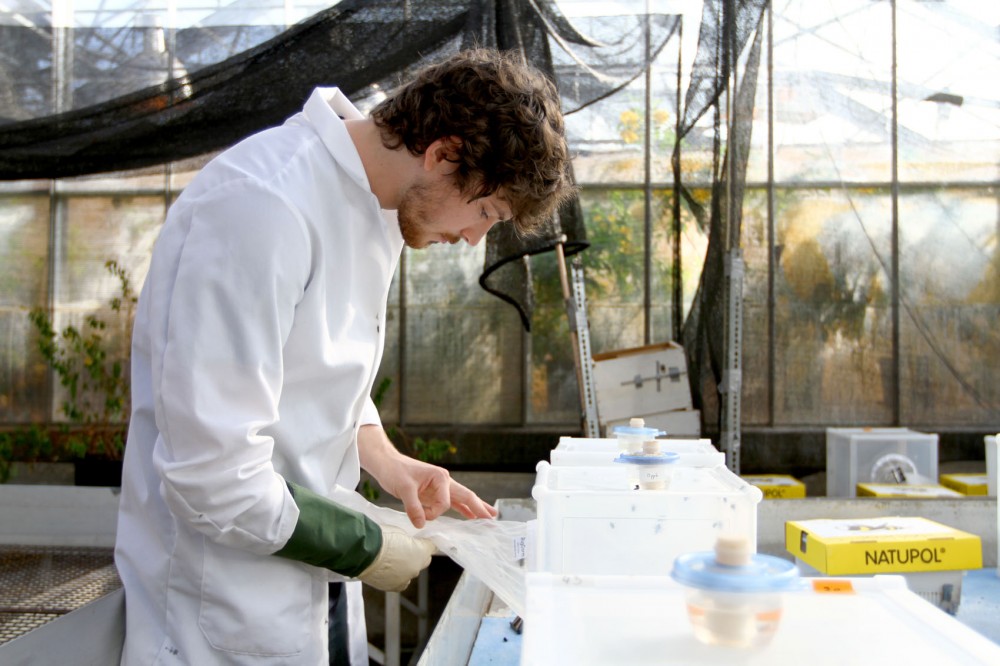

But University of Minnesota researchers who have studied the effects of neonicotinoids for years say more research is needed before the Environmental Protection Agency approves such a ban.

Bee pollination of agricultural crops, like fruits, vegetables and field crops, accounts for about a third of the U.S. diet, according to the petition.

CCD is marked by the disappearance of bees from the hive, often leading to the collapse of the colony. Since more than a third of produced food needs pollinators like bees, it has been a hot topic for the beekeeping community, said Judy Wu, a graduate student who researches neonicotinoids at the University’s Bee Lab.

“There’s a lot of different research saying a lot of different things, and I think that’s not enough evidence for the EPA to ban a particular class,” Wu said.

Proponents of the EPA petition, however, hold that neonicotinoids are the main cause of CCD.

Neonicotinoids are among the few systemic insecticides, meaning they get into every part of the plant, which is why they can be a problem for bees — they can get into the pollen.

Ninety percent of the agricultural industry in the U.S. uses seed treatments to genetically modify crops with pesticides before they are planted, said Vera Krischik, an entomology professor who researches neonicotinoids at the Bee Lab.

These pesticides become part of the genetic makeup of the plant, protecting them from damage. But plants genetically modified with neonicotinoid pesticides do not have high enough trace levels to kill a bee, Krischik said.

She said bees are fighting off many other things like pathogens, parasites and human interference.

“There’s so many contributing factors to CCD that it’s hard to tell if it is neonicotinoids or it’s something else,” said Gary Reuter, a head scientist at the Bee Lab.

Researchers studying pesticides at the Bee Lab are specifically looking at the effects of high doses of neonicotinoids, which are used in landscaping and in controlling invasive species like the Emerald Ash Borer.

The lab found that high doses of neonicotinoids did kill bees, with more than 300 mg per plant killing a significant number.

“I have the data to say, ‘Yes, this is an issue and we need to talk about it,’” Krischik said.

But she and other Bee Lab researchers are more concerned about the EPA’s regulation system.

The EPA relies on pesticide companies’ research for registering pesticides and only validates the research after the product has been approved.

Because this system is in place, Krischik said she wasn’t surprised that it has taken this long for independent labs to find the negative effects of neonicotinoids.

“Labs like ours can’t get the money to do research because grant companies don’t think pesticides are an issue,” she said.

That’s why many researchers believe that the EPA’s regulation system needs an overhaul.

“What I do think is a positive thing is beekeepers speaking out and showing their concern,” Wu said. “I think it shows that there needs to be a re-evaluation of our whole regulation of pesticides.”

But even with a majority of beekeepers uniting against neonicotinoids, Reuter said a full ban by the EPA is unlikely.

“A complete ban would be beautiful,” he said, “but one has to work within realities.”