For just about everyone paying attention, the passage of the national health care legislation inspired more questions than answers. The bills that are now law âÄî a 2,309-page reconciliation bill on top of the 2,074-page Senate bill âÄî are merely framework and will mean a lot more when implemented around the country. For University of Minnesota students, the changes have several implications. Although theyâÄôll be required to have insurance, students will get help doing so and could even be eligible for state assistance programs. Students covered under their parentsâÄô plan will get to stay on until theyâÄôre 26. If thereâÄôs one thing MinnesotaâÄôs policy experts agree on, itâÄôs that the legislation is merely a starting point to the larger process of reforming the nationâÄôs health care system. âÄúHealth care reform isnâÄôt done, itâÄôs just that this is a big first step,âÄù said Eileen Smith, spokeswoman for the Minnesota Council of Health Plans. âÄúThereâÄôs a lot of work left for all of us to do.âÄù Some argue that the legislation doesnâÄôt offer enough guidance or clarity on financing the changes. After mulling over the billâÄôs complex language, Roger Feldman, University health policy and management professor, said heâÄôs not sure how it will all play out. âÄúThe bill lacks a plausible financing mechanism,âÄù said Feldman, a consultant to the Congressional Budget Office. âÄúIâÄôm afraid that instead of reducing the deficit by $140 billion over the next 10 years, itâÄôs actually going to increase the deficit.âÄù Despite the claim that the reform will save money, Ed Ehlinger, director of Boynton Health Service, said it contains few cost-containing or quality improvement measures. âÄúI just hope that this is a first step in an ongoing approach to health care reform,âÄù he said. âÄúI hope this isnâÄôt the end, because lots of problems are going to surface from all of this.âÄù The mandate The most obvious and sweeping change comes in the form of a nationwide insurance mandate. Starting in 2014, itâÄôs pay for insurance or pay a fine. That means big changes for the nearly 15 percent of students on the UniversityâÄôs Twin Cities campus who are uninsured, according to a 2007 Boynton Health Service survey. All told, 22 percent of MinnesotaâÄôs 18- to 24-year-olds were uninsured in 2009. Luckily, those between 133 and 400 percent of the federal poverty level will get a leg up to pay for insurance based on their income. For example, a college graduate making $32,490 per year is at 300 percent of 2009âÄôs poverty level ($10,830), meaning they would not pay more than 9.5 percent of their income, or $277 per month. Those without insurance will have to pay a penalty of 1 percent of their income in 2014, 2 percent in 2015 and 2.5 percent in 2016. Exceptions to the mandate include undocumented immigrants, American Indians, those in prison and those with certain religious objections. People will also be excused if the cheapest plan is still more than 8 percent of their income or if their income is below the tax filing threshold, which was $9,350 for an individual in 2009. Better coverage, longer An item thatâÄôs won approval from young people requires insurers to cover dependants âÄî regardless of student status âÄî until age 26, effective in six months. Since 2008, however, Minnesota law has required a significant portion of its privately insured plans to cover dependants until age 25. These plans, called âÄúfully insured,âÄù are group or employer plans that covered 27 percent of the privately insured in 2007. Although confusion has surrounded the billâÄôs impact on the more than 40 percent of privately insured Minnesotans covered under âÄúself-insuredâÄù plans, Nick Papas, spokesman for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, said it applies to all private plans, no exceptions. âÄúItâÄôs not an option,âÄù he said. Representatives from insurance giants like BlueCross BlueShield, Medica and HealthPartners âÄî up to 70 percent of whose policyholders are self-insured âÄî say language in the bill makes it unclear whether this area, which is traditionally exempt from state regulations, is included. Self-insured plans allow large employers like General Mills and 3M to shoulder the risk by paying employeesâÄô medical costs and hiring an insurance company to manage the policies. Many of the plans cut off dependants between ages 18 and 21 but will now be required to cover them until age 26 âÄî a costly change for providers. The bill also eliminates that infamous dealbreaker in 2014: the preexisting clause. Currently, MinnesotaâÄôs largest insurers include preexisting condition exclusions on their major plans. âÄúThatâÄôs a standard in the industry,âÄù Medica spokesperson Larry Bussey said. Insurance companies also wonâÄôt be able to impose lifetime restrictions on their plans. Businesses with more than 50 employees will need to offer health insurance or pay a per-employee fine. Feldman said he fears this stipulation will tempt businesses that employ low-wage workers to opt for the fine rather than covering their employees. He said he also worries it will encourage businesses to hire fewer than 50 employees. Medicaid multiplied The new legislation promises to dramatically change the way Americans view Medicaid, and the program could get a lot more attention from young, poor adults once the changes kick in. The program, which has historically restricted its coverage to women with children, will cover everyone under 65 with incomes up to 133 percent of the federal poverty level beginning in 2014. That means any single adult making less than $14,440 per year would qualify for Medicaid, according to 2009âÄôs poverty guidelines. âÄúI think there will be a cultural change in the way we view Medicaid,âÄù Feldman said. âÄúIt used to be a welfare plan for mothers and children, and itâÄôs now going to be a welfare program for all low-income individuals. Medicaid is really, finally and completely breaking the link.âÄù MinnesotaâÄôs Medicaid equivalent is primarily state-funded programs like Medical Assistance and MinnesotaCare. Under the new legislation, the federal government will reimburse states for 100 percent of the newly eligible until 2017, down to 90 percent in 2020 and each subsequent year. The problem lies in the fact that more than 18 percent of Minnesotans who have been eligible for such programs have chosen not to apply for them, Lynn Blewett, assistant professor in the School of Public Health, said. This means that although thousands more are likely to join the programs, the state will only get reimbursed for the newly eligible, which will be a much smaller number. An initiative in the bill that provides federal funding for states to implement low-income, adults-only programs may have covered the General Assistance Medical Care population, Blewett said. But the newly approved reductions to GAMC make it unlikely to qualify. State legislators may try to reverse the GAMC decision âÄî in which program recipientsâÄô care is managed largely by hospitals âÄî to reap the benefit of the federal legislation. âÄúTechnically they could,âÄù Blewett said, âÄúbut I think itâÄôs probably a slim chance that it would happen.âÄù Insurance.com Running on the age-old assumption that competition drives down prices, online databases will start up in 2014, allowing health plans to be compared side-by-side. Insurance companies will have to post detailed information about their individual and group plans âÄî in a uniform fashion outlined in the bill âÄî on state-run insurance exchanges. The plans will be divided into Bronze, Silver, Gold, Platinum or Catastrophic based on their prices and level of benefits. A Bronze plan, for example, is the bare minimum, covering 60 percent of benefits and carrying an out-of-pocket maximum of $5,950 for an individual. A Platinum plan covers 90 percent of benefits. In the future, plans will likely be advertised according to their metal, Feldman said. âÄúI donâÄôt see how it could be a bad thing,âÄù he said, âÄúI wouldnâÄôt count on it to save a whole lot of money, though.âÄù The Congressional Budget Office estimates that individual premiums will increase by 10 percent to 13 percent by 2016 under the new law, but that the increase will be offset by subsidies for about half of all enrollees. Although the exchanges will be subject to more oversight than before, Ehlinger said he doesnâÄôt expect premiums to go down until insurance companies reduce administrative overhead and marketing costs. âÄúUnless those go away, the prices wonâÄôt go down.âÄù What students are saying University students expressed a range of emotions regarding the health care bill. Health care administration graduate student David Henriksen said heâÄôs afraid the changes will put a lot more strain on hospitals and primary care physicians. âÄúTheyâÄôre going to have a lot more to do and less to do it with,âÄù he said. âÄúItâÄôs going to be up to the delivery system to make this bill work.âÄù The legislation provides little guidance on how to finance the changes, Henriksen, an officer in the Institute of Healthcare Improvement, said. âÄúThey left it open,âÄù he said. âÄúKind of like, âÄòThis is what we want to do, you guys find a way to make it work.âÄôâÄù Through her job at the Hennepin County Medical Center, biology senior Rachel Weigert sees firsthand the number of uninsured who wait until the last minute to see a doctor. âÄúIf more people have health insurance or have access, theyâÄôll be able to see a doctor instead of waiting for a crisis situation,âÄù she said. Michelle Holman, a pre-med senior, said sheâÄôs disappointed the bill doesnâÄôt do more to discourage unnecessary testing that drives up costs, such as MRIs, CAT scans and blood tests. âÄúIn other countries, doctors do it if itâÄôs more necessary,âÄù she said. The bill doesnâÄôt address the issue of covering 30 million more people, so payment reform will have to be the next step on the health care totem pole, Henriksen said. âÄúI donâÄôt have a better alternative for it,âÄù he said. âÄúNobody does.âÄù

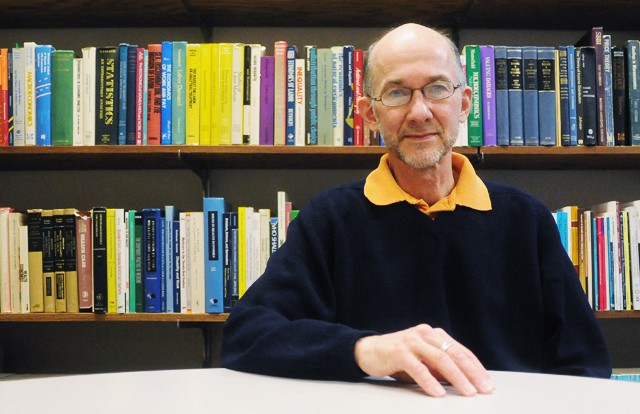

University of Minnesota health policy and management professor Roger Feldman is a consultant to the Congressional Budget Office.

Health care reform: What you need to know

The new legislation fas special implications for college students.

by Tara Bannow

Published March 30, 2010

0

More to Discover