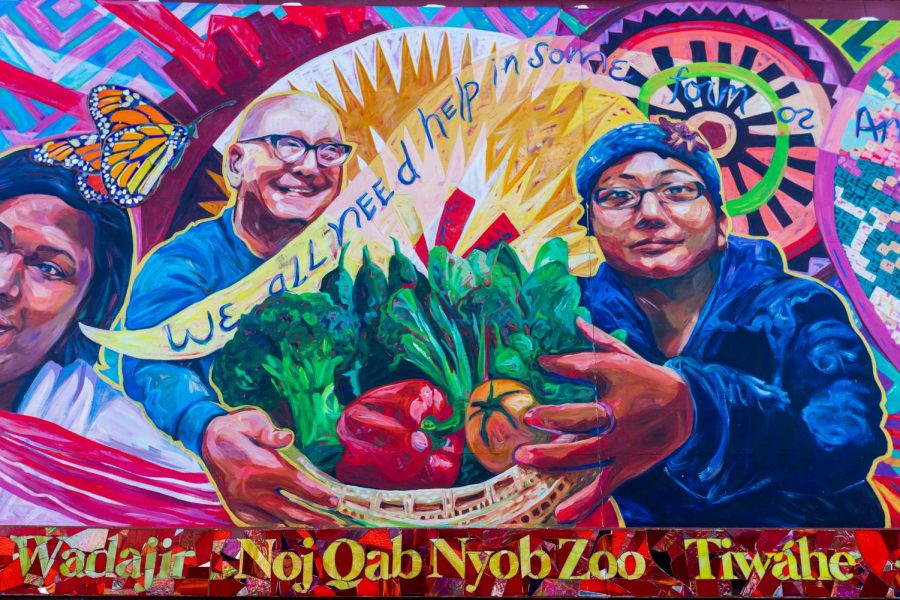

During the pandemic, the Community-University Health Care Center (CUHCC) has been doing what it has historically done: adapting to fit the changing needs of its surrounding communities in the Phillips neighborhood.

When the University of Minnesota founded CUHCC in 1966, it became the first community health center in Minnesota, providing health care to children from low-income families in the Phillips neighborhood where it is located.

Over the years, CUHCC has evolved into a clinic that provides healthcare that centers patients and their needs. In addition to offering physical and mental health services, the clinic provides domestic violence services, as well as free legal counsel. University students in medical fields can also train at the clinic to serve marginalized communities.

CUHCC implemented new efforts during the pandemic to adhere to COVID-19 safety guidelines, helped distribute food and provided COVID-19 testing at different locations, like public housing.

Sara Bolnick, director of advancement at CUHCC, has served at the clinic for the past seven years. She said the clinic is constantly changing and morphing to address the changing needs of its surrounding community.

As more American Indians came to the Phillips neighborhood in the 1970s, the clinic employed community health workers who represented American Indian tribes. Later in the ‘80s, the neighborhood continued to change with a wave of immigrants coming from Southeast Asia. During this time, a Hmong woman established one of the first advocacy services at CUHCC to address domestic abuse and sexual violence for members of the Hmong community in the Phillips neighborhood and Twin Cities.

“Being abused can be really isolating, … and seeing that you have a victim advocate and a lawyer on your side fighting for you in court is a big comfort to the clients,” said Maddie Mouanoutoua, a CUHCC victim advocate.

When East African immigrants, including Somali, Oromo and Ethopian communities, settled in the surrounding neighborhoods in the ’90s, CUHCC expanded mental health services to address the trauma of those who fled war and devastation.

In the early 2000s, Latino immigrants, primarily from Mexico, Ecuador and Venezuela, began to settle in the Phillips neighborhood. Currently, the highest population served at the clinic is Black American.

To reflect the clinic’s patient-centered mission, as a federally qualified health care center, the clinic’s board is majority patient-led.

When the pandemic hit, the clinic worked to modify the space to accommodate for social distancing and make sure patients and staff felt safe, according to Bolnick. CUHCC held COVID-19 screenings and testing outside of the clinic, and patients waited in different areas of the clinic based on their symptoms.

“We quickly restructured our entire clinic and care delivery model yet again,” Bolnick said. “In a sense, we are pretty prepared, I think, to really successfully adapt to the changes COVID has brought.”

Mary Clare Baldus, program manager for adult case management and advocacy program, has worked at CUHCC for more than 28 years. She said her clients who were already anxious experienced heightened anxiety due to the pandemic.

Between March and April, Bolnick said, “It was just all hands on deck.” She added that the clinic had limited personal protective equipment and few COVID-19 testing kits for several weeks. To create more space for social distancing, the clinic turned its large meeting room into a second waiting room.

The clinic started telehealth visits and services for patients, mostly through phone call appointments. Baldus said many clients were relieved not to be asked to come in person for legal or medical services, but some patients either faced barriers accessing the necessary technology for telehealth services or were unfamiliar with the technology.

From June to August, CUHCC partnered with community organizations and clinics to start COVID-19 testing at different locations, such as The Cedars, a Minneapolis housing high-rise, home to many residents who come from low-income or immigrant backgrounds.

“We really wanted to bring the spirit of our clinic outside of the walls,” Bolnick said. “That’s what we’re hoping to do in an ongoing way, even once COVID is done. I think this is really what we’re hoping to build off of in the lessons that we’re learning from this time.”