While putting together music for his second Master’s recital in 2019, University of Minnesota alum Jared Miller said finding music by Latinx or Spanish composers was difficult, even impossible at times. “Latinx” is a gender-neutral term for Latino.

Set on finding a particular piece written by his favorite Mexican composer, Miller said he could not find sheet music anywhere, despite scouring the University’s collection, the internet and a number of other libraries.

He later found the score was only published in Cuba, and after some detective work by University music librarian Jessica Abbazio, the two eventually secured a copy from an Oklahoma cellist who had performed the piece for an heir of the composer 30 years prior.

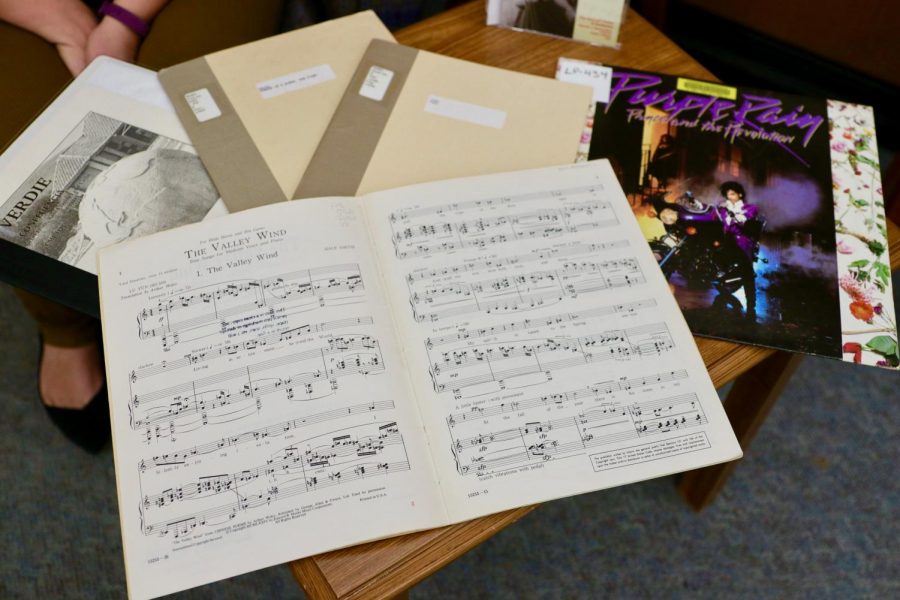

Since then, Abbazio has made it her mission to diversify the University’s Music Library, an immense task but one she has taken to heart. The physical collection houses over 100,000 items, including music scores, recordings, books and CDs. Abbazio estimates 85% of the collection is from a white or European repertoire.

“There really has been this myth that these Western canon composers are the ultimate musicians,” Abbazio said. “And not taking anything away from them — but by setting up this, like, hall of master works, it’s kind of a closed loop … There’s a bubble of classical music that I really think needs to either expand or burst.”

Curricula focused on the Western canon

Miller said throughout his career, classic music education has centered Western artists like Beethoven or Mozart, who are seen as the “standard” music students should learn and play. This by association often equates African, Asian, Latinx or Spanish music as “lesser,” especially if the music was derived from folk traditions, he said.

Growing up, he remembers choir directors choosing to add a Spanish piece to their program as a way to “add a little spice” or “because it’s fun, or it’s different” rather than study or appreciate the musicality of the piece in the same way they did other songs they studied. While a student at St. Olaf College, two semesters of his vocal literature class were dedicated to learning English, German, Italian and French songs. Only one day was spent learning songs in Spanish.

“Since high school and onward it’s been frustrating for me, and I’m sure it has been for my other Latin American musician friends,” he said. “Because I did not grow up knowing that Latin America had classical music.”

Because many music schools focus primarily on producing classically-trained musicians who perform in an orchestral setting, students are taught about predominantly European composers, said Anne Briggs, a second-year Ph.D student in the University’s ethnomusicology department.

Briggs said Abbazio’s work will give teaching assistants like her the resources to show students an “unimaginable breadth of music performance” they would typically not get from their standard textbooks.

“What’s particularly exciting about [these] efforts … is representation,” Briggs said. “Without an attention towards what’s missing, who’s being left out of the conversation, what are we not including in our library catalog— sometimes you don’t even know it exists.”

Lasting impact

Abbazio said this work is crucial for an institution like the University of Minnesota, whose collections are available to not only the whole student body, but also others in the community who can access the — often expensive — materials through interlibrary loans.

Moving forward, Miller said he would like to see change come from teachers as well. Not only does he want to see more professors utilizing the Music Library’s resources, there needs to be a change in the curricula to reflect a greater appreciation for a range of music and styles, he said.

“There’s something so important about venturing outside of the Western canon because, for me, it helped me discover and explore my own personal and cultural identity,” he said. “I know that sometimes, to no fault of their own, teachers are hesitant to [teach outside of their comfort zones], because they themselves don’t know about it. But that’s an opportunity for growth for them as well as their students.”