After two evictions, organizers and City Council members are advocating for change at the unhoused encampment Camp Nenookaasi in support of the residents despite opposition from Mayor Jacob Frey’s office.

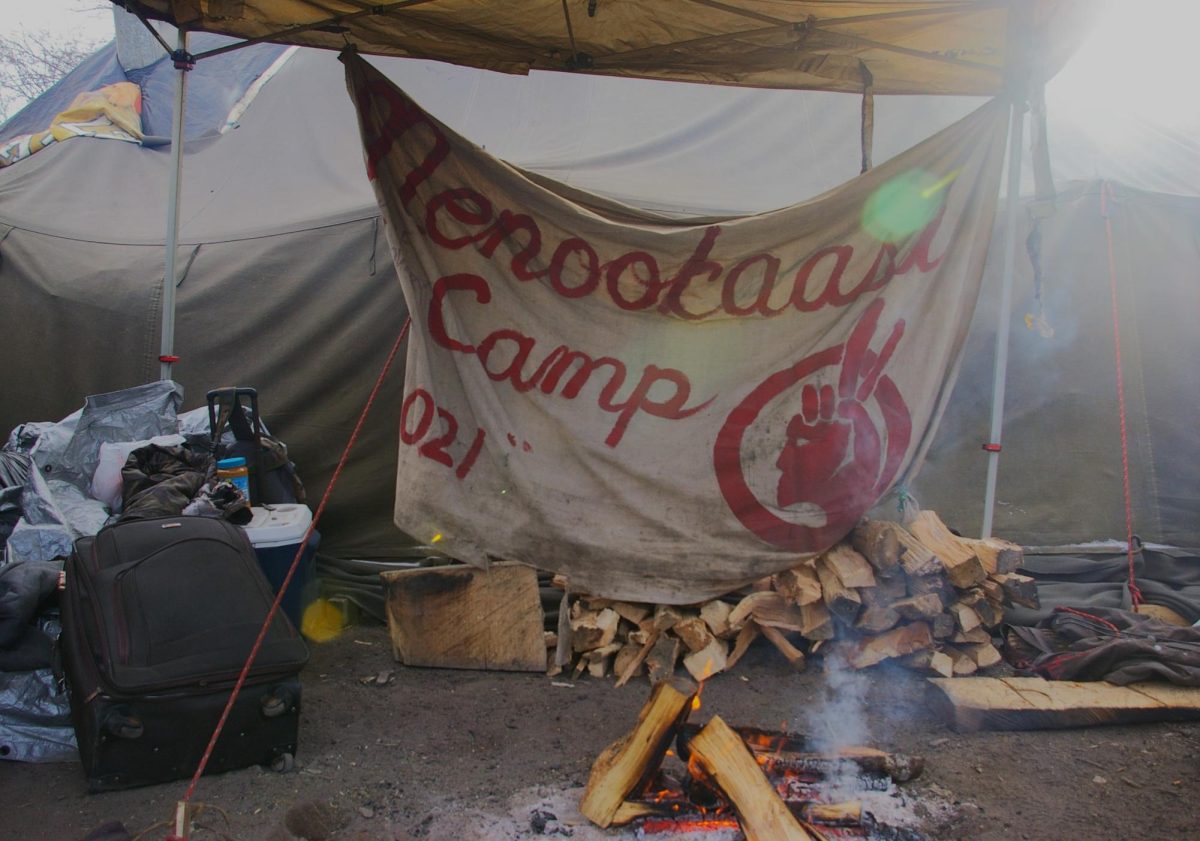

Established in August of 2023 on the corner of 13th Ave. South and 23rd St. East in the East Phillips neighborhood, Camp Nenookaasi houses about 150 people, many of whom are indigenous. The encampment provides a space to live, a communal kitchen, a prayer fire and a community for unhoused people in the Minneapolis area.

The city initially planned to evict the camp on Dec. 14 after a fatal shooting took place there in December and the spread of illness. The eviction was delayed as the camp worked to find housing accommodations for its residents.

Camp Nenookaasi is now located at 14th Ave. South and 26th St. East, and camp organizers and members continue to recover from a hectic eviction.

Christin Crabtree, a Camp Nenookaasi organizer, said despite the eviction process being “really stressful and really heartbreaking,” it was easier than other evictions she and camp members have experienced.

“In many ways, [it was] a better experience than any other eviction,” Crabtree said. “They’re always traumatic, but in the sense that the police stood back, they listened to us when we were like, ‘Give us time and let us get people moved in a good way,’ as much as we could.”

The negative impacts on camp residents became more evident in the eviction aftermath, according to Nicole Mason, another Camp Nenookaasi organizer. Mason said the camp’s mood has plummeted following the move.

“I saw the trauma in people, I definitely saw the shift in camp,” Mason said. “[It’s] like they lost their survival skills or like they have no drive to do anything, the depression really kicked in the camp.”

Emotional trauma is nothing new for the unhoused who have dealt with previous evictions, mental health struggles and drug addictions, according to Crabtree and Mason.

Organizers want the city’s approach to unsheltered homelessness to change, according to Mason, who also said the city should allocate funds for evicting the unhoused into funds for support.

“Not to throw it in their face, but we have saved the city a lot of money by not evicting, so why not invest that money that was in the budget, supposedly that’s $70,000 to $250,000 per eviction? Why don’t we invest that in the people?” Mason said.

In response to the camp, the city council took two actions: they sent a letter asking Frey to delay the eviction and declared unsheltered homelessness as a public health emergency in December.

Councilmember Robin Wonsley (Ward 2) said the letter to Frey addressed a potential response plan to treat unsheltered homelessness as a public health issue by providing resources to unhoused people.

“We also submitted a letter to Mayor Frey’s office asking for a delay in the closure of Camp Nenookaasi and to work with council to create a response plan that every resident of Camp Nenookaasi would have stable housing, and also have all of the wraparound services that they need in order to lead stable lives,” Wonsley said.

Wonsley added that pushback from Frey’s office has been counterproductive to city council’s efforts to change the city’s approach to the issue.

“You will see city staff again framing our unhoused residents as predominantly criminals, that they’re harboring weapons, they’re involved in drug trafficking and all these things,” Wonsley said. “Those were not the questions that the council members who authored the legislative directive had raised.”

While city government remains at odds over how to respond to unsheltered homelessness, Crabtree said no matter what legislative action is taken, camp organizers will not relent in their support and advocacy for the unhoused.

“I’m not interested in hearing no,” Crabtree said. “Regardless of what they do, [Mason] and I, we’re not gonna abandon these people. We’re going to figure it out every time until something changes, whatever that is, and so they better get with the program.”

Crabtree said many unhoused citizens have dealt with abusive or unstable family environments, like aging out of foster care, that can lead people to end up on the street.

“I wish that people that don’t spend time here could see our residents as human beings,” Crabtree said.

According to Crabtree, meeting people’s basic needs and building safety and stability makes room for people to start healing and have the ability to make choices like seeking treatment.

“The only way I know how to make justice is to change the conditions that cause the harm and also to be a people that can hold one another after the harm,” Crabtree said.